The AIDS Crisis Revisitation

Author: Theodore Kerr

January 4, 2018

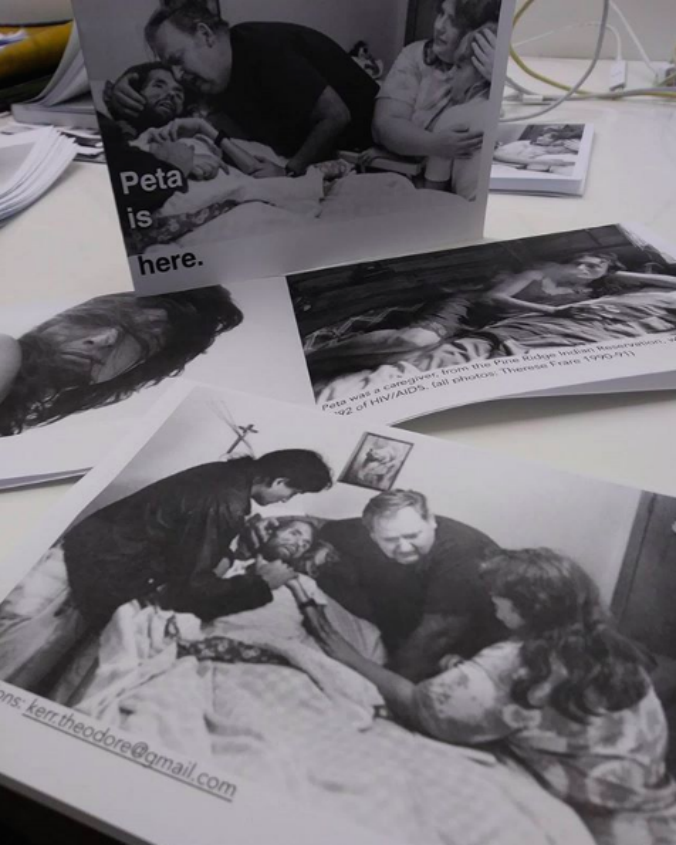

In this famous photo, on the right side, a sister’s hand cradles the top of her niece’s head, covering one ear, and drawing a shoulder close. The two look forward, eyelids soft. The niece’s left hand is on the hospital bed railing where her uncle, David Kirby, lays; his eyes open, looking out, above and beyond. David’s father swaddles his son’s head and elbow with his hands, meaty; his eyes, closed; nose, gentle against his son’s forehead. Both David and his father wear watches. Above them, a painted hand beckons forward, the rest of the body cut off by a photographer’s eye. To the left, another hand, body unseen, holds David’s wrist.

The image, “David Kirby on his deathbed, Ohio, 1990,” was taken by Therese Frare the spring that David died of complications related to AIDS. Months after, the picture was published in Life Magazine. Two years later, it was used for what became an infamous Benetton clothing ad. The photograph provides an important and familiar narrative–a frail young man, dying needlessly before his time. And in that, the picture also contains details and absences that speak to stories and dynamics of the ongoing AIDS crisis largely untold, teetering on the precipice of being lost.

The hand on David’s wrist belongs to Peta, who, the day the photo was taken, invited Therese, a photography student at the time doing a project on AIDS, to follow as Peta did rounds as caregiver at the hospice. Therese stayed in the hallway as Peta went in to check on David, a friend, who was near his final days. Therese had met David once before and he had given her his permission to be photographed. As Peta visited with David, David’s mother invited Therese into the room, asking her to take photos of what could be their last moments all together. On Therese’s contact sheets from that day, which you can view online, Peta’s whole body can be seen: tall, with long hair pulled back, wearing a black leather jacket, a comb peeking out of a back pocket of light blue jeans. In Peta, we meet a caregiver from the the Pine Ridge Indian Reserve, living with HIV, who, as Therese recalls, “rode the line between genders.” After David died, the Kirbys made a commitment to care for Peta as death approached, and Therese continued to photograph. In one image we find Peta in a wheelchair, looking down, hair in braids. David’s parents standing behind, the sheen of Peta’s silky robe midnight against the Kirbys’ matte white cotton stomachs.

Recently a short web documentary, David Kirby on his Deathbed, was made about the iconic David Kirby photo, joining the ever growing body of work looking back at HIV history. My writing partner, Alexandra Juhasz, and I call this body the “AIDS Crisis Revisitation.” Starting after a period of AIDS-related silence emerging after the release of life-saving medication in 1996, the AIDS Crisis Revisitation begins in 2008 with a noticeable increase in the creation, dissemination, and discussion of culture concerned with the early responses to HIV/AIDS. The Revisitation includes but is not limited to the films: How to Survive a Plague, Dallas Buyers Club; the exhibitions, Art AIDS America; One Day This Kid Will Get Larger…, Tim Murphy’s novel Christodora, Alysia Abbott’s memoir Fairyland, Tiona McClodden’s artwork Af-fixing Ceremony, and the plays Thirtynothing written by Dan Fishback, and And We Should Stand Like This written by Harrison Rivers. Overall, the Revisitation has been positive, carving out space for healing, hearing, and reunion. And yet, as myself and others have noticed, there is a narrowness within the Revisitation. With a few exceptions within the Revisitation, there is an overall absence of people of color, of women, of black people, of trans people, of people in rural America, people who inject drugs, who do sex work, who live in poverty, and people who live at intersections of all of these ways of being alive. I see the work coming out of the AIDS Crisis Revisitation and I think: where are all the people? Why am I only seeing different versions of me? It is not that the story of white gay men in the face of the plague does not matter, it does. It does. It is just that it is not the only story, and in a patriarchal culture of white supremacy, it gets treated as the beginning and the end of the story.

I avoided watching the short film on the David Kirby photo. As someone working at the intersection of art, AIDS and activism, I too, as a white, gay, HIV negative middle-class, cis man, have failed to acknowledge Peta and I couldn’t bear the thought of the film doing the same. But I was provoked into watching it after attending a panel this summer about queer literature and the panelists discussed both the absence and presence of new AIDS related culture being made. I felt the need to weigh in. So, sitting one night at a writing residency, I watched the film. Early on, Peta appears through photos. I gasped. Would I hear someone other than me and the friend who jump-started my research on the photo say Peta out loud? No. Peta is never named. Referred to only as caregiver. And then, only in passing.

Black feminist ethicist Dr. Traci West tells us that our ethics form where the story begins, and our ethics are revealed in our actions. When you look at the work coming out of the AIDS Crisis Revisitation, the stories often begin—mirroring the focus of the Revisitation—with photos, like the one of David Kirby: a white gay man, to be pitied, to be feared. And so, isn’t Dr. West so painfully right? The bulk of our actions in response to HIV have been, and still are, focused on white gay men (or making a big production of it when they are not). So what would it mean if we pulled the camera back, and started the story with that which has been obscured, cut off, neglected? What would it mean if we told the story of HIV through Peta? Through people whose land has been stolen? Through people whose gender the culture refuses to see? What if we told the story of HIV through the visible hand of friendship?

HIV is first and foremost a material reality, which lives in some people’s bodies and not in others, the reasons for the disparity, intimate and systemic in scale. It is also a cultural phenomenon, shaped by us. AIDS is a rolling cultural inheritance, a spectacle that looms overhead, shaping prose, poetry and desire. As a fellow writer, I hope you accept this little bit of information I have about Peta, and transmit it to others, replicating the love without fear.