Tommaso Speretta on His New Book ‘REBELS REBEL: AIDS, Art, and Activism in New York 1979-1989’

Author: Theodore Kerr

November 25, 2014

There is a way in which early responses to HIV/AIDS through activism and art are more intelligible now than they were even a few years ago. In part, this is due to the recent surge in cultural productions about the early days of the AIDS crisis in the U.S. and the bravery and generosity of those who were there telling their stories. Movies like United in Anger (dir. Jim Hubbard, 2012) and How to Survive a Plague (dir. David France, 2012), exhibitions like ACT UP NEW YORK: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987—1993 (cur. Helen Molesworth and Claire Frace, 2009); and the ongoing work of organizations like Visual AIDS mean that history is still being made, as well as curated, interpreted, understood and shaped.

The power of much of what may be called the AIDS crisis revisitation in culture comes from the urgency that those involved show in ensuring that this history is told in spite of the silence around AIDS in schools, in the media and from the government, as well as after a period of long silence about AIDS. The projects make use of and draw attention to available resources such as the ACT UP Oral History Project and the Downtown Collection at the Fales Library at NYU.

With all of this in mind, we can understand that cultural production that comes out about the early response to AIDS bears the burden of being interesting to younger generations and those who were not there, and also to get the history as complete and accurate as possible. There are real consequences when cultural production about social movements is wrong, skewed, too biased, etc. Hugh Ryan wrote about this in his op-ed for the New York Times, “How To Whitewash a Plague,” about the New York Historical Society’s 2013 exhibition AIDS in New York: The First Five Years, which largely left out the activist response to HIV. Cultural production around the history of HIV/AIDS matters as the crisis continues. As we consume the past, we need to be conscious of what we are taking in. In the case that the history is inaccurate or contestable, what do we do?

Joining this ever growing complex trans-discipline dissemination of memories and material is the book REBELS REBEL: AIDS, Art, and Activism in New York 1979-1989 by Tommaso Speretta (mer. Paper Kunsthalle, 2014). Designed by the well-regarded Venice-based graphic design duo Tankboys and edited by Rujana Rebernjak and Jonah Goodman, the book is a handsome short read that looks at the work of artist collectives Group Material and Gran Fury, and the activist group ACT UP in the context of public art, AIDS and social change.

In this interview, Theodore Kerr and Speretta discuss the power of art and activism, representations in regards to HIV/AIDS, Kerr’s frustrations with the book, and Speretta’s belief in the power of activist artists.

What drew you to write REBELS REBEL?

It’s a project I’ve had in mind since college. It was a period when the concept of public art was on everyone’s mind, as it was a debated topic among art critics and researchers, in general. I was on one hand fascinated by the idea of art happening in public, but on the other hand skeptical that this kind of art was considered public because of physical location. I asked myself, “Is installing a sculpture in a public space sufficient enough to be defined as public?” I was looking for a different kind of public art–one that could provoke some form of engagement with citizens and individuals outside the usual art circles, and that really addressed the need for involving a wider audience. I wanted to demonstrate that art could be socially relevant. I found that in the anti-AIDS art activism of the 1980s in New York. It was the perfect example of what I was looking for.

Who did you write it for? Who do you see as the audience?

The history of the anti-AIDS activist movements in 1980s America is still largely unknown, especially to the European audience. Later, I realized that the work I was doing was relevant for the American audience, too. I had been wrong in my conviction that AIDS activism history was part of the common knowledge in the U.S. The younger generations still do not know the stories I am talking about in my book. I would say that it’s for them—for the people of my generation—that I wrote REBELS REBEL.

This said, my aim was not to give definitive answers to how art as activism should be conceived today, or to which directions it should take in the future, or to criticize the logic of the contemporary art world and market. Rather, it was to open up critical reflections on the role that artists and the art world system have had in the past during periods of political and cultural instability and to investigate their historical echoes and cultural legacy. I use the experiences of ACT UP, Gran Fury and Group Material not to trace a comprehensive history of activist art, but rather as examples that might help us to identify, examine and reappraise the artistic inventions and interventions of activist art collectives that helped reformulate society’s priorities and demands.

How did you decided to focus primarily on Group Material, Gran Fury and ACT UP?

REBELS REBEL is a chronological survey of activist art in New York from 1979 to 1989 that reviews the radical responses that artists gave to social problems, especially the AIDS crisis, in the conservative political climate of their day. My research aimed to investigate the political dimensions of art practice through a comparative analysis of different cultural models, including the roles artists, art institutions, curators and society in general play in the creation of examples of activist art.

