Danez Smith: On His New Poetry Collection, Writing About Gay Sex, and the Power of Blackness

Author: Candice Iloh

January 26, 2015

“Today, being black and gay is an armor, a gospel I love dearly. I love black queers. I love who and how we are. It’s taught me a lot of love; how it can surprise you with its leaps and failures.”

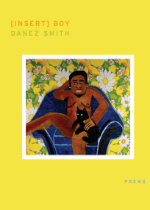

Danez Smith is a nomadic 25 year old poet and author from Minnesota. And, as he says it, black as hell. Already his work has glossed the pages of several major publications and earned him prestigious poetry awards, including the recent 2014 Button Poetry Best Chapbook Award for Black Movie. Now in comes [insert] Boy (YesYes’s Books, 2014), his debut full-length collection slick with hard learned lessons and escapades that will make you question how full of a life you’ve really lived. Here, we get a deeper peek into how this brilliantly uncensored poet wrote himself into the bigger picture.

What was it like releasing such an autobiographical debut at this point in your life?

It’s a rare blessing to hold something you’ve dreamed about so long in your hands, see it in the hands of loved ones and strangers alike. Publishing these poems in journals has been like ripping pages out of my diary and posting them on everyone’s locker. So I feel like a have practice in being comfortable [with the fact that] people will read and judge my work and, by extension, my life. I had to get rid of a lot of shame before I could become truly comfortable writing such confessional work and that’s a continual process But I’ll at least feign being fearless for now. But who knows, maybe this will be the life’s work or maybe at some point I’ll be less comfortable putting my business in the streets.

Immediately opening up your book you begin with a quote by James Baldwin on being poor, black, and gay and one of your poems is “Faggot or Where the Front Goes Up” where you share some painful realizations on growing up black and gay. What did it mean for you to be black and gay growing up?

Personally, being black and gay used to mean a lot of careful code switching, hiding, social navigating, not being too afraid to throw a fist, being really funny, and maintaining an image that rendered me more silly and less sweet. I was popular at school and a loved son in a very southern Baptist family. I learned early that to maintain that I had to shy away from whatever made my grandfather’s mouth turn sour or what might muster up a “faggot” from someone’s mouth. But what happened to faggots, I was only able to sympathize in private for my own sake. Being black was enough, I didn’t need to be anything but that.

Today, being black and gay is an armor, a gospel I love dearly. I love black queers. I love who and how we are. It’s taught me a lot of love; how it can surprise you with its leaps and failures. It’s taught me a lot about masks; where they reign and where they crumble. It feels so good to finally be me, after so many years of denying that, trying to pray what was god given away.

But immediately following, you offer us “Genesissy,” prose laced in attitude and sass that reads in an almost scriptural language with “God said bitch,werk and Adam learned to duck walk, dip, pose, death drop.” What brought on this bold blending of familiar gay colloquialism and biblical vernacular that comes up often throughout your work?

Chris Walker, Professor of Dance at the UW-Madison, is one of my biggest teachers when it comes to art making. He once said to us in workshop that we should bring our whole selves to a piece we are creating, to not attempt to segregate any part of our being from another. That. Changed. My. Whole. Shit. When I’m creating, there is no difference between what is spiritual, religious, the sexual, racial, real, fantasy, joyous or tragic.

After reading your poem “Raw” some might wince and think their blind beliefs about gay sex have been confirmed, even without having experienced it. But really, it appears to be more of a truth telling about what happens in the general sex of lives of adults. Can you say more?

Don’t we all have fears when it comes to sex? I imagine you can’t be fearless forever when you are playing around with rapture. I don’t know anyone who has sex who also has had a perfect sexual history. When two or more people engage that closely, whether or not love is also in the room, there is something there that might distract us from sense. Also, if anyone is reading this book and thinking I’m speaking for anyone but me, I got news for you, bruh.

You push the envelope a bit further with “Obey” and “10 Rentboy Commandments or Then the White Guy Calls You a Nigger.” What is most important to you about sharing personal experiences such as these?Who can write poems about me but me? These poems are poems I needed to read, and I hope those who need to see these poems get to encounter them. I’m not shy, so it doesn’t occur to me often what I should and shouldn’t share–especially in poetry, the freest place I know. I think there is a conversation to be had about censorship or what we deem sharable. But I rather talk about pushing the limits of how we write our shared and unique human experiences.

You dedicated a majority of this collection to crafting jarring lived experiences as a black man who knows violence and the constant challenging of manhood as the default. In your series “Poems in Which One Black Man Holds Another” you write, “I am learning to touch a man’s back/& not think saddle or conquer or burn” and later mention a found joy. Where is this joy birthed from through and amidst all of this?

I’m afraid I may have written about blackness too sadly. Underneath the poems, there is an undercurrent of joy that I hope pops up when it can. The mood of the poems is a response to a testing/invalidating/robbing of that joy. But being black is the greatest thing I know. I hope I didn’t mourn too much something that lives so vibrantly. I am anti-anything that’s anti-that kind of joy.

Speaking of joy, another jolting theme of [insert] Boy is this sort of family excavation. Your poem “To My Grandfather’s Prostate Cancer” isn’t what it seems. What has helped you see personal and family tragedy from such a nuanced perspective?

Reading “Life on Mars” and “The Body’s Question” by Tracy K. Smith really transformed my perceptions of grief. While there is space for loss, there is also room for celebration, spirit and a wholeness to the dead when she writes of her parents. I wanted to give my grandfather, a complicated yet loved man, an honest, proper elegy with the poems included in the collection. That attempt wouldn’t be possible without Smith’s poems and also the work of Toi Derricote, Patricia Smith, and Ross Gay.

What was it like plotting and pulling together all of the poems in [insert] Boy as a full collection?

It really was me standing over all of my poems spread across the floor or taped to the wall, often with whiskey, sometimes with a friend, and trying to make the most sense possible out of chaos. There were also a lot of hard internal conversations about whether a poem was important to me or important to the book. It would have been a shit show of a collection without the eyes of KMA Sullivan and Phillip Williams at YesYes’s Books. Writing the poems was the hard part. Putting them together was playtime.

“Song of the Wreckage” feels like the poem of all poems citing so much of yourself, your view of history, of racism, of the world where you seem to leave it all on the stage. How are you moving forward after completing such an intense project?

“Song of the Wreckage” is a really nice failure in my eye. So I scrapped what I didn’t need and took what now exists in the book forward. I think writing it did, however, lay a seed for the two manuscripts I’m currently working on. It’s a long poem called “summer, somewhere” which plays with magic and science fiction to build a paradise for murdered black boys in verse. “Song of the Wreckage” was me attempting what I feel like I can more accurately do in this new project.

What is it that you hope to accomplish with your poems? What is all of this work for?

I just want to be useful. I can only write about what I know how to write about. The things that feel important and urgent to me. But if I think about purpose too much before the process I will never be able to write those poems. I just want to be useful enough to help something grow.