Colm Tóibín on the Casual Brilliance of Edmund White

Author: Edit Team

July 17, 2019

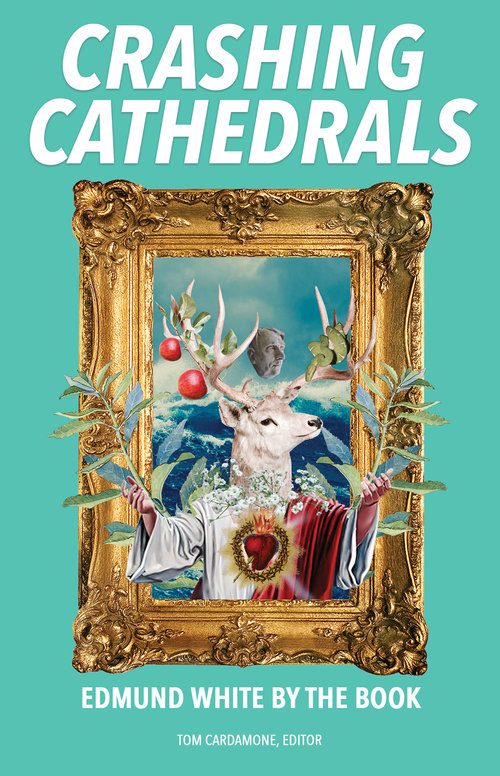

In April, Itna Press released Crashing Cathedrals: Edmund White by the Book. Edited by Tom Cardamone, this compendium of essays, from a vast array of noted queer writers, offers personal reflections and insightful literary analysis on each of Edmund White’s books.

The below excerpted essay, written by author Colm Tóibín, is a deep dive into White’s celebrated novel The Married Man.

*

They were ghosts who’d come back to haunt their former lives; some higher dispensation allowed them to inhabit this old apartment for just five days, but it, too, was ghostly— shabby without its soft lamps and bohemian throws tossed over the mammoth metal heater that no longer worked. The apartment was dusty and resonant. Given how small the rooms were, the resonance sounded off, as though they were in the antechambers to a mammoth cave. The windows were curtainless, the worn carpet denuded of the two sumptuous silk rugs Austin had brought back from a holiday in Istanbul, the kitchen empty of its dishes and cutlery.

—From The Married Man

It is easy to misread Edmund White’s major novels A Boy’s Own Story (1982), The Beautiful Room is Empty (1988), The Farewell Symphony (1998) and The Married Man (2000) simply as autobiography thinly disguised as fiction, or indeed merely fiction which uses the facts of the life of the author, and the texture of that life, as the basis of the narrative, and does nothing else. Such a reading ignores the stylistic differences between the four books themselves, and pays no attention to each of them as exercises in pure style, each with its own systems and cadences mirroring differences in the sensibilities that they portray and the worlds they dramatize.

Nonetheless, it is hard not to feel that the further apart the life of Edmund White is kept from the novels he has written the purer and more serious the fiction becomes. This is especially true with what I consider his finest novel, The Married Man. In this novel White dramatizes with considerable subtlety the conflict between two ideas, allowing his characters to embody these ideas and remain also filled with unpredictable and sensuously imagined life. The first idea is that the personal is political (“which,” White wrote in 2002, “may be America’s most salient contribution to the armamentarium of progressive politics”), that proposes before you join a demonstration for human rights you put your own house in order, that honesty and integrity in the domestic sphere are as important as large questions of public morality. This idea became important for gay men in the United States from the early 1970s onwards.

In The Married Man Austin Smith arrives in France all the more in possession of this idea because he is almost unaware of it. He meets Julien, a younger man, who is French, who believes, again almost unwittingly, in another idea: that the self is there to be invented, that evasion and deceit are fundamental to survival, and that full honesty in either the public or private sphere would make life impossible.

Both men have their charms, and they enjoy each other; but they come tragically to misunderstand each other, or at least Austin does Julien, as much as any Jamesian hero or heroine a hundred years earlier came to misread elegance for morality, or came to see style and presumed it contained goodness.