I wanted to focus on activist art as a potent manifestation of public art, through which artists and art practice can shape and change society. Group Material and Gran Fury’s struggle was the same—namely, to question art’s capacity for rebellion, subversion and social dynamism, and to reach out to a wider audience that exists beyond the circles of art connoisseurs.

Why was it important to start in 1979?

REBELS REBEL is organized following a chronological principle, so I had to start from one point. 1979 was an important date; between the late ’70s and early ’80s, many artists, artists’ organizations and groups started to question the art establishment and to address their practice toward social and political problems. Group Material was born in 79. In December of that year, COLAB occupied an abandoned space in the Lower East Side to organize “The Real Estate Show.” That’s where the book starts. The need to create an alternative political and cultural arena within which the responsibilities of the arts towards society could be discussed in public was at that time widely shared among an entire community of artists, who came together with the deeply held conviction that art mattered and that a cultural war in which artistic production could be seen as a useful platform for political change was effectively possible.

Julie Ault once said that at that time, the boundary between art and politics was clearly delimited. This boundary was largely shared, often with the intention of halting the contamination of art and politics. Between the late 1970s and early 1980s, the working context for an artist in New York was polarized. On the one hand, there was the resurgence of neo-expressionism in painting, helping to instigate the concept of the artist genius. On the other, there were feminist movements, anti-colonialist critiques, the fight for civil rights, punk and do-it-yourself music. A strong feeling of the necessity to claim individual rights, question authority and assume personal responsibility for having a say in society arose among cultural workers and artists.

Early in your book, you put forward the suggestion that it is inadequate to talk about public space; rather, it is better to discuss the public condition. In writing the book, I wonder how you see this relating to art and access to health care and information; to who gets to make activist art; and to who gets to express themselves in public.

I think that we should all express ourselves in public when we feel it’s necessary to make our voice heard. This is what is happening right now in Hong Kong, for instance. But this doesn’t mean that we necessarily have to use art or visual communication to achieve our goals and demands. What I did with my book is to demonstrate that there was a period when art turned out to be a successful means for social change. Art, of course, didn’t act alone. Both Gran Fury and Group Material’s main aims were to use art to engage the largest audience possible into cultural activism and to interfere with public space and opinion. This might still be a valid strategy today.

I think that it is important to ask who gets to express themselves in public, and who gets to have their activist art seen, reviewed and curated. In writing your book, how did you reconcile the fact that the majority of the artists making the powerful activist art about AIDS that were documented and reviewed were white, while those dying of and living with HIV/AIDS were—and are—not primarily white?

Yes, those dying of HIV/AIDS were not only white, they were not only men, they were not only homosexuals, and they were not only adults, too. I quote Gran Fury again: “White heterosexual men can’t get AIDS…don’t bank on it. …AIDS Kills Women. …AIDS: 1 in 61.” Even though those doing the powerful activist art I am talking about were in fact primarily white homosexual men, what I think is important is that they were not fighting exclusively for themselves but rather fighting on behalf of the collective. It turned out that they have been able to be more “powerful” than others, and they used their power to face a state of general crisis.

What do you hope activists and artists coming of age today and in the future take away from your book?

What I wanted to do with my book was to offer examples of how artists and the art world faced a period of political crisis in the past. Activism mainly means to organize a community, and this community organizing can come from the art world. I think we can learn a lot from history. My interest in 1970s and 1980s art activism in America rested not simply in retelling stories of the struggle with the establishment and the political status quo, but also in presenting those stories as examples to determine if and how art can still be an effective means for social change. We now need to understand how to translate this past into a future.

Art historian, writer and curator Johanna Burton has made the case that even Keith Haring, a well-known artist, “is not securely accounted for in the art historical canon.” How do you see activist art, art and artists associated with AIDS relating to the cannon of art history?

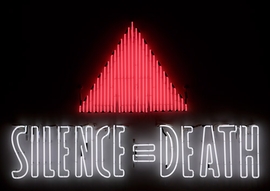

I think that we’re currently witnessing a reborn interest in the work done by activist artists and artists in protest, especially in relation to AIDS—a topic that cinema, for instance, is quite largely rediscovering—or, for example, a small but very well curated exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London entitled “Disobedient Objects,” which includes the widely lauded “Silence = Death” image, or the exhibition PERFECT LOVERS: Art in the Time of AIDS, which is currently on view at the Fundació Suñol in Barcelona, Spain. But yes, I would definitely not say that “art associated with AIDS” is accounted for in the art historical canon, but we are on the right track.

