Hazel Jane Plante on Writing a Weird Queer Book

Author: Cooper Lee Bombardier

April 12, 2020

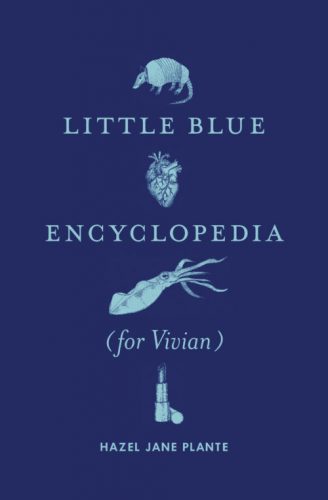

Of the sixty-three books I read in 2019, none were like Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) [a 2020 Lambda Literary Award Finalist] by Hazel Jane Plante. In fact, I’ve never read a book like this before. It is a meta-textual novel re-inscribed on the form of a fictitious encyclopedia through the lens of a pop culture tribute to a cult television show that does not exist.

Real pop cultural references intertwine with fictional ones, while the real ache of loss, the vibrancy of intimate friendships, and a quiet act of remembrance grounds this wonderful, weird, beautiful story. I was lucky to chat with the author about this book, constraint-based writing, trans creative collaboration, and the joys of writing pop culture into literature.

Hi Hazel, I am so excited to chat about your new book! What has the response been like so far?

I did launches in Vancouver, Burnaby, and Victoria. And I realized that, wow, I’m really loving reading from my book and people seem to be really into it. And I’ve had some great chats in person and online with folks. It’s been kinda astonishing to me that folks seem to like my strange little book so much.

I’d love to start off by asking you about the formal elements of Little Blue Encyclopedia. I was very struck by the layered narratives. The way the text merges actual pop culture references (in seemingly fictional usages) in with the fictional pop culture references of this world of Little Blue, a fictional television show, really kept me on my toes as a reader.

It seemed like this amazing undertaking for you as author to world-build a pop culture milieu from scratch, cataloguing it, and using it as a springboard not only for the narrator to reconstruct what Vivian loved, but also what she loved about Vivian. Can you talk a little bit about how you went about structuring these nested narratives?

This book took about nine years to write. Initially, it started as a book about a fictional TV series called Little Blue. I wanted to write a 33 1/3 style book about a piece of pop culture that didn’t exist. (I’ve been doing that kind of stuff for a while—writing book reviews for books that don’t exist, etc.—but I wanted to really dive in and focus on this one show.) For the uninitiated, 33 1/3 is a series of books about record albums. Each book in the series focuses on a specific album.

Then, I started working on a different project about the friendship between two trans women. Over time, those two things converged. One of the first things Metonymy Press asked me for was a list of the pop culture stuff in the book that was real because they blend so much with the fictional ones. As I started writing about both things, I realized that this shared TV series would be a good way to talk about the relationship between the narrator and Viv. I find people in my life are often watching and talking about TV series. It’s a thing we often share and spend time hanging out with those fictional characters. The structure of the book was fairly associative (in the first draft even) where things from the TV series would lead into moments from the relationship between the narrator and Viv.

I think more about pop culture than I should.

Oh, that sounds super cool. I loved the way that the encyclopedia entries become a lens through which the friendship can be reflected upon. What did a fictional television show, its narrative, and the narratives of its actors’ lives outside of the show bring to the project of this book that simply referencing an existing show might not have?

Ah, good question. For me, it allows me to explore and invent things. That’s kinda how my mind works. I’ll suddenly think about a show that I wish existed or a genre of music that would be interesting and write a thing about it. It sounds weird when I talk about it, but it’s just how I live in the world. Maybe it’s because I’ve had a longer relationship with art and pop culture than pretty much any individual person in my life. Art and pop culture are always there when I need them, y’know? I also recognize that I’m never gonna make a TV series or become a visual artist, but it’s super enjoyable and satisfying to write about TV series and visual art that doesn’t exist. Because it doesn’t exist, but if I describe it well then in the readers’ minds it kinda does exist.

