Will We Survive the 1980s? A Snapshot of a Gay Cultural Milieu

Author: Edit Team

December 18, 2019

The recently released Beautiful Aliens: A Steve Abbott Reader (Nightboat Books) offers an illuminating survey of the work of beloved Bay Area writer Steve Abbott (1943–1992). Abbott, a poet, critic, editor, and novelist, was not only a champion of the literary arts, but he was also a thoughtful cultural critic. In the following excerpt, originally written in the late 80s, Abbott offers a highly personal take on the late-century social milieu and unknowingly provides insight into our current political moment.

WILL WE SURVIVE THE 80’s

Never has evaluating the present and future of gay politics and culture been so problematic.

The 1986 Supreme Court ruling (Bowers v. Hardwick) was a setback, but AIDS has become our greatest challenge. And yet we‘ve made great gains over the past 20 years. Before the Stonewall Riots in 1969, our existence was virtually unspeakable. The phrase “corruption of morals past all expression”—used by European colonists about Native American sexual practices—was America’s prevalent attitude toward homosexuality. More liberal, educated citizens merely considered us “sick.” So out of fear we hid—from America, from our families, from ourselves.

Coming Out

The first step in our liberation was “coming out.” Even before Stonewall, a brave handful of individuals had done so: poets such as Robert Duncan and Allen Ginsberg, activists such as Harry Hay, Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings. But after 1969, this process mushroomed. Antiwar activists paved the way saying “Make love, not war,” and hippies by saying “Do your own thing.” Feminists challenged sex roles. New underground and gay newspapers proclaimed: “Gay is good.” Gay bars played the role for us that black churches played for the black civil rights movement. They were our meeting places.

I still recall the first gay bar I attended in Atlanta, Chuck‘s Rathskeller. On weekends, over 1,000 gays and lesbians attended. I never imagined our numbers were so great, and the thrill I felt in seeing so many same-sex couples dancing together cannot be described.

But coming out publically was a different matter. Friends and jobs could be lost. So the first wave of us who came out were political radicals. We‘d marched for other causes; now we marched for our own. At first the older “hidden” gay community felt threatened, but our numbers grew. And as we came out, America noticed. First in curiosity, then in growing respect.

Now national TV networks, magazines, and newspapers discuss us on a daily basis, often in regard to AIDS but in other contexts too. ABC News recently did a segment on parents of gays and Cleve Jones was its “Person of the Week” when the NAMES Project went to Washington. Gay leaders, such as Ken Maley, have been profiled in the Examiner, and Issan Dorsey, of the Hartford Street Zen Center, in The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town.” Openly gay journalists, such as Randy Shilts and Edward Guthman, have won awards for their writing in the Chronicle.

We’ve won numerous political battles as well. In 1974, the American Psychiatric Association decided we weren‘t mentally ill. During the course of the 70s, half of the states eliminated sodomy statutes and many large cities included us under civil rights protections. In the 80s, gays in professions and academia have come out as well. Dear Abby and Ann Landers now advise Middle America that our sexual orientation is a valid option.

Culturally we’ve done well too. Never have there been so many good books, plays, and films on the gay and lesbian experience: witness the increasing size of our film festivals, major studio films featuring gay love stories, and Newsweek featuring gay writers in its book section. Gay bands, choruses, square dancers, and performance artists tour the country regularly. Gay playwrights, such as Harvey Fierstein and Harry Kondoleon, have been praised in The New York Times. And if Lou Reed felt a need to tone down his “walk on the wild side,” many openly gay pop singers from Sylvester to Morrissey remain popular.

The Impact of AIDS

But while we defeated the Briggs and LaRouche initiatives and survived Anita Bryant and Jerry Falwell, AIDS has taken a terrible toll. In 1981, 225 cases of AIDS were reported in America; by the spring of 1983, 1,400 cases; by summer of 1985, 15,000 cases; and two years later, 40,000 cases.[1] We‘ve lost many of our most brilliant political leaders. America has lost many of its most promising and prominent cultural figures. Meanwhile, with the exception of Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, the Reagan administration has just twiddled its thumbs. Let us call this cruel indifference by its right name—intentional genocide.

