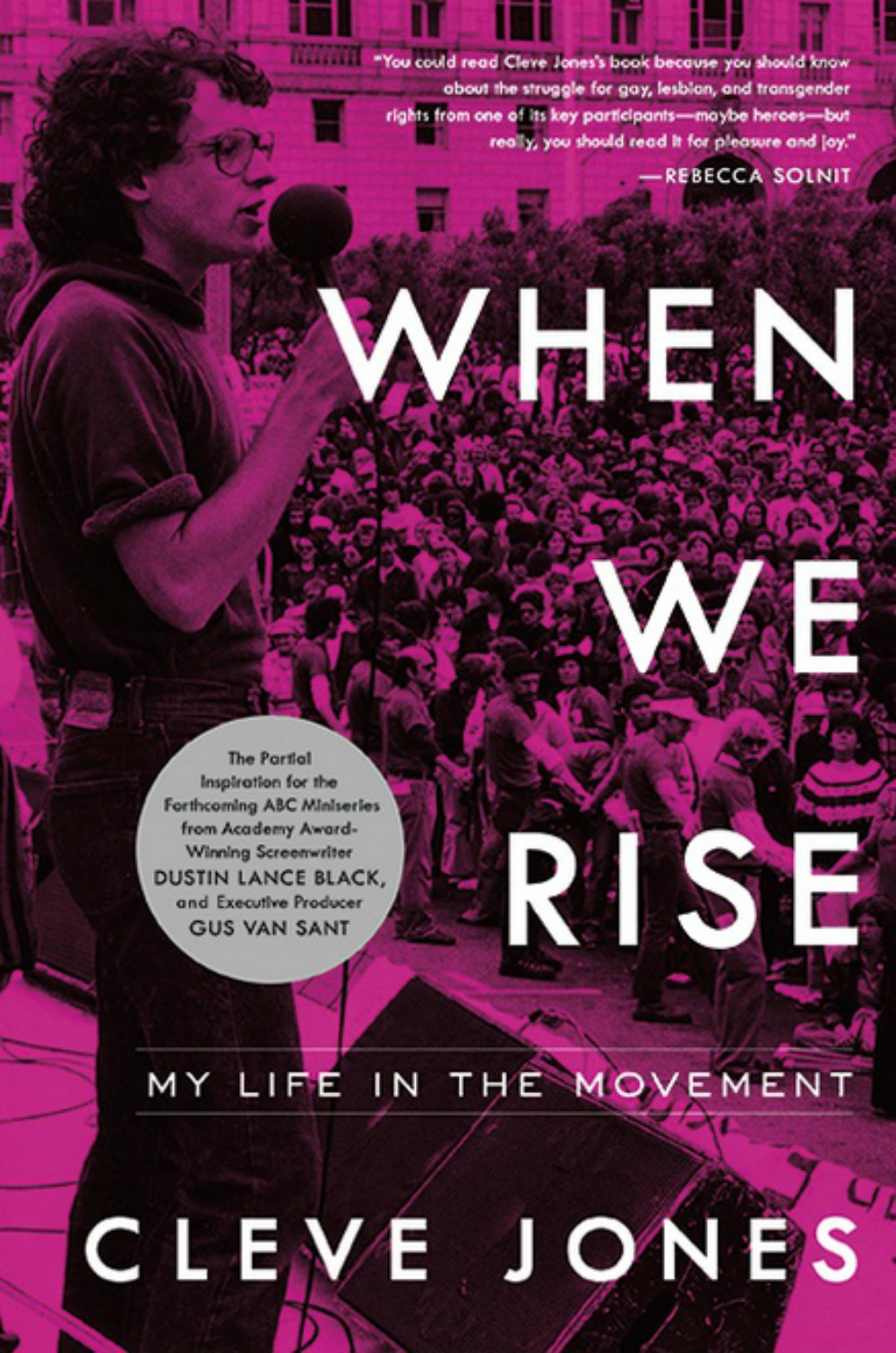

‘When We Rise: My Life in the Movement’ by Cleve Jones

Author: Walter Holland

December 13, 2016

Cleve Jones’ memoir straddles both the demands of an intimate personal portrait of a gay man at the end of the twentieth century and early twenty-first century, and an in-depth historical record of the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and trans movement in America. Interspersed in Jones’ story are also key events in American history over the decades, both political and cultural, usually handled by short summary paragraphs, which review historical events over the years, e.g. 1975: the Watergate cover-up, the Weather Underground’s activities, Bowie’s “Fame” and Earth, Wind and Fire’s “Shining Star for You to See.” These chart a timeline of sorts, milestones, which mark the author’s growth and development as well as that of the country at large.The first half of the book deals with Jones’ early life, his trials and tribulations in Arizona where he grew up, his penniless entry into San Francisco where he partakes in its sexual liberation of the 1970s and is first introduced to its burgeoning gay bohemia. Later he travels abroad and spends time in both Paris and Munich. In Paris he is told by a handsome law student: “In France, we respect individual privacy, we do not feel obliged to share the intimate details of our romantic and sexual lives with the general public,” a flat out rebuke to the American LGBT movement to come where “coming out of the closet” was imperative to building gay power.

It is perhaps in the second half of the book–when Jones’ encounters his mentor, Harvey Milk, in San Francisco and begins his true political life as an organizer and activist–that Jones writes at his very best and his most informative.

Here we get the full gay excitement of the Castro district and the growth of San Francisco as an LGBT mecca:

Every day brought more gay and lesbian immigrants, fleeing intolerance and violence for San Francisco. The platform shoes and glitter of the 70s gave way to a new look, derisively labeled “Castro clones” by Arthur Evans. The hippie look of long hair and bell-bottoms was gone. The ‘70s disco look of platform shoes and glitter was disappearing. The men of Castro Street now wore work boots, plaid flannel shirts, tight T-shirts revealing broad chests and biceps, and straight-leg Levi’s 501 button-fly jeans . . . As word of what was happening in San Francisco spread, and as the backlash from the right grew more intense across the country, more and more people arrived […]

Here Jones’ story becomes also more gripping, including the advent of Harvey Milk on the political scene, the events leading up to Milk’s murder by Dan White, the murder itself, the later advent of AIDS, the founding of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, Jones’ own AIDS illness, and his subsequent work in union politics and beyond:

I float to the door of White’s office and peer in. There is a cop there, on his knees, turning Harvey’s body over. I see his head roll. I see blood, bits of bone, brain tissue. Harvey’s face is a hideous purple. I feel all the air leave my lungs. My brain freezes. I cannot breathe or think or move. He is dead. I have never seen a dead person before.

