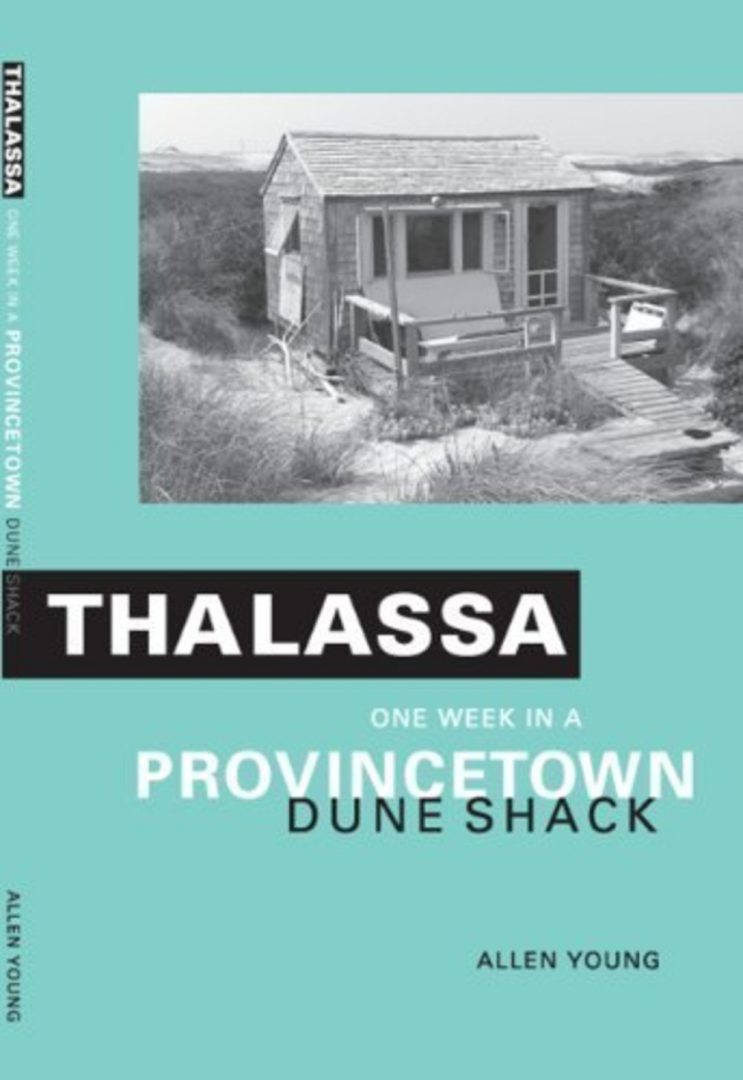

‘Thalassa: One Week in a Provincetown Dune Shack’ by Allen Young

Author: Steven F. Dansky

November 10, 2010

Allen Young is a long-time political activist who joined the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) in New York City a year after the Stonewall Rebellion. He collaborated with lesbian writer and scholar Karla Jay on four books, including the anthology Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation (NYU Press, 1992).

Thalassa: One Week in a Provincetown Dune Shack is the text of a journal Young wrote during a one-week stay in one of the historic sand-dune shacks on Cape Cod.

About nineteen wooden shacks—built in the early 19th century as survival huts for shipwrecked sailors—comprise the dune district along a three-mile stretch of the Atlantic Ocean coastline within miles from Provincetown’s main street. The sand-dune shacks are without electricity or running water, and inhabitants depend on a well and use an outhouse.

For many decades a shack culture developed that attracted a coterie of well-known artist, writer, and poet inhabitants, including e. e. cummings, Wilem de Kooning, Annie Dillard, John Dos Passos, Harry Kemp, Jack Kerouac, Norman Mailer, Boris Margo, Mary Oliver, Eugene O’Neill, Jackson Pollock, Alan Shapiro, Hazel Hawthorne Werner and Edmund Wilson, who used them as summer retreats.

Vistas of dune fields and seascapes were inspiration for painters and photographers such as Edward Hopper and Joel Meyerowitz.

Without a subtextual reading of Thalassa, the small book seems a naturist meditation on solitude—after all, Young chose to leave urbanity for Butterworth Farm, a gay-centered intentional community in the woods of rural Massachusetts where he’s lived in an octagonal house since the late 1970s. However, Young’s consciousness spun around the sexual identity-based and gay sensibility politics of the early LGBT liberation movement.

His perceptions of reality and experience originate from those political ideologies; however, this review is not the appropriate forum for a debate about concepts of identity politics or the elusive gay sensibility. Suffice to note—those formulations were integral to the LGBT movement during the 1970s.

Young derives from a tradition that defines consciousness through the lens of the gay sensibility. Consider the following passages in Thalassa: “There’s a pitcher on the table with two pink gladiolas and two yellow ones.”

The look of things, “a table with gladiolas,” progresses from outer observation to inner reality and as a qualifier of identity. Gladiolas aren’t mere flowers, but symbols of particularity and identity.

“I’m such a fag and proud (emphasis added) of it. Of course, I use the term ‘fag’ with a bit of humor, not as an anti-gay word, but to reflect a well-accepted idea about gay sensibility and the way that so many gay man appreciate flowers while for so many straight men an interest in flowers is considered unmasculine.”

Young’s contemplation on identity expands with the following passage. Personal transformation is a central tenet within the politics of identity. When Young chooses the words proud and pride, the objectivity of flowers on a table becomes a self-celebratory moment, evocative of a gay-pride slogan.

“There’s plenty of beauty here without rich showy flowers such as glads, but it adds something to the experience, and the pride (emphasis added) in having them here is also related to the fact that I grew them.”

Young’s understanding of historicity—with its collective and personal constituents—is explained in this reflection.

“What I’m experiencing at Thalassa has so little connection to P-town as a GLBT resort. . . And yet, there is a connection of sorts related to the natural beauty and light, to the aesthetic experience that drew artists to P-town early in the twentieth century. Gay men and lesbians were among those artists, bohemians, and theater people . . .”

In Thalassa, Young experiences a state of interiority, the sand-dune shack reality represents his self-perception as a gay man. Outside is a world of tangentiality, passing figures or interlopers.

He writes in the following two examples, among others in Thalassa: “Earlier today I saw a young couple (male and female) with small backpacks. I was standing at the dune edge, and they saw me. The girl waved, and I waved back.”

Or the following: “A man just walked by Thalassa and looked at me through the window. I was light seated at the table eating lunch. He quickly turned away and went down the path to the beach.”

The crescendo in Thalassa occurs with soaring Whitmanesque exuberance: “I stood naked on the beach for a while, no one in sight…. What a feeling of freedom and self-awareness!” Pure exultation and optimism.

——

Thalassa: One Week in a Provincetown Dune Shack

By Allen Young

Haley’s

978-1884540233, Paperback, 82pp.