Now the upwardly spiraling statistics—450,000 American cases of AIDS projected by 1993—have goaded even Reagan’s conservative AIDS commission to call for major action. It’s not, I suspect, that they care about the lives of gay people; they’re just worried about the coming insurance and health care crunch. I read recently that one in every 152 San Franciscans has AIDS; by 1993 it will be one in every 42.[2]

Now the upwardly spiraling statistics—450,000 American cases of AIDS projected by 1993—have goaded even Reagan’s conservative AIDS commission to call for major action. It’s not, I suspect, that they care about the lives of gay people; they’re just worried about the coming insurance and health care crunch. I read recently that one in every 152 San Franciscans has AIDS; by 1993 it will be one in every 42.[2]

No cure appears to be in sight. What this means is that in five to seven years the gay community may be depleted by three-fourths its present size. Can anything save us from political and cultural extinction?

San Francisco’s gays won political power only because we became a large, well-organized voting block. What will happen when this voting power shrinks? Culturally too, our films, plays, novels and music sprang to national attention only because a large core gay audience was hungry to hear its stories told. By 1995 this voting power, this cultural audience, this political and cultural leadership, will be largely gone.

Our history, even when we’ve been strong and well-organized, has not always been happy. The first Christian emperor of Rome, Justinian, believed we caused earthquakes, and massacred us as a matter of state policy. During the Inquisition, we were the “faggots” used to burn “witches.” Hitler crushed a rising gay movement in Germany and sent 200,000 of us to death in concentration camps. In the past year, sparked partly by AIDS hysteria, antigay violence has risen 42% in America.[3]

Nor does this persecution come only from ignorant street thugs or emotionally unstable assassins like Dan White. In 1984, two prominent American poets—Ed Dorn and Tom Clark, the latter who now teaches at New College and reviews books for the Chronicle—published a satirical “AIDS Awards for Poetic Idiocy” in Dorn’s literary newspaper, Rolling Stock. In this, they join intellectual fag-bashers such as William F. Buckley, William Gass, Midge Decter, and Norman Podhoretz. They mock us as we die, knowing full well that antigay humor leads to antigay violence. Language and ideas can kill just as surely as viruses, clubs, and guns. Indeed, there’s more of a connection here than is generally realized.

Language, Capitalism and Disease

What feminism, gay liberation, and the philosophical research of Michel Foucault contributed to an understanding of sexual identity is this: they showed us that sexuality is not simply “natural” as Aristotle thought, not just a biological urge as Freud thought, but a social construct that evolved through history to enable power to regulate and define social behavior and thought at both the level of individuals and groups.

Overthrowing earlier social formations, the ideology of heterosexuality used sexism to subjugate women and homophobia to keep this system intact. Industrial capitalism (ownership of other’s labors, bodies, and sexuality) embraced this ideology even more fervently than did feudalism. The body was now considered a little machine to do power’s bidding. Nor did Marxism fundamentally challenge this ideology, since its main focus was economic.

But facing successive crises, postindustrial capitalism (like a clever virus) mutated. It incited a division of sexualities so as to internalize, intensify, and yet disguise its control. Now power could be almost liquid in the games it played. It could make us feel free even though the only choices we were allowed to make were increasingly superficial, even though we were really only free to participate in what Guy Debord called the “society of the spectacle” (welcome to the spectacular abundance but increased manipulation and impoverishment of “TV reality”). Capitalism could even encourage us to be gay while twisting tighter the screws of internalized homophobia (e.g., good to be gay only if young, pretty, rich, hip—in short, a good consumer).

Non-Western medicine (that of the Chinese, Sufi, native peoples, etc.) has long recognized that physical disease results from spiritual disharmony. To obsess about sex, for instance, throws one out of balance. To do this and feel guilty increases stress, causing internal conflict and eventually mental or physical collapse.

Consider the new diseases that have come to flourish under postindustrial capitalism: cancer, heart disease, AIDS, drug and alcohol addiction. All are caused by excessive stress, bad diet, or a toxic external environment. The first two are epidemic only in advanced capitalist countries. In fact, cancer—in which some body cells go out of control in their desire to overwhelm and dominate surrounding cells—might be seen as a miniature paradigm of capitalism. Addictive behavior, on the other hand, is a response to feeling psychically helpless in a hostile world that one can’t, but nonetheless tries to, control.

And AIDS attacks the immune system, that part of the body that preserves the body’s identity and repels foreign invaders. If one is attacked, a healthy response would be to fight off the attacker. But if one has internalized the oppression (as in internalized racism or homophobia), if one consciously or unconsciously agrees, “Yes, I am sick. Yes, I am bad,” then one either tries to escape this realization via excessive drug and alcohol use, or else one simply begins to internally self-destruct.

