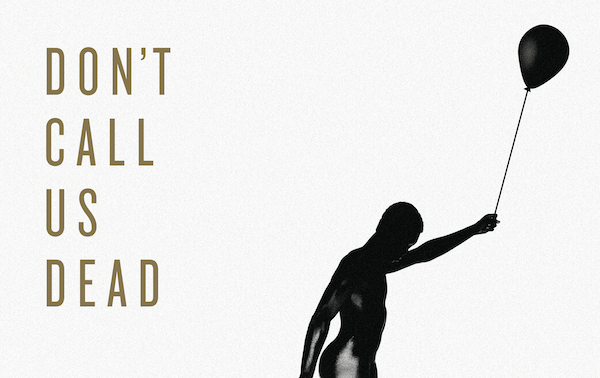

‘Don’t Call Us Dead’ by Danez Smith

Author: David Eye

January 15, 2019

America might kill me before i get the chance.

my blood is in cahoots with the law.–“every day is a funeral & a miracle”

i did not come here to sing you blues.

lately, i open my mouth& out comes marigolds, yellow plums.

i came to make the sky a garden.–“tonight, in Oakland”

This is not a traditional review. There will be no attempt at critical distance here.

This book made me slam it shut a few times to keep from weeping in restaurants. Not because the poems are sad. Or because they are joyful. But because they are both, and neither. They confront the world(s) we live in (e.g. “you’re dead, america”) and imagine others (e.g. “summer, somewhere”) in ways and in language so precise and evocative that we lament and yearn right along with these searing, soaring poems.

Danez Smith identifies as a “Black, queer, poz writer & performer from St. Paul, MN.” My first experience with them (Smith’s pronoun of choice) was at a Prince-themed poetry/dance party at First Avenue in Minneapolis, one of the locations for Purple Rain. Smith read what must be the dirtiest, funniest, and most celebratory butt-sex poem in the world. Their first book, [insert] boy (YesYes Books, 2014) won the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the Lambda Literary Award.

Don’t Call Us Dead (Graywolf Press, 2017) is Smith’s second, and it was a finalist for the National Book Award. The long-form poem “summer, somewhere” that comprises the book’s first section was awarded the inaugural T. S. Eliot Foundation and Poetry Society of America’s Four Quartets Prize this April. The award “honors a unified and complete sequence of poems” and the judges said that “From a bitter landscape, this unblinking sequence manages to wrest a celebration of black lives, fusing metaphor and emotion in a transformative whole.”

The same could be said of the whole collection. There is hope alongside despair; beginnings beside (and inside) devastation. And while many of the poems are elegiac (in that they lament the dead), they are also anti-elegy, beyond elegy. “summer, somewhere” gives us a speculative world where all the black boys we have lost (the Emmetts and Trayvons whose “white shirts / turned ruby gowns”) are reborn:

please don’t call

us dead, call us alive someplace better.

No death, only resurrection, reincarnation. Boys play and dance again, they fly. This is a paradise where

the forest is a flock of boys

who never got to grow up.

That forest is emblematic of appearances (throughout the book) of the natural world: wise and comforting poplar trees, plums and tulips, lilacs and lavender. So the poems are staking, perhaps, a rightful claim to the land, this country: “do you know what it’s like to live / on land who loves you back?” (“summer, somewhere”)

There are fables, myths, and metaphor enough to set the mind reeling, and lines so plainspoken and sharp they go straight to the gut.

my grandmother’s hallelujah is only outdone by the fear she nurses every time the blood-fat summer swallows another child who used to sing in the choir. take your God back.

–“dear white america”

the bed where it happened is where I sleep.

–“it began right here”

& no one kills the black boy. & no one kills

the black boy. & no one kills the black boy.–“dinosaurs in the hood”

There is comfort in many of the poems, and direct confrontation in a select few. From “not an elegy”: “reader, what does it / feel like to be safe? white?” “listen to my laugh // & if you pay attention / you’ll hear a wake.” “dear white america” is Smith’s widely disseminated declaration of independence. And “you’re dead, america” seems to say, with a shift of emphasis in the book’s title, “don’t call US dead”:

i fed your body to the fish

traded it at lunch for milki know where they buried you

‘cause it’s my mouth

In Don’t Call Us Dead, Smith’s attention moves from the violence perpetrated on black boys to queerness and HIV and back to race, using startling forms and imaginative leaps. In “seroconversion,” HIV is too weird and cataclysmic to write plainly, so it gets a cycle of five fables, populated with fantastical characters: a pig boy, the gods of shovels and soil, a boy made of stale bread. The virus appears as “little ruby tongues sprouting” or soldiers “turning everything to fire.”

In other poems, Smith treats HIV more personally, for instance in “strange dowry,” where

we let the night blur into cum wonder & blood hallelujah

and the memorable and moving “crown,” a crown of sonnets that sounds a requiem for the speaker’s unborn babies. One of the most poignant moments in the collection comes in “every day is a funeral & a miracle.” Here, to reveal the speaker’s entrapment between the enemy within and the enemy without, Smith juxtaposes HIV and the police, then commingles them:

hallelujah! today I rode

past five police cars

& i can tell you about it

. . .

will i survive the little

cops running inside

. . .

i survived yesterday, spent it

ducking bullets, some

flying toward me & some

trying to rip their way out.

In “litany with blood all over,” neither the form nor the page margins can contain the stream of grief—“rivers of my drowned children”—as the words “my blood” and “his blood” cascade down the page, overlapping, overflowing, filling the next with words that are no longer words, the two bloods no longer distinguishable.

And, despite everything, there is a stream of love, tenderness, and nurturing running through this collection. Those boys in “summer, somewhere” are mothered/fathered/midwifed by the speaker. In “at the down-low house party,” the lines are taut with lust and posturing, and then the last line, with its yearning and hope (which I won’t spoil here), made tears spring to my eyes.

Tempting as it is to include the poem that closes the collection, it must likewise be discovered and relished in situ. Here, then, is the penultimate “little prayer,” in its entirety:

let ruin end here

let him find honey

where there was once a slaughterlet him enter the lion’s cage

& find a field of lilacslet this be the healing

& if not let it be

Dear a/America: Pay attention to Danez Smith. Read this book. But maybe not in restaurants.

Don’t Call Us Dead

By Danez Smith

Graywolf Press

Paperback, 9781555977856, 104 pp.

September 2017