Deafen the Satellites: David Wojnarowicz at the Whitney

Author: Joshua Sanchez

August 28, 2018

In 2014, I began working on a screenplay for a film based on Cynthia Carr’s biography Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz. In the four years that I’ve spent researching the life of David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992) for this project, I could not have predicted how much America would drastically revert back to the culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s, during which right-wing politicians and religious leaders often targeted and reviled Wojnarowicz’s work.

Seeing much of Wojnarowicz’s best-known photographs, paintings, films, audio recordings and writings at David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night at the Whitney Museum of American Art feels like a punch in the gut in today’s political climate. It’s both a reckoning with what he called America’s ‘ONE-TRIBE NATION’, and a call to arms for society’s many wounded minority communities.

*

The government has the job of maintaining the day-to-day illusion of the ONE-TRIBE NATION. Each public disclosure of a private reality becomes something of a magnet that can attract others with a similar frame of reference; thus each public disclosure of a fragment of private reality serves as a dismantling tool against the illusion of a ONE-TRIBE NATION; it lifts the curtains for a brief peek and reveals the probable existence of literally millions of tribes.

— David Wojnarowicz, Postcards from America: X-Rays From Hell

*

I first became aware of David Wojnarowicz in 1991 at age 15, several months before he died of AIDS. I would often spend long hours walking aimlessly and usually penniless through the corridors of La Plaza Mall, then the one and only shopping mall in McAllen, Texas. I mostly gravitated toward Waldenbooks or Sam Goody Records, reading and listening to music that I could not afford to buy. One day while browsing records, I became hypnotized by the cover of the single for U2’s ‘One’ featuring Untitled (Buffaloes) a stark photograph by Wojnarowicz depicting a herd of American bison falling off a rocky cliff, presumably to their deaths. The photo is a detail shot from an Old West diorama that Wojnarowicz found at the Museum of National History in 1989. I was haunted by this image in a way that I could not explain. I imagined the dark force driving these mighty animals to annihilate themselves instead of standing their ground. This force we do not see; it’s out of the frame. We only know something is driving them to take their own lives.

My first boyfriend, Allen Frame, was my official introduction to the work of Wojnarowicz ten years later in 2002. Frame had been living and working as a visual artist in New York since 1977 and had co-directed and adapted Sounds in the Distance with Kirsten Bates, a series of monologues written by Wojnarowicz from his days hitchhiking and hopping trains in the 1970’s. The play featured, along with Frame, Bates and several others, artist Nan Goldin and actor and artist Bill Rice, who introduced Frame and Bates to Wojnarowicz.

While Allen and I were together I received a master class in New York City’s art and theater scene. Listening to his stories from the 80s and early 90s and his experience as an activist in Visual AIDS, I learned quickly that most of the artists who survived this period had experienced the time as a black hole, a tragic decimation that was difficult for me to fully grasp until much later.

Frame participated in the Artists Space exhibition, Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, curated by Goldin, for which Wojnarowicz provided the catalog essay Postcards From America: X-Rays From Hell. In the essay, he imagines the gruesome deaths of right-wing demagogues Senator Jesse Helms and Cardinal John O’Connor. This essay caused the National Endowment for the Arts to rescind their funding the show and the catalog. After much protest and media attention, the NEA returned their funding for the exhibition but refused to fund the catalog, partially because of Wojnarowicz’s essay.

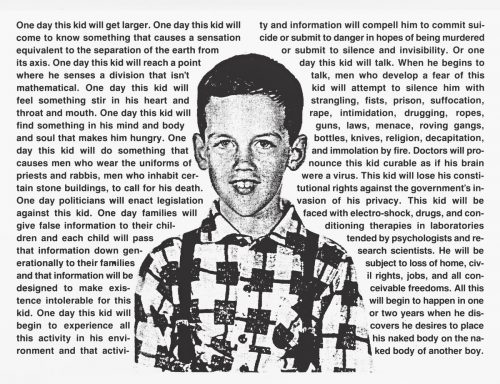

The second image I remember seeing of Wojnarowicz’s work was ‘Untitled (one day this kid…)’ a letterpress print featuring a childhood photo of Wojnarowicz surrounded by text describing the tragic fate awaiting this kid if he attempts to be honest about his sexuality.

*

One day this kid will find something in his mind and body and soul that makes him hungry. One day this kid will do something that causes men who wear the uniforms of priests and rabbis, men who inhabit certain stone buildings, to call for his death… All this will begin to happen in one or two years when he discovers he desires to place his naked body on the naked body of another boy.

— David Wojnarowicz, from Untitled (One day this kid…)

*

I had never seen a piece of art that spoke to me as directly as this piece did. As I learned more about Wojnarowicz’s work and life, I realized that we had a least one thing in common. We were both the children of abusive alcoholic fathers. David’s father hanged himself in 1976, the year I was born. My father made an ill-fated left turn in front of an 18-wheeler and died in 2005.

Wojnarowicz was by all accounts a horribly abused child. He became a teenage Times Square prostitute and then a poet who wandered across America, hitchhiking and riding freight trains. He became a visual artist in the 1980s as part of New York’s East Village art scene. Diagnosed with HIV in 1988, Wojnarowicz is best known for his work in response to the AIDS crisis, but more broadly, Wojnarowicz’s art also explores what it means to be an outsider in America.