Fighting Back

Our community has always been cross-class, cross-race and cross-gender, and we have suffered divisions based on these differences. But whenever we were attacked—by the Briggs initiative, for instance—we came together and fought back. In many ways we are doing this now. Gays and lesbians are working more closely together on a personal level, on new magazines such as Out/Look, and on the recent March on Washington.

In the Bay Area especially, where a strong support network already existed, we have done heroically well in caring for each other. We have worked in Shanti, in the AIDS Foundation, in setting up hospices and, perhaps most brilliantly and creatively of all, in the NAMES Project. The NAMES Project Quilt showed America, the world, and ourselves how deeply and beautifully we care for each other—not just in the sense of eros but in the even deeper and more spiritual sense of agape. The NAMES Quilt stands as one of the most glorious accomplishments of our history. However, the division between sick and well, and the problem of how to preserve our culture and community cannot be bridged by a quilt alone, no matter how large it may grow.

The majority of those uninfected in our male population are young. And youth—struggling to build its own identity, to find housing and work—is not renowned for compassion. Playful, energetic and lustful, yes; patient, wise and loving, no. Moreover, youth wishes to imagine it can live forever and generally seeks to avoid such depressing topics as illness and death. I could cite many notable exceptions—indeed, gay youth today are probably more serious than ever before—but, overall, we cannot expect youth to be anything but what it is.

So “Boy Clubs” are flourishing with all the happy frivolousness that the phrase implies—dress-up, go-go dancers, moderate drinking and drug taking. And while a new seriousness is evident artistically and spiritually, political maturity is often lacking. Rights so painfully won are often taken for granted.

The generation that would normally provide education and leadership to gay youth has largely turned inward. Some are providing daily health care to lovers and friends, care not provided by society at large. Others have admirably devoted themselves to anonymous 12-step programs such as AA, NA, and Al-Anon to recover from their own addictive excesses of the past. Still others have turned away from political and social concerns for an inward personal and spiritual evaluation.

In some ways this turning inward may be positive, a leadership of quiet example—not who’s on stage but what’s on the page. Several marvelous books on what it means to be gay have resulted: Judy Grahn’s Another Mother Tongue, Edmund White’s The Beautiful Room Is Empty, Robert Glück’s Jack The Modernist, and Gay Spirit edited by Mark Thompson, to name a few.

Many publications within the gay media and organizations such as the Gay Sierrans, the San Francisco Gay and Lesbian Historical Society, Black and White Men Together, and Act Up also play a crucial leadership role. Gay playwrights and filmmakers, in particular, have taken the lead in teaching us how to cope with AIDS and with our grief. But gay leadership today is not so simple as it was 10 or 20 years ago. A dollop of good cheer, or burning anger, may be useful but it’s not enough. Who can provide easy answers if there aren’t any?

Revisioning Who We Are

To fight AIDS and the conditions that threaten us, we need more than scientific research, more than money, more than leadership. We need to rethink America’s spiritual, political, social, and cultural systems at the most fundamental root level. How do we use power? How do we use language? It is clear that what we are doing now—as bosses and workers, as men and women, as gays and straights, as whites and non- whites—is killing us all. And as we project these attitudes onto other species and towards the Earth’s ecological system, we are jeopardizing our very planet. I would argue that today we can no longer afford to see anything—not even “gay liberation” or our survival—as a separate issue needing a separate cultural, political or spiritual agenda.

This does not mean I intend to renounce my sexual orientation, far from it. Even in times of sadness or loneliness, it remains my greatest source of strength and joy. But if my sexuality is a social construct, I can change how I think about and act on it.

“Gay is good” doesn’t have to mean what I used to think—that I need a lot of sex or a lover to be happy. Nor need it mean the opposite—stoic celibacy. It can also apply to how I center and balance myself, how I choose and nurture friendships, how I support my community. And when I consider or have sex, can I change how I think about it—to admire, share, and enjoy beauty without trying to use, own, or consume it? Pleasure is good but we are not objects. And contrary to what fashion, ads and some songs suggest, neither are we just images or toys.

In work and play, how can I free myself from the hype of competitive stress? Can I learn to accept and find joy in the present moment, even when it’s not what I might prefer? Can I continue to take risks, to redefine myself? Can I wake up from sexism, racism, ageism, and careerism without becoming obsessed about being “politically correct?” Can I set and fulfill goals, while still allowing spontaneity? In short, can I take my energy glue out of the worry/fear/consumer trap?

These are some of my questions. What are yours? What do you hope for? Each of us must take more responsibility for our own lives as well as for our collective life. Instead of doomsaying, we must participate more fully in social and cultural institutions, and change them—as indeed, we are. We have achieved what we have because we dared to dream and to risk acting on those dreams. This must remain our commitment.

