The Jim Duggins Outstanding Mid-Career Novelist Prize honors LGBTQ-identified authors who have published multiple novels, built a strong reputation and following, and show promise to continue publishing high quality work for years to come. This award is made possible by the Horizons Foundation, and includes a cash prize of $5,000.

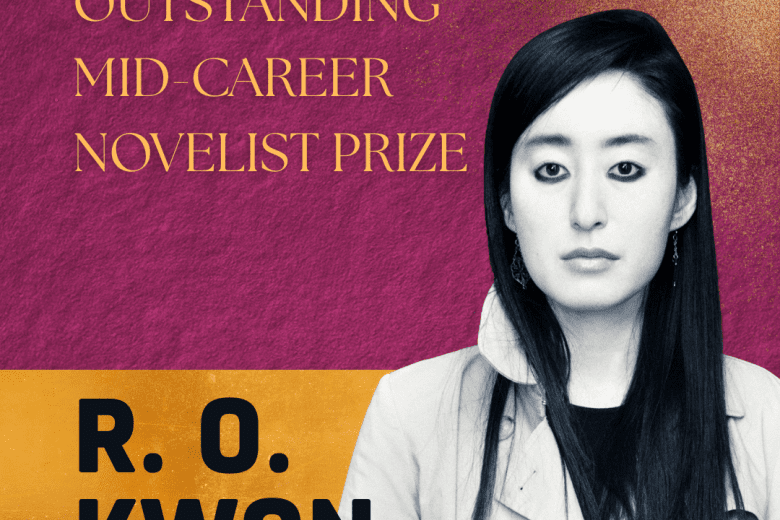

One of two winners of this year’s prize, R. O. Kwon is the author of the nationally bestselling novel Exhibit. Kwon’s bestselling first novel, The Incendiaries, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle John Leonard Award and the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Prize. Kwon coedited the bestselling Kink. Kwon’s books have been translated into seven languages and named a best book of the year by over forty publications. She has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Yaddo, and MacDowell. She is a 2025-2026 Visiting Fellow at the American Library in Paris. Born in Seoul, Kwon has lived most of her life in the United States.

We get to know Kwon in a quick 5 Questions interview below.

Q1: How does your queer identity inform your work in the literary world?

In every way possible. I grew up extremely Christian, so religious that, until I lost that faith, I intended to devote my life to God. In some ways, I’m always writing about the schism between that person I used to be and who I’ve since become, between what I was told I am and what I instead had to be. Over and over again in difficult times, as a queer, Korean, apostate woman, when I’ve felt like a plausible candidate for being one of the loneliest people in the world, literature has been there to remind me, Of course you’re not alone. Of course you’re not marked as being apart from humanity because of who you are and what you want. With the work I do both in my writing and as a person in literary communities, I want so much to offer back some of that life-giving fellowship.

Q2: Are there any queer figures that inspire you/your work in this field?

Multitudes! But today I’ll shout out some of the Korean writers whose books I admire who are also queer, as there still aren’t very many of us who are publicly out, and I love seeing our names together: Alexander Chee, Anton Hur, Franny Choi, Gina Chung, James Han Mattson, Jean Kyoung Frazier, Jinwoo Chong, Joseph Han, Patrick Cottrell, Sang Young Park and Willyce Kim.

Q3: What do you hope for the future of Queer Literature?

I want those of us who make and work in queer literature to be so manifold that there’s no counting us. I want it to be impossible to make a list, as I just did, of queer writers without inadvertently leaving hordes of us out. We’re on our way.

Q4: What does it mean for you to connect cultural and queer identities in your work?

Koreans tend to be so reticent about sexuality that, especially as a Korean woman, I’m really not supposed to give any indication in public that I’ve so much as thought about sexuality. Let alone wanted anything having to do with sexuality, let alone queer sexuality. Much of my writing has required that I continue to reckon with these pressures, and that I do everything I can with my work to try to break out of these inhibiting boxes.

Q5: How can exploring the concept of faith work to strengthen someone's queerness through literature?

I don’t think any god or gods who’d made us or even just cared about us could cast us aside and despise for being who we are. It doesn’t make sense. If I think of the faith I know best, Chrisitanity, this kind of casting aside doesn’t align with the imputed sayings of the Jesus I knew and thought I loved. And so, if you do belong to a section of a faith tradition that tells you you’re wrong to be who you are, then I’d gently encourage you to see if there are other paths for you. And literature is a very large place; it holds so many paths. As June Jordan said, our bodies aren’t wrong.