That’s lovely. It sounds a bit of a triangulation between the pop culture that exists, that you wish would exist, and that you yourself make exist through this book.

Yep, that’s right. It also brought in the aspect of fandom that I think a lot of us have. Parts of the world are filtered through the things we love, whether it’s TV, music, art, etc.

Referencing a 100% known series might rein you in as a writer too much.

Yes, exactly! I love the idea behind the Museum of Jurassic Technology in L.A., which uses its exhibits to blur the line between things that actually exist (but sound too outlandish to be possible) and things that don’t exist (but are presented in a way that makes them sound like they possibly could exist), and some of what I do is an ode or a nod to that.

I’m glad you mention love, because in reading your book, I really felt a sense of love throughout it. How does your background as a librarian influence the encyclopedic structure of the book, if at all? As an author, do you come to the page with a predilection for cataloging and archiving?

Yep, I’m a librarian. It’s interesting because I did a launch in Victoria with the trans poet Ali Blythe and the event was hosted by Victoria’s Poet Laureate, John Barton. John mentioned during his introduction that he’s also a librarian and made some connections between my novel and librarianship, which was interesting because I didn’t really think too much about my job and the content in my book. I don’t really have a background in cataloguing or archiving, but I have always loved books that are doing something different formally. Pretty much all of my creative writing the past 10-15 years has been constraint-based. (I’m very influenced by the Oulipo writers, even though I don’t think their work is always successful.)

But I want to write works that use constraints organically, rather than having them be a stunt. I’m using constraints for myself because they force me to think differently. When the form of a book and its content work together it can be phenomenal. Not sure I did that, but I think the encyclopedia form works and grows organically from the content of the story.

Constraint-based work is super interesting to me too. I am in the middle of teaching an online writing course on constraint-based and hybrid form texts—next time I’d like to include your work for the students to read, too. I appreciate how constraints help to impose a structure in advance and how that changes the thinking process. You were successful, I’d say, in allowing constraints to be organic and flow well as a narrative in your book.

I saw that you were teaching that course and I thought it’s such an exciting, interesting way to approach literature. So much literature is actually constraint-based, even if it doesn’t seem to be. I came to writing as a poet and poetry is what I wrote for several years. That’s so nice to hear about the flow of the narrative! I as well as this quirky TV series. I’ve had so many people say to me, I wish Little Blue was a real TV show—me too! There are quite a few allusions or references to poems/poets in here, many of them pretty well masked, but if folks are really into poetry, they might be like, oh, that’s an allusion to bill bissett or Phyllis Webb, etc.

I can definitely see the poetic influence in your prose writing here. In the B section of the encyclopedia, you reference some punk lyrics as a palimpsest, and the children’s encyclopedia in which the narrator writes the Little Blue entries into in tribute to Vivian is also a palimpsest. Do you consider the form of this book as a sort of palimpsest, too?

Yeah, I definitely think there’s some palimpsest-like layering going on in this book. I’m really interested in how we write over things and how what used to be there still shines through. I was recently in Berlin and it was amazing to see how well designers had repurposed old structures and let the old structure show through—swimming pools turned into bars, laundromats turned into restaurants, public toilets turned into hamburger joints. I really wanted a book that included images of all those repurposed spaces, but I don’t think that book exists. Yet.

Next project for you, perhaps?

If I were a better photographer, fuck yes! I’d really love for someone to do that project, though. Please do that project, somebody. I want a gorgeous book that captures all those spaces.

I’m good at thinking up projects, but the follow-through takes much longer. That’s partly why I folded so many little ideas into this book: I’ll never have time to finish all the things I wanna do, so let’s just pretend they exist!

The fact that Vivian has died looms large throughout the book, and yet it is engaged with quietly: the circumstances of Vivian’s death is less dramatized than the emotional resonance of grief for those she left behind. The reader is told that she did not take her own life, but how she died is left for the reader to imagine. I read this as both a literary move and as a political act. Will you talk about how you conceived of rendering the narrator, who might be named Zelda, grief in losing Vivian, and why you chose to not state overtly how she died?

