‘The Tradition’ by Jericho Brown

Author: David Eye

September 15, 2019

___[…] I keep trying to be a sound, something

You will remember

Once you’ve lived enough not to believe in heaven.“Deliverance”

___[…] Somebody ahead

Of me seeded the fruit-

Bearing forest. The night

Is my right. Shouldn’t I

Eat? Shouldn’t I repeat,

It was good, like God?“After Essex Hemphill”

If—IF—Jericho Brown’s first two books (Please and The New Testament) could be reduced to, respectively, Body and Bible, then The Tradition is the Book of Brown. Gone are the visceral, violent verses of Please (along with allusions to popular song); ex(or)cised are Christianity and the liturgical tone of much of The New Testament. Instead, The Tradition is rich with music and spirituality—of Jericho Brown’s own making. Here, in received and new forms, the language is plainspoken and concise; the voice(s) self-aware, self-reliant, seasoned. The Tradition is a lesson in the power of craft: these poems are as twisted and tightly braided as the mane of hair in “Monotheism,” where Brown just comes out and says it: “Some people need religion. Me?/I got my long black hair.”

With The Tradition, Brown stakes a claim within the canon, positioning himself alongside (and in conversation with) other eminent American poets—on his terms. He even invents a form (the “duplex”) to get at all that. The two excerpts above represent (to me) what Brown is doing in this book and whom he owes; he’s working within a tradition while forging something new.

With The Tradition, Brown stakes a claim within the canon, positioning himself alongside (and in conversation with) other eminent American poets—on his terms. He even invents a form (the “duplex”) to get at all that. The two excerpts above represent (to me) what Brown is doing in this book and whom he owes; he’s working within a tradition while forging something new.

The book is called The Tradition—singular—but there are a slew of traditions here, by turn examined, played with, or outright flouted. Brown reveals (in an interview with Bennington Review) that these include “the sonnet tradition, the tradition of racial injustice in this country, the tradition of continuing to plant gardens.” But there are more: Blackness, Black poetry, Queerness, Whiteness, Western mythology, education. Even Brown’s own tradition seems to be a subject. And if we can already say there is a Queer American poetic “tradition,” Brown, surely one of its forebears, solidifies his place with this book.

I present myself that you might

Understand how you got here

And who you owe.

____“Meditations at the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park”

Whom does Jericho Brown “owe”? In The Tradition, he is in conversation with a big family: Mari Evans, in the opening epigraph. In “Stay,” he uses a line by Gwendolyn Brooks to craft a “golden shovel,” a poetic form devised by Terrance Hayes. His poem “The Hammers” is after Marie Howe’s “What the Angels Left.” He also writes “after” James Baldwin, Essex Hemphill, and Avery R. Young, and throughout the book, there are unnamed but unmistakable nods to Margaret Atwood (see below); Lucille Clifton (in his homages to various body parts); Langston Hughes; even William Carlos Williams and old Mr. Frost: “…and I, / I am reminded of all I’ve gotten / Rid of” (“The Rabbits”).

