Nicole Sealey: On Being Inspired by the NYC Ball Scene and Writing With Empathy

Author: Christopher Soto

December 6, 2017

Nicole Sealey and I first met in 2013 when we were both studying poetry at New York University. For some reason we didn’t cross paths during the first semester of school and people kept on telling me “How is it possible that you and Nicole Sealey haven’t met yet?!” I actually remember poet Saeed Jones as the first person to pose this question to me (and he didn’t even attend our school).

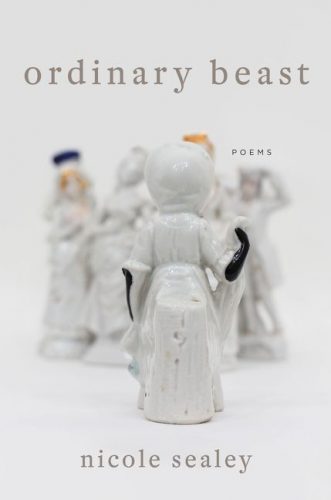

Since those years, where Nicole and I both meandered the halls of NYU, she has received fellowships from the Elizabeth George Foundation and CantoMundo, she has been published in the New Yorker, she has become the Executive Director of Cave Canem, and most notably her first full length collection of poetry, Ordinary Beast, was published this fall by Ecco. It is extremely rare to hear of a debut poetry collection coming off of one of the largest presses in America. This, amongst Nicole Sealey’s other accolades and work produced, is a testament to her talent and influence as a poet. Sealey was born in the Virgin Islands and raised in Florida. She currently resides in New York City, where she lives with her husband and fellow poet, John Murillo.

In this interview, Sealey generously took some time to talk with me about the queerness of her first book, the NYC ball scene, cultural appropriation, literary inspiration, and more.

You were known to be an extremely slow and precise writer in class.

Yes, I write slowly. Writing is an opportunity to say exactly what I mean. I’ve never read the E.M. Foster novel that Richard Hugo mentions in chapter one of The Triggering Town, but I completed agree with the character he quotes: “How do I know what I think until I see what I’ve said?”

When did you write the earliest poem in Ordinary Beast? How did the book come about?

I began drafting the earliest poem in Ordinary Beast in 2005 or 2006. I couldn’t tell you when I actually finished it though. (Is a poem ever finished?) Now, with the book in my hands, the memory of the process feels so otherworldly. So much so that I often think: “How did I do this.” The gods must’ve conspired in my favor? That’s really my best answer for how the book came about.

How did you come to poetry?

I came to poetry about seventeen years ago on the heels of a breakup. Those poems were ego-driven and, quite frankly, not any good. A handful of years later, I found myself participating in a Cave Canem 8-week workshop. Cave Canem, as you know, is an organization dedicated to cultivating the growth of black poets and the organization to which I owe a great debt. Literally, those free workshops at Cave Canem taught me how to write poems.

The second line of your book quickly queers the project. You write, “I’ve had sex with a man/who’s had sex with men.” Was this early queering an intentional foreshadowing?

The early queering, as you say, was unintentional—maybe subconsciously intentional. I knew I wanted to open Ordinary Beast with a poem that would allow me to say who I am, what I believe and who I love up front. “Medical History,” I think, does this, addressing what the reader can expect both aesthetically and politically. Aesthetically, lyric-narrative (heavy on the lyric). Politically, pro-love.

By the fifth poem in the book, “Legendary,” Venus Xtravaganza appears. What is your relationship to the ball scene?

By the fifth poem in the book, “Legendary,” Venus Xtravaganza appears. What is your relationship to the ball scene?

Oh, yes, Venus Extravaganza. (As a Latinx trans woman, Xtravaganza understood the kind of currency whiteness carries and earnestly wished to be a “spoiled rich white girl.”)

I’ve attended balls as an admirer—an art enthusiast and lover of all things beautiful. A friend of fifteen years actually promotes and sponsors balls across the country. His love of and enthusiasm for the art inspired mine. Plus, believe it or not, I was my high school’s homecoming queen, so the pomp and circumstance of it all felt/feels very natural to me.

I’m thinking about how often culture created by black women is appropriated by white gay men. I’m wondering what it means for a cis-hetereo black woman to use the language and culture of the ball scene. Do you believe there is a difference between appropriation, embodiment, and homage?

