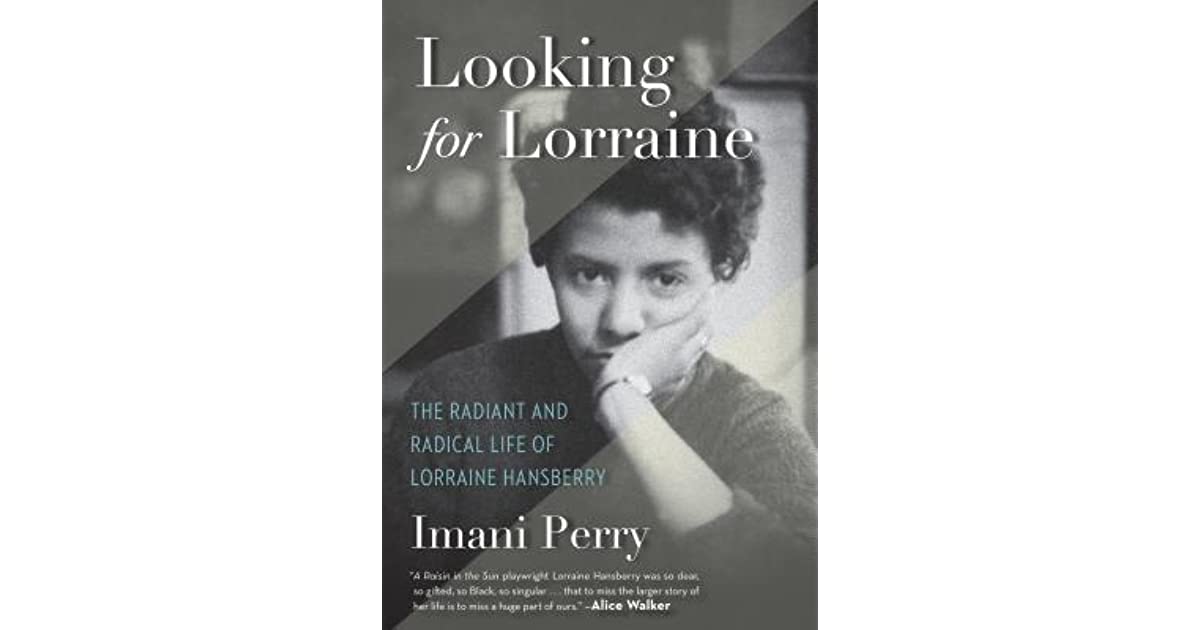

‘Looking for Lorraine: The Radical and Radiant Life of Lorraine Hansberry’ by Imani Perry

Author: Sarah Fonseca

November 6, 2018

“Unexpectedly but appropriately, in the twenty-first century, after death, Jimmy [Baldwin] and Nina [Simone] were reborn as icons on posters and pillows and in books upon books. Lorraine has yet to be,” Imani Perry writes in her new biography Looking for Lorraine: The Radical and Radiant Life of Lorraine Hansberry. Perhaps this kind of rebirth has been slow to come to Hansberry because she was so unabashedly Marxist; as the Che Guevara t-shirts have shown us, to purchase the Marxist as a commodity is to make a fool both of oneself and the cultural figure’s core beliefs. How do we pay visible homage to Hansberry, a black lesbian woman who saw herself as a mere string in the revolution’s fabric, who had a habit of quoting her mentor W.E.B. Du Bois’ collectivist words? “Somehow you have got to know more than what you experience individually.”

Yet since Perry committed this observation about Hansberry’s lack of a second coming to paper, we’ve come closer still: A revival of her second Broadway play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, was staged in late 2016 at the Goodman Theater in her native Chicago, and 2017 saw Tracy Heather Strain’s documentary Lorraine Hansberry: Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival and then run on PBS’s American Masters series. In the past month, A Raisin in the Sun—directed by Daniel Petrie from Hansberry’s meticulously annotated screenplay—was welcomed into the Criterion Collection’s fold. We find ourselves in the optimal moment to encounter Hansberry, with her likeness and words being revisited, but thankfully, not yet appearing on graphic t-shirts or cross-stitched Etsy tchotchkes.

Perry’s title Looking for Lorraine references Isaac Julien’s New Queer Cinema film Looking For Langston, and the book’s eleven chapters mimic the film in execution, in the sense that they do more than merely offer a linear grasp on the circumstances that brought Hansberry into this world, kept her furiously busy in life, and took her out. While structured around examinations of Hansberry’s journals, manuscripts, and the early radical newspapers for which she worked—and her own invaluable lit scholar soundbites on those—Perry is as committed to the unknown as she is to dutiful research, and she tastefully intertwines her own biography (one also marked by Southern upheaval, chronic illness, and interracial relationships) into the text’s prologue and epilogue.

At 200 pages, Looking for Lorraine is the lengthiest Hansberry biography available today. It does more to evoke Hansberry personally than the other scholarship on her work—and considerably more than To Be Young, Gifted, and Black, her ex-husband and literary executor Robert Nemiroff’s posthumous play comprised of her unpublished writings, cherry-picked and polished. Until now, what has been largely missing from the body of work on Hansberry is, damningly enough, Hansberry herself. Her personal papers remained under lock and key until 2000, when the Lorraine Hansberry Literary Trust—founded by Nemiroff and later run by his second wife—deposited them at New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. (Despite his sustained cultural prominence, similar archival dilemmas plague the work of Hansberry’s writing confidante and friend, James Baldwin; many of his letters acquired by the Schomburg remain under a 20-year seal.) But Perry is unwavering in her choice to convey the whole of Hansberry’s life, writing, “She drank too much, died early of cancer, loved some wonderful women, and lived with an unrelenting loneliness.”

Fourteen years after the Schomburg received Hansberry’s papers, some of those documents became widely available to the public when her anonymous letters to The Ladder, America’s first lesbian magazine, were exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum’s Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Not only was the world realizing that one of the most formidable voices in Civil Rights Era America was queer, they also saw the humor with which she approached the scarlet letter of her own lesbianism. Writing of Hansberry’s lesbian fiction published under the name Emily Jones, Perry notes:

The […] distinctive feature of the Emily Jones fiction, for me, is found in its aesthetics. Lorraine reveled in female beauty. She poked fun at Simone de Beauvoir’s hypocrisy in harshly judging women’s adornment: ‘The writer brilliantly destroys all myths of woman’s choice in becoming an ornament; and the charm of it is the photograph then on the dust jacket which presents a quite lovely brunette woman, in necklace and nail polish—Simone de Beauvoir.’ Lorraine teasingly suggested that perhaps it was pleasure and not just constraint that shaped the Parisian philosopher’s style.

Prior to the Brooklyn Museum show, outing Lorraine to readers fell to a niche alliance of older lesbians, who once found community with Hansberry in Manhattan’s mob-run dyke bars, and younger ones, like Elise Harris, who found the subject fascinating. Twenty years ago next September, Harris’ article The Double Life of Lorraine Hansberry appeared in Out Magazine, in which these older women, many of whom are now dead, grappled with the record that the archive refused to set.

It is a relief that it is Perry who is the first to access the Hansberry papers in their fullest form to date, though there are destined to be others. Perry welcomes them: “Her essays, her excerpts, her heart and mind put down on paper will be pored over,” she writes. “Her pages lie in state at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture up in Harlem, right near the Speakers’ Corner Lorraine once preached from. She is waiting for us.”

Looking for Lorraine: The Radical and Radiant Life of Lorraine Hansberry

By Imani Perry

Beacon Press

Harcover, 9780807064498, 256 pp.

September 2018