The less you know about the author Edmund White the more intense and rich the book The Married Man becomes, the more heart-breaking the final episodes, and the more complete the novel seems in its subtle moral shape. It is a work of art rather than another volume of autobiography.

Edmund White is in full possession of a prose style that is deceptive in how it functions. His writing can feel like conversation or someone thinking clearly and honestly or taking you slowly and effortlessly into his confidence. The cadences of his writing are close to the rhythms of speaking, but there is also a mannered tone buried in the phrasing, which moves the diction to a level above the casual and the conversational.

White’s style, however, depends on a sort of candor, a strange knowing mixture of innocence and fascination with stripping the secrecy away from the story as it unfolds. As a writer of personal essays and biographies as well as novels, he has, it seems, no interest in hiding the sources of his inspiration or shrouding himself or anyone else in mystery. Since he was brought up in a time when many gay men kept their sexuality a secret, secrecy has little allure for him. He likes revelation, and the pleasure he takes in it adds great energy to the narratives he creates both in biography and in fiction. As a good Midwestern American, he believes in plain, personal honesty; as a writer steeped in French life and literature he also loves intrigue, gossip, the spilling of well cooked and richly spiced beans.

It is possible to read The Married Man as a re-imagining a hundred years later of Henry James’s The Ambassadors. In James’s novel Lambert Strether comes to Paris in middle age with a clear task, which is to return the young Chad Newsome, who has been idling in Paris, to his mother in America. Slowly, Strether himself begins to idle in the city, allowing its beauty and allure to distract him from being single-minded. Slowly, too, he begins to spend time with Chad and his friends, attending a party in Chad’s apartment and entering into the elegant and easy-mannered social life that Chad has created for himself in the city.

The Ambassadors is a paean to Paris itself, its street life, its social life, its architecture, its manners. Strether’s first walk in the streets of Paris, his first taking in of the city’s sensations, make clear that he is an American open to allure in the same way as Austin Smith in The Married Man is beguiled by the view from the windows of his apartment on the Île Saint-Louis. Smith could “lie in bed and look at the church’s slate-covered roof, pitched sharply, and a huge volute of stone almost ten feet in circumference that had been carved to resemble a spiral closing in on itself and slightly squashed at the top.”

Both Strether and Smith operate in a world of belles lettres, Strether as the editor of a review and Smith as a writer about 18th century French furniture, among other matters. This means they can be free to travel and move, to take their time, not to need, as other men do, to go to work each day and stay at work until day wanes. They are both, for the purpose of the novels, men of leisure. Neither is rich, but neither is especially preoccupied by money. Both are middle-aged, and in The Ambassadors and The Married Man, both become interested in people younger than themselves who seem to possess an energy, a vitality and an innocence which fascinates both men.

Both Strether and Smith operate in a world of belles lettres, Strether as the editor of a review and Smith as a writer about 18th century French furniture, among other matters. This means they can be free to travel and move, to take their time, not to need, as other men do, to go to work each day and stay at work until day wanes. They are both, for the purpose of the novels, men of leisure. Neither is rich, but neither is especially preoccupied by money. Both are middle-aged, and in The Ambassadors and The Married Man, both become interested in people younger than themselves who seem to possess an energy, a vitality and an innocence which fascinates both men.

In Chapters Three and Four of The Married Man, we see Austin Smith’s social world. Smith at this point is forty-nine. “Austin had invited six friends who were in their early thirties… The men were gay and the women straight and everyone loved to drink and joke and exchange stories and have a good time till one in the morning.” In the next chapter he will attend the salon of the rich socialite Henry McVay and gossip familiarly with his host. Early in The Ambassadors, we see the social world of Chad Newsome in which Strether has been included, including a relaxed and elegant social event at Chad’s own apartment and also a party at the studio of the famous sculptor Gloriani.

Strether and Smith are both men alone, socially secure enough to be included in many conversations, socially uneasy enough to notice everything, their noticing offering a richness to the texture of both novels.