Sitting with My Friend

AIDS is neither a curse nor a blessing; it just is. I see its inexorable progression in a 24-year old friend whom I’ve been sitting with every Friday for the past nine months. I got to know J.D. in a healing workshop. He came up to me one night and gave me a hug because, he said, he just felt I needed one.

J.D. is such a beautiful person I found it hard to believe at first that he was sick. But last fall he became bedridden. I wasn’t sure if I could cope with helping care for him—I’m not trained as a nurse—but it was just something that needed doing, so I did it. I felt awkward at first but he encouraged and gave me confidence.

Words can’t tell what I’ve learned from J.D.—about myself, about life. Sitting with him every Friday and watching his courage and dignity in the face of this disease has been one of the most intimate, inspiring experiences of my life. It’s not always been easy, certainly—not for J.D., his lover, his parents, or for any of us—but it’s been real. Often we’ve sat for hours together and said nothing, yet said more than most people ever do. His hands flutter like butterflies. He sometimes suffers delusions. But don’t we all?

Because I’m antibody positive, I know I may be in J.D.‘s position myself someday—still alive but fading, with little control of body or mind. We all die differently, just as we all live differently. I don’t know what it will be like for me but I’m no longer afraid. I still feel angry, frustrated, or self-pitying sometimes—often over the most trivial incidents—but when I’m with J.D. these feelings drop away. And I’m filled with such a profound gratitude to be alive, to be gay and to have the friends I have and have had, that I cannot explain it.

It’s a simple fact that someday all of us will die. Maybe our entire planet will. But I also know now, more deeply than ever, that our lives, our culture and our world are too beautiful to throw away.

[1]D’Emilio, John and Estelle Freedman, “The Contemporary Political Crisis,” Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America, Harper & Row, New York, 1988, p. 354.

[2] Jeffrey Amory, director of US Public Health Department’s AIDS Office, testifying to US Senate’s Governmental Affairs Subcommittee, San Francisco Examiner, June 7, 1988, p. A-18.

[3]As reported by the National Gay/Lesbian Task Force’s Antiviolence Project (1987 study) San Francisco Examiner, June 7, 1988.

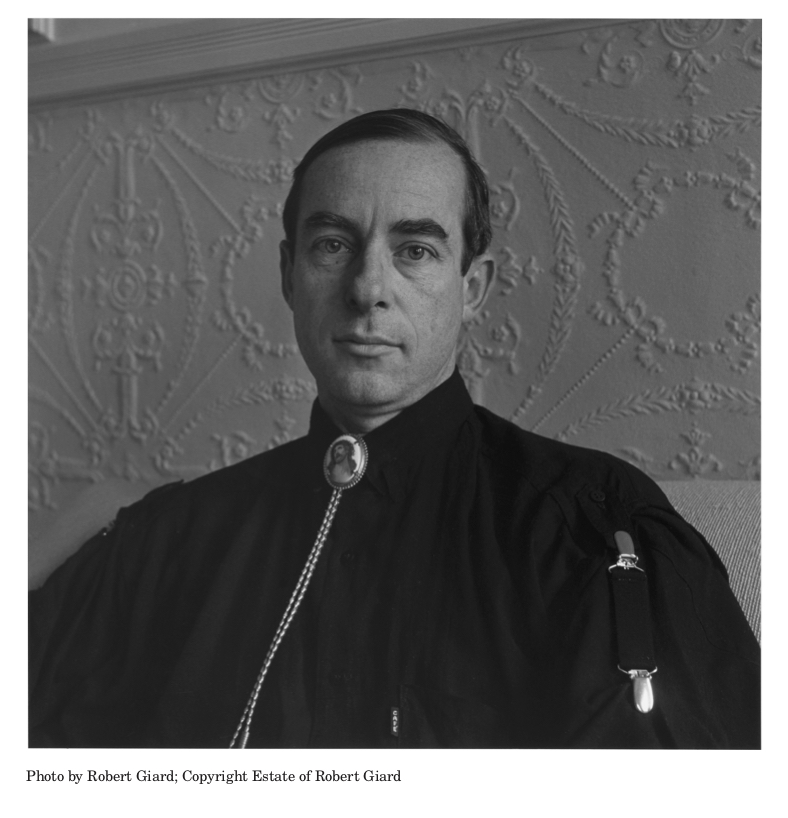

Featured Image: Steve Abbot/Photo Credit: Robert Giard