Dedicated to the memory of author and journalist Jim Duggins, the Duggins Prize for Outstanding Mid-Career Novelists honors LGBTQ-identified authors who have published multiple novels, built a strong reputation and following, and show promise to continue publishing high quality work for years to come. This award is made possible by the Horizons Foundation, and includes a cash prize of $5,000.

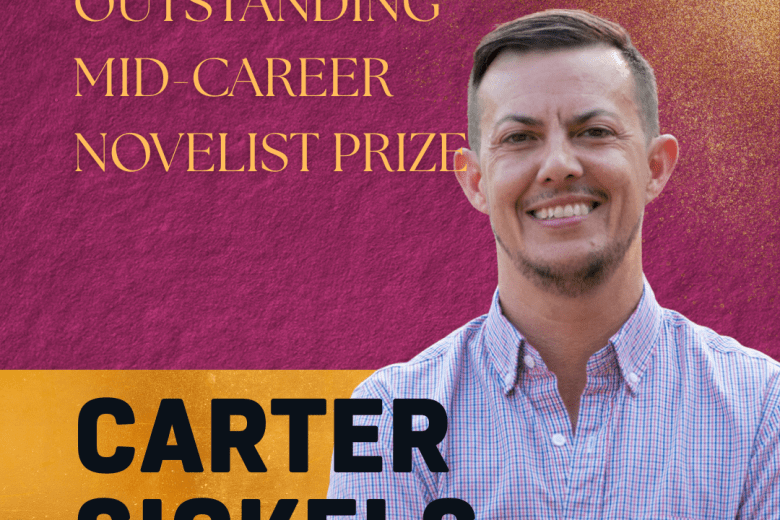

2025 prize winner Carter Sickels is the author of the novel The Prettiest Star, winner of the Ohioana Book Award in Fiction, the 2021 Southern Book Prize, and the Weatherford Award, and selected as a Kirkus Best Book of 2020 and a Best LGBT Book by O Magazine. His debut novel The Evening Hour (Bloomsbury, 2012) was adapted into a feature film that premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2020. His writing has appeared in various publications including The Kenyon Review, The Atlantic, Oxford American, Poets & Writers, and Guernica.

Carter was a 2024 finalist for the John Dos Passos Prize in Literature and the Granum Prize. He has received fellowships from MacDowell, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and VCCA. Carter is an assistant professor of creative writing at North Carolina State University.

We get to know Carter in a quick 5 Questions interview below.

Q1: How does your queer identity inform your work in the literary world?

I’m queer and trans, and that touches every part of my life, including my writing. Maybe especially my writing. I’m trying to shine a light on queer and trans people in rural America. Writing about queer and trans lives has always been important to me, but in the last few years, has grown more urgent. Even when I’m not writing specifically about queer characters, my perspective is queer, and I bring my way of seeing and understanding to my fiction. When I write, I feel at home with myself, though this is also sometimes difficult and feels vulnerable. Writing taps into this deep, creative, alive, true sense of self, and, for me, being trans evokes a similar experience and feeling. Transness, transitioning, like writing, is a process of discovery, emergence, revision, becoming and growing. It’s a gift. I’m grateful that I get to live on this earth as a trans man, and writing has given me way to share my voice.

Q2: Are there any queer figures that inspire you/your work in this field?

So many. An abundance! If I start to list them, I’ll inevitably and unintentionally leave out many names. I’m grateful to be a part of this shimmering, complex queer web of writers that crosses time and place. I would like to mention a couple of writers who had a profound influence on my writing: Dorothy Allison and Randall Kenan, both who wrote about rural places, both who left this earth too soon. I first read Randall’s collection Let the Dead Bury Their Dead in the ‘90s, and how he wrote from a multitude of perspectives, and with such empathy and nuance, stayed with me. I love this quote by Randall: “You have the power to define yourself—remember that power; take that control. It's like a superpower, really, to be whom you want to be, to do what you want to do, to fly where you want to fly.” Dorothy Allison was a literary hero and had a major impact on my writing. She wrote with tenderness and fierceness about queer people, poor people, queer sex and joy, violence, rural America. She never looked away from the hard stuff. She was a beautiful, courageous writer, and she had such a powerful presence: big-hearted, funny, charming. She taught me to write what scares you, breaking open hearts with words and truth. I aspire to her challenge, to write the “hard stories.”

Q3: What do you hope for the future of Queer Literature?

We all know the dire threats we are facing–authoritarianism and fascism, book bans that target queer and trans authors, rampant and unchecked AI. We’re watching as the government erases trans history and silences voices. It’s a bleak time, it’s dark. But I believe that making art is a radical act. It’s an act of resistance and empowerment. We write to create beauty, to push against and through borders and walls, to imagine and reimagine this world and new worlds. My hope is that trans and queer writers will find ways to keep telling our stories and sharing them. It’s important for people to see themselves represented in literature, and I believe to write about trans and queer people is to also make a claim that their lives have value. I hope that we continue to see an abundance of queer and trans literature that is daring, alive, and complex.

Q4: What advice do you have for young queer writers? How can creative writing serve as a form of resistance and strength in today’s political climate?

I think of what Audre Lorde said about our silences not protecting us, that the “transformation of silence into language and action is an act of self-revelation, and that always seems fraught with danger.” Writing is a tool for resistance and change, even in these dark times. Maybe especially in these dark times. I think for young queer writers, and for all of us, to remember where we come from, to remember what queers have fought for, how they’ve created art in the face of cruelty and repression, can also give us strength. As queer people, we carry the legacy of resistance and survival, and we need to tap into that history—Stonewall, ACT-UP. I want young queer writers to dream and imagine, and to feel fired up to tell the stories they want to tell, to discover and use their voices, and also to surround themselves, as much as they can, with queer community and supportive people. To take care of themselves and each other. Remember you’re not alone. I want young queer and trans people to know that a better world is possible and you are not alone.

Q5: What was the experience of seeing your literary work translated onto film like?

When you’re writing a novel, you don’t know if you’ll publish it, if anyone will read it – and it’s remarkable when the work leaves the private room of your mind and enters into the public’s imagination and hearts. Already, that’s a magical thing. So when I had the opportunity to watch these characters, the story, the fictional world I’d created live on in another art form, it was a thrilling experience. – The Evening Hour was published in 2012. When the film adaptation was shot in Harlan, Kentucky in 2018, I spent quite a bit of time at the shoot. It was a profound, sometimes surreal experience, seeing these actors inhabit the characters I’d created, these men performing men. I wrote the novel before I came out as trans, and while I was on set watching, I understood more about my need to write it—that spending all this time with my novel also gave me a way to examine my relationship to masculinity and rurality, and to imagine these men, and maybe some version of myself, into existence.