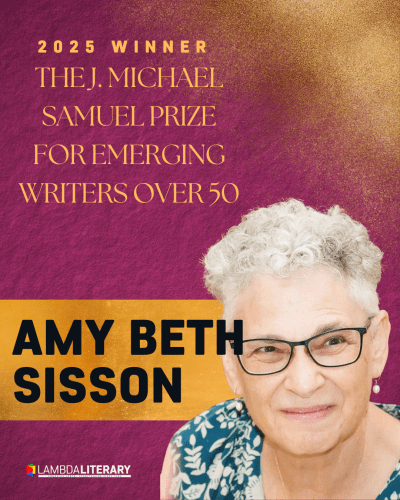

We sit down with 2025 Samuel Prize winner Amy Beth Sisson. Amy Beth (any pronouns) lives near the skunk cabbages in a town outside of Philly. Her poetry has appeared in Cleaver Magazine, Philadelphia Stories, The Shoutflower, Hot Pink Magazine and others, and is forthcoming in Plant-Human Quarterly and the anthology Queer Flora, Fauna, Funga, edited by Frances Cannon, Valiz Press. During the 2020 lockdown, she began making a series of stress doodles using cheap markers.

Sundress Publications selected her manuscript I Instruct My Toad How to Write Poetry as a as a semifinalist for its 2022 Chapbook Contest. In 2023, she received her MFA in poetry from Rutgers University Camden. In 2024, she was a Peter Taylor Fellow with the Kenyon Review Writing Workshops. She is a 2025 winner of the Mendelssohn Chorus of Philadelphia’s Joyful Abundance: Emerging Artist Commissioning Program. Amy Beth is a former Associate Artist with the Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice. Currently, she is Fence Magazine’s Steaming (online) visual poetry editor and serves on the board of Blue Stoop, where she helps with educational programming.

Get to know Amy Beth in a quick 5 Questions interview below.

Q1: How does your queer identity inform your work in the literary world?

For me, it might be the other way around: my writing gives me space to be my queerest self, like an antecedent river which, in geological time, erodes through newly rising mountains. It continues to flow through drastic changes in geography.

As an old woman in a long, loving relationship with a man I am usually unnoticed. The stereotype of struggling to get a bartender’s attention is real. Occasionally, I am strangely visible. The day after the 2016 election, I heard some cracked voices catcall, “dyke.” A group of middle-school boys had clocked me. Even though anyone who has read my published work can see the queer currents, my camouflage gives me the privilege of privacy but also means the sometimes lonely and disorienting experience of not being known. My therapist had been encouraging me to be more open about my identity and to live a more authentic life. I saw writing the application for this prize as a wonderful opportunity to work through those thoughts on paper. This prize gives unexpected visibility to a queer old hag.

Not surprisingly, I love words, so I’ve thought a lot about what to name my identity. Rather than bisexual, I like to think of myself as spanning borders, or as multi-genre. Since you study Gothic literature, London, you are probably familiar with Cohen’s essay “Monster Culture.” I like to think of myself as thesis seven, “The Monster Stands at the Threshold of Becoming.” I also like to call myself “hag” which is related to the word “hedge,” another border. I love the word “queer,” which I’ve heard is more often used by younger people than people my age. Originally, it meant strange or odd. Now it is a reclaimed pejorative with an expansive meaning. Expansive in a way that includes me. Expansive like love.

Queer writing spaces have long meant much to me. In 1981, my then girlfriend (to use the old terminology) and I went to the book launch for Lesbian Poetry, an Anthology edited by Elly Bulkin and Joan Larkin at the Arlington Street Church in Boston. Almost 45 years later I still vividly remember Pat Parker’s performance. More recently, I’ve hosted queer writers and worked in other ways to offer support. I find I benefit from being in expansive spaces as a writer and as a human. This community has given me a lens to see different ways of being in the world.

Q2: Are there any queer figures that inspire you/your work in this field?

In the late 1970’s, when I was what we used to call “a baby dyke,” I haunted the New Words Bookstore in Cambridge Mass. There, I bought books like Rubyfruit Jungle, The Dream of A Common Language, and This Bridge Called My Back.

Here are some brief thoughts on a handful of contemporary writers who inspire me.

- Claire Schwartz for her fruitful complexity, rigorous compassion, and nuance.

- Eric Sneathen for his intelligent use of the archives and poetic form.

- Gabrielle Calvocoressi for an unsentimental and complicated celebration of joy.

- Richard Siken’s new book feels important to me as an aging writer because he wrote it after a serious stroke. We can only write with the minds and bodies we have, and aging changes us.

- Samiya Bashir, the “poet-cartographer,” for her vibrant engagement with music, installations, and video.

Q3: What do you hope for the future of Queer Literature?

I wish for it to be uncensored and available to all readers, child and adult. And I’m afraid this is going to sound like a pageant contestant’s answer — but —I wish the same thing for queer literature that I wish for the world: a flourishing.

Q4: How does queer identity and poetry intertwine for you personally?

Recently I was listening to Edmund White talking to Terry Gross in a 1994 interview. He said, “you know I have the strange feeling that writing itself is somehow linked to homosexuality. … And it seems to me that there is something that – about writing itself, which is a way of at once participating in society but also looking at it from an enormous distance, of at once imitating the conventions of society while having a very jaundiced eye toward them.”

Poetic craft queers language and resists binaries: syntax is twisted, lines are broken, and layered meaning emerges. My sense is that fascism relies on binaries, us/them, worthy/unworthy, man/barefoot pregnant wife, human/nature. I think that’s why art and queerness are under attack. The complexity of navigating outsiderness is both a queer way and a writer’s way of being in the world. Poetry is an apt container for complexity. In my writing I search for forms that resist reductive thinking and false dichotomies.

Q5: What advice do you have for young queer poets entering the literary world? How can their work be a form a resistance and hope for the future?

I promise I will get to your lovely question about young writers, but first I have advice for all emerging poets, young and old: write the books Mom’s for Liberty etc. want to ban and fight to get them to the readers who need them. Write all the stories and poems that are important to you. Jane Miller’s lines come to mind. “May your desire always overcome//your need; your story that you have to tell,/enchanting, mutable, may it fill the world.” Use your full human imagination; your writing doesn’t have to be an empathy machine. People who disturb or disgust us are as worthy of compassion and justice as people we feel for.

I also have advice for emerging queer old writers. Ageism is real but don’t let that deter you. Some of our experiences may feel far from younger readers’: menopause, memory loss, the physical disabilities of aging. We have important stories for both our peers and for younger readers.

And for young writers, I think if the lines of the poem by Judy Grahn, “Slowly: a plainsong from an older woman to a younger woman”, “are you not wine before you find me/in your own beaker?” If you are lucky, you too will grow old. You will lose agility, you will lose stamina, you will lose nouns. But you will have a wider store of experiences which can afford a new kind of wisdom. Have compassion for your future self and for us.

The J. Michael Samuel Prize honors emerging LGBTQ writers over the age of 50. This award is made possible by writer and philanthropist Chuck Forester, who created it out of the firmly held belief that “Writers who start late are just as good as other writers, it just took the buggers more time.” The prize will go to an unpublished LGBTQ writer over 50 working in any genre. The award includes a cash prize of $5,000.

Get to know the 2025 winner, Amy Beth Sisson, below.