[… ] They come from all over the Bay Area: young and old; black and brown and white; gay and straight; immigrant and native-born; men and women and children of all races and backgrounds streaming into Castro Street—Harvey’s street—faces with wet tears, hands clutching candles. Hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands fill the street and begin the long slow march down Market Street to City Hall, a river of candlelight moving in total silence through the center of the city.

There is also a fascinating chapter on the making of the film Milk in 2008, directed by gay filmmaker Gus Van Sant and written by Dustin Lance Black. Jones explores the legend of Harvey Milk versus the reality of the actual man as well as the complicated process of lifting a seminal piece of history and theatricalizing it.

As Jones alludes to in his lectures or teaching of millennials, every year much of the LGBT history he so assiduously details is being lost to ignorance and apathy. San Francisco itself has become too pricey for the very artists, activist and middle class that made it so richly creative a place. It is to this end that Jones’ book succeeds as a sort of primer to LGBT youth about the history of the movement and those key characters that figured in its advancement. He does a nice job especially of summarizing the recent advances in the past few years with the overturn of Proposition 8 as unconstitutional, the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and the famous opinion of Justice Kennedy in Obergefell vs. Hodges that essentially legalized same-sex marriage. He also is successful throughout the book with teething out the intricate political strategies, pro and con arguments and necessary alliances needed to advance the gay rights cause.

Having had a front row seat to history, Jones gives us an honest appraisal of his feelings and opinions, e.g. he admits to finding Larry Kramer’s ACT-UP organization in New York City “to be just a bit of a clique,” the membership being “overwhelmingly white and male and under 40.” He describes the opposition gay organizations gave to the American Foundation for Equal Rights when it challenged California’s Proposition 8 in federal court; the arguments to take it slow and not confront the system too aggressively.

All this makes for compelling reading. I was instantly reminded of other gay diarists and memoirists who sought to passionately chart the momentous changes and upheavals both culturally and politically that enveloped their lives. A writer such as Gad Beck during the Nazi era in Germany or more recently Randy Shilts (an acquaintance of Jones’) or David Wojnarowicz during the AIDS years in America. All in all, this is a mandatory read for future scholars of LGBT history and for queer millennials to learn about their heritage.

When We Rise: My Life in the Movement

By Cleve Jones

Hachette Books

Hardcover, 9780316359528, 304 pp.

November 2016