Yes, I’d agree 100% with your suggestion that how Viv’s death is described is both a literary move and a political act. The deaths of trans women (particularly trans women of colour) are so often reduced to their names, and where and how they died. And this sense of martyrdom is maddening because it is so reductive and because these were women who were just trying to live their lives. It’s much more important to know who someone was, who and what they loved. When it came to describing how Viv died, I actually didn’t include anything about it in my earliest drafts. When people started to read it, they seemed to assume that Viv killed herself. At some point, I decided that I really needed to push against this idea because she had dark moments, but she didn’t kill herself. I started imagining a poem that the narrator was reading and then I started writing it. It was about trying to keep trans people alive. It came out of revisiting Phyllis Webb’s “To My Friends Who Have Also Considered Suicide,” which is a brilliant, powerful poem, but which made me angry when I re-read it because many folks in my life struggle to stay here and I want them to stay alive. So, a response poem tumbled out of me: “To My Trans Friends Who Have Also Considered Suicide.” And I realized that after including that poem in the book that I needed to talk about the fact that Viv didn’t kill herself.

It’s interesting that you call the narrator Zelda because I’ve read reviews that say “unnamed narrator” or had people at readings ask me if that’s her name. It’s another one of those things that’s up for grabs, even though I think there’s evidence that that’s likely her name.

Thank you for saying all of that. I really appreciate the push back against this idea that as trans people we loom larger in our deaths than in our lives.

The narrator sees Vivian as a mentor, as someone who took her under a wing, though it is unclear if Vivian saw herself in this role. Though I believe that they are quite common, exploration of this kind of trans mentor/friend relationship doesn’t appear so often in the literary works of trans folks. I feel like there is so often a pressure on trans writers to make work speaking to the non-trans reader, to come across as “the only one,” positioning the trans narrator as a lone presence on a hero’s journey toward cis acceptance. The solo trans person becomes a mirror to the non-trans reader. Maybe these are the stories that seem prevalent because they appeal to cis audiences and so publishers see a market for them. Your book rejects this pattern beautifully. In reality, trans people gravitate toward each other and have other trans people in their lives. We seek advice and friendship and mentorship from those who’ve come before us. I know that this is not really a question, but this was a powerful element in your book for me as a reader and I am hoping you might speak to it.

I’m really, really glad that came across in the book. Yeah, most of the friends the narrator has are trans, and there are passing references to a support group she used to be in, etc. Yeah, I’m not sure Viv saw herself as a mentor, though I think she likely did. But I doubt she would have described the narrator as her best friend. I’ve had a few trans folks tell me how much they liked the relationship dynamics in the book, which feel like the kind of messy relationships that often occur between trans and queer folks. I can say that I really didn’t want to write a book for cis readers. No offence, but they already have a lot of books. Trans folks need to see more complex, flawed, smart, and funny trans characters. We so fucking need that.

Oh my god, yes. Preach.

What are you working on now? What comes next?

I’m pretty cagey about talking about current projects, but I’ll say that this novel took several years to write and I mostly wanna collaborate on writing and music projects with other folks (especially trans folks) who I like spending time with, who I think are doing great work, and who I think would be fun to work with. That idea is so exciting to me right now.

Is there a question you wish someone would ask you about the book but hasn’t yet?

Hmm. I sorta wish people would ask me about some of the really weird stuff in there. At a reading a couple days ago, I literally asked someone I was chatting with who’s trans and who really liked my book, “There’s some weird stuff in there, right?” They were like, oh, yeah, definitely. But I’ve been amazed at how many straight, cis folks seem to really like my book.

It reminds me of something Joe Strummer said when a friend told him how much his grandma liked London Calling. If memory serves, Strummer wondered aloud if he should have made a more offensive album. This was very much the book that I wanted to publish (and with the publisher who I most wanted to work with—tiny-but-mighty Metonymy Press), so I’m happy if straight, cis people (and their grandmas!) like my book. It’s a pretty weird, queer little book that I genuinely thought would only resonate with trans readers.