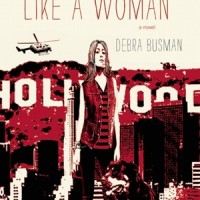

‘Like A Woman’ by Debra Busman

Author: Sarah Burghauser

March 26, 2015

Not every female character in Debra Busman’s new feminist novel Like a Woman is a hero. While unraveling the ways women move through and deal with a punishing patriarchal world in which moments of redemption are evasive and seem futile, Like a Woman manages to reveal the abuses girls and women face and who they become as a result of living in a violent, masculinist society, in a way that challenges contemporary post-feminist bunk.

The protagonist, Taylor, is from a working class family plagued by fear, assault and substance abuse. At age fourteen, when circumstances make it impossible for her to live at home any longer, Taylor doesn’t so much run away as she does move on to stomp through the wastelands of Los Angeles working her every bit of wherewithal to the teeth. No matter what travails she encounters on her journey of survival, Taylor forges ahead with morality, instinct, resolve and even swagger.

There is nothing Taylor can’t handle. An unpredictable, alcoholic mother? Taylor’s perfectly capable. A fight with her only comrade while on the street? She knows what to do. Pedophilic johns? Bring it on.

Yet, this is more than a lesson in the badassery it takes to survive in a world where everyone and everything seems to conspire against you. This story also unpacks the complexities and tensions that accompany life as a young woman on the street while delving into the specificity of this character’s experience.

The narrative switches between first, second, and third-person throughout, offering its characters’ perspectives from every angle. Diaristic interludes also act as another kind of viewpoint. At first, we’re sure these words are Taylor’s. Yet, as the story progresses, we begin to question whether they might belong to someone else, as well. This is particularly true in the hefty middle section of the book, which follows Taylor’s time with her enlightened street lover Jackson.

Jackson, the writer of the pair, in response to Taylor’s question, “Why you gotta write it like you’re way up high, looking down on everything,” explains, “It’s called perspective… The bigger picture. To write well, you’ve got to be aware of everything.” Jackson’s meta-literary observation is one of many such moments where someone tries, often in vain, to show Taylor something important about her life.

Hearing multiple voices enables readers to see that while the particulars of the protagonist are unique, Like a Woman remains about what girls go through, how girls become women, and the brutality they brave along the way no matter their class, race or sexuality. Jackson, for instance, points out that she and Taylor don’t have to know everything about their friend Jo-Jo, who met a tragic end, to be able to tell her story.

However, in a book about the fidgeting line between girlhood and womanhood, it’s the mothers’ perspectives that are curiously absent. With the glaring exception of Jackson’s sagacious mother (who is deceased notwithstanding), all mothers’ are exposed as violent and dysfunctional. In this world, mothers are alcoholics, abusers and even murderers.

Mothers, according to one interlude, exploit their children’s desire to please them: “It is the daughter’s job to keep her mother alive.” One of the most disturbing features of parenthood in this book is not that there are some bad parents, but that they’re all positively evil.

While the lived, complex interplay between race, poverty and gender is central to this book, it also takes a stab at the question, “what are women like?” The answer provided is sobering: it teaches us that women abuse just like men, as is the case with Mrs. Doyle, who beats her disabled son to death; that women are alcoholics, like Taylor’s own mother; or, conversely, that women are graceful and generous like C.N., or smart like Diane and Shantelle, or wise like Jackson, or fatally unlucky like Jo-Jo.

But more than the doomed relationships between mothers and their children, or questions about “women’s nature,” the chapter titled, “Just Another Way to Bleed” hints at the core subject of this book: the female body and all the ways it is exploited. The book finally concludes that the only universal experience of womanhood or of femaleness is that it’s hard—existentially, physically, ethically and mortally hard. Yet, we never feel bad for Taylor or for any of her comrades. Neither pity nor worry come into play. Readers are more likely to find themselves raging along with Taylor in her indefatigable stamina for encounters with the rotten.

Respite and hope come not from relationships with other human beings, but rather from the natural world. Despite her entrenchment in the urban, Taylor’s connection with the wild, particularly with undomesticated animals, proves essential. It is during these interactions that Taylor’s intuition, strength and tenderness truly emerge.

The archetype of the wild lesbian woman and her mare companion comes to new life in a most touching scene when Taylor attempts to lasso the wild filly, Fancy Dancer. Through this encounter, Taylor sees herself anew and begins to understand Jackson’s mother’s words, “…we are so much more than what was done to us.”

In prose as lucid and passionate as any manifesto, this contemporary feminist anthem offers us a hero who both charms and challenges readers by way of her acuity, grit and depth. Like a Woman is destined to be a classic.

Like A Woman

By Debra Busman

Dzanc Press

Paperback, 9780393244649, 256 pp.

April 2015