My sisters and I were raised in the Southern Baptist church, which during my childhood in the 1980s characterized AIDS as a long overdue punishment for gays who had lived hedonistic lives of sexual abandon, practicing sodomy and pedophilia. I knew I was gay. I would sit in church and internally flog myself for having impure homosexual thoughts. I knew the world would come down on me if I dared express my desire for any kind of intimate relationship with another boy. So I withdrew. I practiced an internal discipline to please my parents, to please our god, but it was never enough to placate either.

As a teenager, I became a person that didn’t speak unless spoken to, and I lived to please other people. I was in a sense both the child Wojnarowicz in Untitled (One day this kid…) and the buffaloes in Untitled (Buffaloes) being led off the cliff by that unspeakable force. An outsider who got the message that the world would be better off, or even benefit from his not being in it.

*

When I put my hands on your body, on your flesh, I feel the history of that body. Not just the beginning of its forming in a distant lake, but all the way beyond its ending. I feel the warmth and texture, and simultaneously I see the flesh unwrap from the layers of fat and disappear. I see the fat disappear from the muscle. I see the muscle disappearing from around the organs and detaching itself from the bones. I see the organs gradually fade into transparency, leaving a gleaming skeleton, gleaming like ivory that slowly resolves until it becomes dust.

— David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (When I put my hands on your body)

*

The directness and simplicity of Wojnarowicz’s writing and his symbolic, collage style of painting and photography have the ability to transfix queer audiences and enrage right-wingers—something I’ve borne witness to many times during my research of his life. During a recent trip to the Whitney’s History… exhibition, in the audio gallery portion, I witnessed several visitors weep and commune with their partners as they gazed out the window overlooking the Hudson River, the very place where Wojnarowicz himself once cruised and graffitied the long-since demolished piers, as they listened to Wojnarowicz read selections from Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (1991) and Memories That Smell Like Gasoline (1992). Even amongst those who admire his work, Wojnarowicz’s art continues to provoke intense reactions and fierce ownership. Recently, ACT UP staged an action at the History… exhibition to protest the lack of “explicit connections to the present AIDS crisis within the exhibition.”

Wojnarowicz’s work disgusts, confuses, and inspires, often within the same piece. His work often evokes symbols of a natural world literally at odds with the mechanics of man-made objects, as perfectly illustrated in his Fire in My Belly, an unfinished Super-8mm film that got him censored from the Smithsonian’s Hide/Seek exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in 2010 because the film features a shot of a crucifix in the dirt with ants crawling on it. In the introduction to Fire in the Belly, Cynthia Carr writes that often religious symbols were not literal symbols of religion for Wojnarowicz. What the ants meant to Wojnarowicz was “humanity rushing along heedless of what lies under its tiny feet, indifferent to the structures that surround it.” He filmed ants crawling on coins, on watches, and on toys to get the same effect, but the same religious right-wingers that targeted him in the 1980s and 90s during the Culture Wars saw an easy target. Take a symbol like Jesus or the cross out of context, and suddenly Wojnarowicz is a religious bigot.

The main episode in my screenplay for Fire in the Belly concerns the battle that Wojnarowicz fought against Reverend Donald Wildmon and the American Family Association in 1990. After viewing Tongues of Flame, the catalog for the Wojnarowicz retrospective at Illinois State University in 1990, Wildmon cut out sexually explicit excerpts from Wojnarowicz’s Sex Series—which contained many other non-sexual images in collage form—and pasted these cut outs into a flyer with the title ‘Your Tax Dollars Helped Pay For These “Works of Art”’, and sent the flyer to conservative politicians and church officials all over the United States.

Wojnarowicz sued Wildmon for violation of copyright. He won exactly $1 from the lawsuit, which he considered to be a victory. You can see the actual $1 check in the History… exhibition.

*

IF I DIE OF AIDS – FORGET BURIAL – JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A. — David Wojnarowicz, October 11, 1988, ACT UP F.D.A. Protest

*

On March 13, 2018, a mass student walkout was staged across the United States demanding stricter gun control laws. A month earlier, an armed former student of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida killed 17 people with an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle. It was the 17th mass shooting in the United States this year. There have been 213 so far this year and 219 people have died.

I happened to see a photo of the walkouts online. One of the young protesters held up a sign reading ‘IF I DIE IN A SCHOOL SHOOTING DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE CDC’. The sign called attention to the lack of any Centers for Disease Control and Prevention research on gun violence, which could address the public health risks of guns on American society. While the issue had changed, the message stayed the same as when Wojnarowicz had worn the statement on the back of his denim jacket at ACT UP’s FDA Action protest on October, 11, 1988, nearly 30 years earlier. I was excited to know that people who were never alive during Wojnarowicz’s lifetime were finding out about his work and picking up the legacy of his activism. Still, I am troubled that the myth of the ONE-TRIBE NATION—the illusion that the people with all the wealth and power hold the keys to our mere existence—persists, as strongly as ever, necessitating the need for these signs.

If the 2016 election proved anything, it’s that we are as divided as we ever were. Even Obama could not erase the deep-seated ideological cracks that America was founded on. The History…exhibition shows, with dignity, power and beauty, just how intensely David Wojnarowicz wanted to lift the veil of this American myth, or the “pre-invented world” as he called it. He wanted us to see beneath the American dream—all of the grotesque hypocrisy and all of the promise—and begin to rebuild something better.

In 2018, we are far from this reveal. But as long as David Wojnarowicz’s work exists in this world, more and more people will find it and begin to peek behind the curtain. And this is where change can occur.

*

“With enough gestures we can deafen the satellites and lift the curtains surrounding the control room.” — David Wojnarowicz, Postcards From America: X-Rays From Hell