* Please note: “in conversation with”—not “influenced by.” *

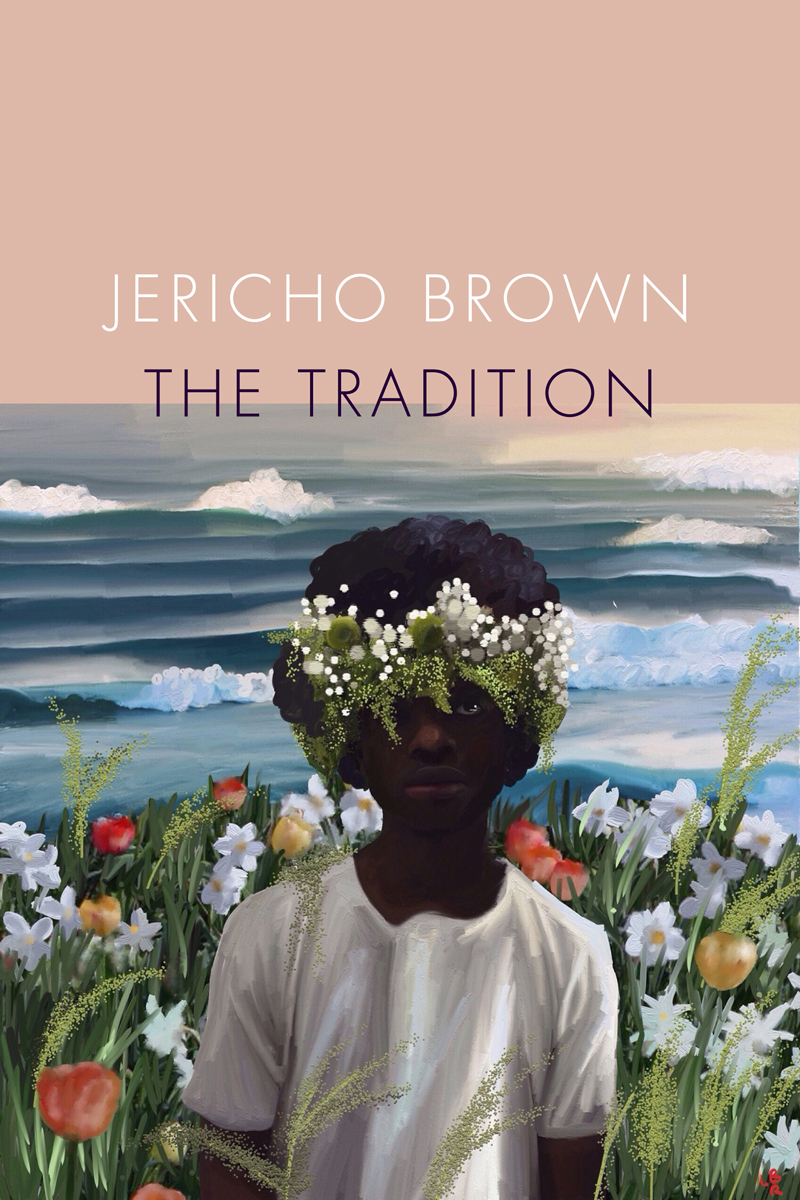

In a discussion of the arresting cover painting (Lauren Ralphi Burgess’s “You’re in the Middle of the World”) in an interview with The Rumpus, Brown observes that “Everything is muted enough so that if you have feelings about what you’re seeing, then they’re your feelings. They’re not feelings that we’re putting on you.” He’s talking about the cover, but I would argue that the poems behave similarly. The emotional content in these verses is muted, subdued. Which is not to say there’s anything tepid about the language or the book. There is a subtle urgency to these poems, heightened and intensified by the forms and other elements of craft that Brown uses (and subverts).

Themes, in addition to the above “traditions,” include sexuality, rape, complicity (everyone’s) in the face of violence and inequality. And HIV, which receives both a humorous prose poem (“Cakewalk”) and a still-threatening voice in “The Virus”:

[. . .] I want you

To heed that I’m still here

Just beneath your skin and in

Each organ

The way anger dwells in a man

Who studies the history of his nation.

Not all of the poems are straightforward. There’s an intriguing handful of mysteries near the middle of the collection, all persona poems. Who are these speakers? Captor, captive, others complicit in rape or murder. Brown, in the Rumpus interview: “I knew that there would be moments at which the reader would be questioning what was going on…. [T]he difference between the poet I am now and the poet that I was before, is that I understand the value of that.”

“I am not the man who put a bullet in its brain / But I am commissioned to dispose of the corpse. . .”

In this poem, “Shovel,” the speaker is not the perpetrator, but is complicit in violence, bringing to mind (and gut) Atwood’s chilling “Footnote to the Amnesty Report on Torture” in which the central figure “isn’t a torturer, he only / cleans the floor.”

Brown is writing in taut, compressed lines, as contrasted with the longer line and discursive language of many of his peers. These poems are above all musical, suffused with meter and rhyme, whether embedded or more obvious. Many of the poems adhere to patterns of syllable count or metric feet. In “Dark,” for instance, though it doesn’t appear as such on the page, when read aloud, these and other lines are in tetrameter (four beats or metric feet per line), further accentuating the blues from which this and other poems spring:

____________I’m sick

Of your hurting. I see that

You’re blue. You may be ugly,

But that ain’t new.

In this poem (placed near the end of the collection), Jericho Brown the person addresses (by name) “Jericho Brown” the public persona. The mask cracks and falls; the speaker shows the self. The poem is audacious. It is disarming. It is also endearing. It evidences a level of self-awareness which, coupled as it is with craft, makes for a powerful, mature, and moving moment, emblematic of the self-assuredness—and vulnerability—of this collection.

Much is likely to be written about Brown’s invented form, the duplex, a form that appears five times in the collection. Representing one of his attempts to “gut” the sonnet, the duplex contains elements of the sonnet, plus the ghazal, plus the blues. (For more, see Brown’s own blog post on “Invention”.) Subtle shifts (e.g., in person, in pronoun, in part of speech) from one repeated line to its next utterance are used to clarify, qualify or intensify, creating a slow, satisfying unfolding.

I would like to elaborate on this form, and to go on about the other tricks up Jericho Brown’s sleeve—

- the use of repeated phrases within lines, or in successive lines, for sound, for reinforcement, for the blues

- the rhymed and/or metered final couplets, which have the effect of snapping shut or lowering the curtain on (otherwise) free verse poems

- the poems’ anti-sentimentality

- the (paradoxically poetic) acknowledgement of the limitations of poetry, as in “I am tired / Of claiming beauty where / There is only truth.” (“The Rabbits”)

- et cetera

—but space doesn’t allow.

I close with the epigraph that opens The Tradition, the first stanza of Mari Evans’s “Celebration”:

I will bring you a whole person

and you will bring me a whole person

and we will have us twice as much

of love and everything.

I invite you to bring your whole person to this fine new collection. In The Tradition, Jericho Brown has brought us his.

The Tradition

By Jericho Brown

Cooper Canyon

Paperback, 9781556594861, 384 pp.

June 2019