The “Legendary” poems, of which there are three in Ordinary Beast, are my limited and loose impressions of Venus Xtravaganza, Pepper LaBeija and Octavia Saint Laurent. I’m not attempting to speak for them. It’s not my place to do so, nor would I want to.

The obvious differences between the white gay males about whom you speak and me are power and privilege. As a black woman, I have my own oppression from which to draw. And, I make a conscious effort to write from a point of empathy and inclusion. There’s a big difference between appropriation, embodiment and homage. Appropriation is colonization. Embodiment, depending on treatment, is exoticization. Homage is exaltation. Empathy, I think, allows for exaltation.

You’re generous with your credits to figures in the ball scene and the relationship feels genuine. How did you conduct research for the series? How did you decide whom to honor?

Without the genius of Xtravaganza, LaBeija and Saint Laurent there would be no “Legendary.” I kid you not, I must’ve watched Paris Is Burning (in part or entirely) at least 200 times. I attended balls, watched hours of pageants, researched performers, sat with the work, and became best friends with Webster’s Rhyming Dictionary.

A decade ago, I had it in my mind to write a poem to honor each person featured in Paris Is Burning… It hasn’t quite worked out that way. I have failed poems not in Ordinary Beast, for example, inspired by Dorian Corey, Willie Ninja and Freddie Pendavis. I haven’t yet found the words for these poems (or the words haven’t yet found me?). The Ordinary Beast galley includes the Dorian Corey poem, but I actually pulled it at the 25th hour because it didn’t feel finished.

As you likely know, Paris is Burning, has had some controversy around the film. Many queer activists of color have said that the white film director exploited the New York Ball scene for the film. What are your thoughts about using this film as a reference point?

From what I’ve read, those featured got very little for their time and talent. Since its release, Paris Is Burning has received more than a dozen awards and honors. It has made more than 3.5 million dollars and can now be streamed on Netflix. The producers, however, have paid approximately $55,000 to thirteen people featured in the film, which is about $4,200 each. This is the very definition of exploitation. Folks signed releases, so the producers’ actions, I believe, are within the law but without morals.

The filmmakers have exploited and continue to exploit a group of people who were generous enough to allow them access. I credit the film because ethically I must, but all praise to the people whose art is the actual inspiration for these poems.

How do the “Legendary” poems interact with each other? Do the epigraphs inspire the content, or does the content inspire the epigraph selections?

These poems are in conversation. Seeing that they’re coming from the same place of awe and honor, how could they not be in dialogue?

The epigraphs inspired and drove the content. Without the epigraphs, I’d be lost, especially considering these poems are Shakespearean sonnets and, therefore, bound by form. The epigraphs (and the form) provided direction, without which these poems would have no end.

If you could be in any house, which house would you be in? Why?

I know better than to answer this question. (That’ like asking me which sorority would I have pledged.)

I’m thinking about the phrase “drag queen” and how it was sometimes used to reference trans women. How do you treat queer jargon of the past in relationship to definitions and distinctions of today? How do you code-switch (and time-switch) amongst the communities in Ordinary Beast?

It becomes easy to code switch when code-switching is part of your everyday life. The one word I use specific to the ball scene is “fem-realness,” and I believe the term was used back in the day and is still used today. Because this world is not my own, I am careful not to behave overly familiar—I want to always err on the side of sensitivity and respect.

I know the difference between in-group and out-group language. I don’t want to be that person who not only over stays her welcome but also comes to believe the house is half hers. It isn’t. As an ally, I know my place.

In the poem “Virginia is for Lovers” you note “LaToya’s Pride picnic.” The word “pride” changes the atmosphere of the poem. How did you decide on this inclusion? Do you consider this work part of a queer literary tradition?

“Virginia is for Lovers” was literally inspired by an incident that happened at a friend’s annual Pride picnic. Not that poems ought to always tell the truth but, in this instance, the truth better served the poem. I couldn’t see the scene anywhere except at the “Pride picnic,” which situates the poem in a place as well as a politic.

I identify as an ally, so I don’t consider this work part of a queer literary tradition. I could see, however, how one might consider it in the tradition of witness.

Before we end, a quick question about craft. Do you often write in closed form? It’s rare (and impressive) to come by these days.

I’ve found that poems sometimes demand received forms. About half of Ordinary Beast is written in a form other than free verse—even the poems that appear informal have formal elements. Form is a poetic tool just as metaphor and enjambment are poetic tools. I’m just trying to use all the tools in my toolbox.