There are a few statements about ACT UP that early members disagree with, such as the idea that ACT UP felt it “crucial” to build relationships with “professionals and intellectuals in New York’s middle and upper classes;” and that art collectives such as a Gang, Little Elvis, DIVA TV, Gran Fury, Art Positive and the Silence = Death Project “condensed” their work through ACT UP. Are these statements your opinions, or are they ideas that you heard from other members of ACT UP?

I think that this is a shared opinion. These “professionals and intellectuals” didn’t act alone, of course; it was evident to activist artists that change couldn’t be brought about by individuals acting alone. They all knew that a community needed to be built; a collective consciousness had to form. This said, REBELS REBEL is not a book about the history of ACT UP but about how the engagement of the art community contributed in making ACT UP among one of the most successful protest organizations in America. What would my reaction be to people who may disagree with my book? It would be helpful to shed some more light on this matter.

Of the success of the New York Stock Exchange action that resulted in drug prices be reduced, you write, “Four days later. Burroughs Welcome announced that they would cut the price of AZT by 20%. However, the cure remained too expensive for most, costing a single patient roughly $6,000 a year.” What do you mean by cure?

I meant treatment.

I guess for me, as someone very invested in the current AIDS activist movements and the many histories that brought us to this moment, I am appreciative of your book and the work it took to make it. Yet, I am also frustrated by how that the book neglects to make clear that there are differences of opinions when it comes to what you write as history, and that the book contains errors. A cure and a treatment are two very different things. Do these issues bother you? Do you wish the publisher and/or editor went through the book one more time?

The book may contain errors, and I was sadly forced not to include many art experiences I would have loved to examine in depth. For instance, there’s a long history of how artists, and not only artists, also used video and TV to educate people about AIDS and AIDS-related issues.

We went through the book many times—maybe too many—and we changed and retouched it all constantly. I wanted to talk to the largest audience possible. I did not want to be academic at all, nor did I want to give any definitive answers. I simply wanted to tell a story and examine it thought the lens of the art history. I did not want to be pretentious or “arrogant,” and I think that this is quite clear when you read the book. I didn’t want the book to be on the universities’ desks but rather on common people kitchens’ tables.

In addition, during my research, I myself found out that people had different opinions about how and when things happened. In the end, I had to make a decision between them.

One last and very important thing must be taken into consideration: the budget for making this book was nothing if compared to any other similar book, and I am still surprised that we’ve finally been able to make it happen. I won’t see any money from the selling of the book, and I was not paid for my research and writing. It is the result of a collective effort, and I am extremely grateful to all those people who generously helped me.

Essex Hemphill’s famous poem dedicated to Joseph Beam about AIDS activism goes: “When my brother fell/I picked up his weapons./I didn’t question/whether I could aim/or be as precise as he./A needle and thread/were not among/his things/I found.” What do you see as the limits of activist art?

That poem refers to the AIDS Memorial Quilt project, about which I do not really talk in my book. In it, Hemphill criticizes the fact that the Quilt is a form of memorialization—a gesture that was not among his friend’s things. It’s a public mourning ritual, which may of course have its own political force, but yes, from an activist perspective, it might look too weak.

I think that although we are all free to decide what is activist art and what is not, the important thing to me is whether it serves its purpose or not. Gran Fury once said, “What counts in activist art is its propaganda effect; stealing the procedures of other artists is part of the plan. If it works, we use it.”

I think we can also see it as being about the limits of activist art, including the red ribbon. This is something that, as you know, Gran Fury themselves asserted with their poster ART IS NOT ENOUGH. As we enter this phase that you mentioned earlier in which there is a look back at the cultural responses to early AIDS activism, or what I call the AIDS crisis revisitation, do you think we need to also be looking at what the response through culture was not able to achieve?

Yes, of course we have to look at what was not achieved and the reasons behind it. This is also the reason why at the end of the book I wanted to include Gran Fury’s dismissal manifesto from the mid-90s. In it, among many other things, they remarked on the necessity of efficient prevention campaigns, for instance. One of the manifesto’s chapters is titled “Future Sex Acts,” and in it, members of the collective state that AIDS prevention organizations need to understand each area’s specific “community norms” in order to convey the most efficient prevention message for the future. This also amounts to identifying the lapses that need to be changed. I think that this is till true today.

Again, we should still look at what activists did in the 1980s in order to foresee what should be done today. Looking at the history is helpful to see what strategies and actions could be adapted in ways that hold significant potential for our own contexts.