“You could deal,” Strether thought when he first saw Chad in Paris, “with a man as himself—you couldn’t deal with him as somebody else.” Both Strether and Smith see the world as it presents itself to them; they like what they see, and this pleasure taken in Paris and its denizens gives them both a sort of fictional density and complexity. It also allows them both, or induces them, to believe what they hear. Enjoying Paris has made them both even more innocent than they might be in America. Thus when Little Bilham, who is a friend of Chad’s, tells Strether that Chad’s relationship with the Vionnet mother and daughter is “a virtuous attachment,” he takes him at his word. So, too, when Austin Smith meets a young Frenchman in a gym, he is inclined also to believe what the young man says.

“He was moving verily in a strange air and on ground not of the firmest,” James wrote of Strether. What Strether was seeking was experience, the tender taste of life. In not seeking wisdom, he found knowledge instead, and he had no idea what to do with knowledge. He was ready to notice things, and wanted to notice more. As he moved slowly away from the rigidities of his background, he discovered, as did Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady, that his only weapon was innocence, an innocence which became more exquisite as the novel proceeded, an innocence which was no use to him in this old world into which he had ventured.

When Austin asks Julien, the young man he had met at the gym, a number of basic questions, he finds Julien slippery and evasive. Like Strether, Austin’s only weapon is his innocence, but his innocence puts him at a loss. “Austin felt he was out of his depth, facing an older culture than his own, one much harder to sum up. His own assumptions struck him as shoddy. He was sorry he’d revealed his West Village smugness; he had belonged to a New York gay world for twenty years and it had left him with too many ready answers.”

As Julien becomes Austin’s lover, he is all ambiguity, all French sophistication. Simple questions do not interest him. The story of his life that he tells is one of pain and loss and cruelty, thus making Austin all the more certain that what he is in need of now is simple comfort, ease, trust. Since he, as a younger man, is an object of intense desire for Austin who believes that this may be his last chance for love, then the question of full disclosure of Austin’s HIV status is pressing for Austin. He discusses this with a French friend: ‘“I don’t dare seduce him before explaining to him about being seropositive. Or what would you say?’ He was half-hoping for some superior French worldliness that would get him off the moral hook.”

Just as in The Ambassadors, signs are given in The Married Man that what the protagonist is facing is not old-world sophistication but old-fashioned duplicity. Strether and Smith fail to see clearly because they are dazzled by youth and by beauty, and they are in a foreign country, but also because they are being most cleverly and beguilingly deceived. Edmund White manages in the most subtle way to make the most personal book into the most political as post-Stonewall candor comes face to face with post-Vichy ambiguity, with what he calls Julien’s “dandified distance from all moral questions.”

As Austin makes himself easy to read, Julien adds mask after mask. It would be easy for Edmund White to make Julien’s unmasking into a large morality scene, and it is a credit to his artistry that he slowly allows us instead to see Julien as fearful and desperate as much as mendacious and manipulative.

As The Married Man moves to America, it takes its bearings once more from Henry James, but this time from the tone of condescension and barely-managed contempt which emerges in some of the pages of James’s book The American Scene (1907). For example, James, who had become a connoisseur of European beauty, disliked the new mansions perched overlooking the ocean at Newport, Rhode Island: “They look queer and conscious and lumpish—some of them, as with the air of the brandished proboscis, really grotesque—while their averted owners, roused from a witless dream, wonder what in the world is to be done with them. The answer to which, I think, can only be that there is nothing to be done, nothing but to let them stand there always, vast and blank, for reminder to those concerned of the prohibited degree of witlessness, and of the peculiarly awkward vengeances of affronted proportion and discretion.”

Austin Smith, also returned after his own years in Europe, is equally affronted by Providence, Rhode Island. “Here he was in this cold, empty city with its boxy houses, their windows glowing dimly at night, this city with its abandoned, windswept down- town with the dark dangerous woods across the street… The house with its smell of mildew, its plastic poppies, its framed Polish lace… It was an outpost of an alien culture.”

Alongside this dramatization of trans-Atlantic distinctions, delights and disapprovals, The Married Man begins to chart the slow physical disintegration of Julien from AIDS. Edmund White has managed with care to make us see and feel how much Julien fascinates Austin, and make us believe also that, despite moments of pure exasperation, Julien is the love of Austin’s life. Now, in the shadow of death, Julien will try, with Austin’s help, to live all he can, as Strether advises Little Bilham to do in The Ambassadors, as Peter, Austin’s friend, who is dying, says in Key West: “Oh Austin, I’m determined to live as much as I can.”

Thus the novel turns from being the story of a middle-aged man finding young love and trying to live up to it to the story of a young man, who knows he is doomed, setting out to find a protector who will look after him as he declines. Austin has been fooled. Once again, it is an aspect of Edmund White’s subtlety that he does not make this discovery into a long night of the soul for Austin. He makes it merely another layer in a story of many layers, many motives and nuances and moments of truth and untruth.

By making Austin Smith a stranger in France and then, even more, a stranger in America, Edmund White can isolate and then intensify Austin’s consciousness and his ways of noticing and thinking. Late in the book, Austin meets Rod, a fellow Europeanized American, at a reading in Paris and finds that they can laugh at the same jokes. Part of the drama of the love story at the core of the book is that although Austin and Julien are men and their sexuality makes them similar, their nationalities makes them totally different from each other. If Austin in this novel is a married man, then the marriage is to someone of the opposite nationality. They will never laugh at the same jokes.

In The Ambassadors, the recognition scene comes towards the end of book. Strether, still in search of sensation, travels out of Paris by train at random to sample the French countryside where, in an out-of-the-way place, he sees Chad and Madame de Vionnet and realizes the unmistakable relation between them. James manages to conjure up the scene in all its affecting and electrifying detail, as he did in a scene in The Portrait of a Lady when Isabel enters the room and finds Madame Merle standing close to the fire and Osmond, Isabel’s husband, seated. “Their relative positions, their absorbed mutual gaze, struck her as something detected.” So, too, in this scene in The Ambassadors, Strether’s ability finally to see clearly becomes a way for his innocence to be darkened.

In The Married Man Edmund White is not interested in following the emotional structure of The Ambassadors to the letter, or doing a modern version of it scene by scene. He uses its contours and textures when he needs them, but he has his own novel to write. The Married Man is not a literary exercise. White charts the slow decline of Julien with both sympathy and care so that the novel becomes a drama about Julien’s body itself and its defenses, or lack of them, rather than his moral sensibility, or indeed his soul. Julien is flawed in many ways, but these flaws serve to nourish the novel. Julien is also suffering from a cruel and slow disease and his bravery in the face of suffering, his will to live all he can, allow him to soar above mere moral questions, or at least evade them or exhaust them.

The other question then, the issue of his deceptions, is finally rendered almost as comedy. After Julien’s death, Austin discovers that his lover’s mother did not have a career as a concert pianist, but as an accordionist. “Austin realized that everything Julien had said about his family had been compounded of lies. His parents had not been aristocrats but a beautician and a shipping clerk, just as his maternal grandparents had been a railway man and a farm worker.” He learns too that Julien had had many male lovers before him and that his bisexuality was an alibi, a myth.

It is an aspect of the genius of the novel that neither the reader nor Austin judges Julien harshly now. It is not as though Edmund White has waited until the end of the book to give us all a lesson in morality and make us re-think the book in the clear light of the difference between truth and lies. Instead, he allows Austin to miss Julien; he writes tenderly about grief in all its strangeness, all its unexpectedness: “Austin felt that an enormous thing had happened to him, Julien’s death, and he wanted to share it with the most important person in his life: Julien. His frustration about Julien’s silence made him talk out loud to him.”

At the very end of the book, when all the facts have been made clear, Austin goes back to America, to Key West to see his friend Peter, who is now seriously ill, for the last time. In these scenes, Edmund White evokes, with tenderness too, moments of sweet loyalty and friendship and deep regret. He gives Austin Smith back his innocence, without undermining the sharpness of the experience he has lived through with his French lover in the pages of The Married Man.