Matthew Gallaway: On His New Novel and Finding a Different Kind of Faith

Author: Philip F. Clark

October 19, 2017

Matthew Gallaway’s debut novel The Metropolis Case, published in 2010, is an ambitious novel based on Janacek’s opera, The Makropulos Case,—filled with mysterious and haunting ideas of eternal life, mythic characters, and a page-turning plot.

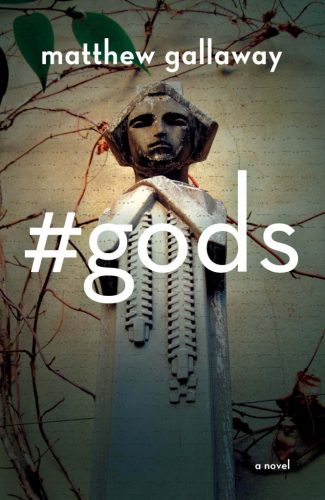

In his newest book, #gods, published in August, Gallaway once again mesmerizes readers with memorable protagonists, New York noir, haunted men, classical myths, and an unswerving eroticism.

From the publisher:

A young boy wanders into the woods of Harlem and witnesses the abduction of his sister by a glowing creature. Forty years later, now working as a New York City homicide detective, Gus is assigned to a case in which he unexpectedly succumbs to a vision that Helen is still alive. To find her, he embarks on an unorthodox investigation that leads to an ancient civilization of gods and the people determined to bring them back.

Lambda Literary recently interviewed Gallaway about the development of his new novel, the realities of the publishing world for gay writers, and sexuality as affirmation.

#gods has many portals to enter as a reader: a romance, a mystery, a memoir, a ghost story–it’s a novel of the tangible world, yet it sets that world on its head, asking the reader to consider themes of faith, belief, and disbelief. How did #gods come to be?

As I’ve gotten older and more introspective, I’ve become interested in individual expressions of protest. One area I find particularly intriguing in this regard is how people think about “faith” outside of traditional, mainstream religious institutions, which I don’t think have any real authority on the issue, despite a very long history of (mostly insane, self-serving, and discriminatory) rule-making and posturing. My sense is that a lot of us believe in “something” but don’t spend too much time putting parameters around exactly what it is. But when we do, there’s often a subversive quality to our beliefs that I think can be very empowering—in personal and political senses—and, for me, writing #gods was an attempt to define my faith in a very specific, subjective (and empowering) way.

More specifically, my definition of faith turned out to be less about an omnipotent, judgmental God or the threat/promise of an afterlife and more about things like music, mythology, my favorite television shows, tween rebellion, and (gay) sex; in short, all of the things I value, not only because they make me feel alive, but also because of how they serve to connect me to something “bigger” and—possibly—“divine” (but without making me feel “small” or insignificant, which I think is an important paradox of faith: it’s a source of power and humility).

It turned out that the best way to capture this idea was to write a novel that—like the faith I was trying to describe—incorporates many different styles, voices, and genres. There are many Big Novels that I love or at least admire—Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace and 2666 by Roberto Bolaño are two relatively recent examples—but I sometimes get the impression that Big Publishing, at least in its current form, tends to limit these works to straight, white writers (usually men). Women and gay men are expected to be more “traditional” in form and style, while straight men—who generally speaking are incapacitated by emotion (and mock it)—are revered for bending and mixing genres; they build these massive structures that are impressive to behold but are often very cold on the inside. As a gay man, I wanted to subvert this convention by writing something that’s structurally complex and also beautiful and emotional.

Gay literature seems to pre-suppose a fulcrum on sex and desire. But those events in your novel are made more indelible—certainly, in one example, the sex between the character Cecil, when he was a teenager, and his hockey coach. While this relationship can be read as ephebophilia (and its context shows that on the coach’s part it is), you also permit Cecil to show power by resisting feeling shame. How did you decide to handle this subject in that way?

With Cecil and his hockey coach, I wanted to take a “narrative” that we’ve all read about countless times—the older man/priest/coach “molesting” or “abusing” his “victim”—and deconstruct it; not as an endorsement of the relationship (which, for the record, I think is prima facie immoral), but in a manner that (in this case) dispels the notion of victimhood. There’s no “shame” or “embarrassment” for Cecil. If anything, by recognizing what’s happened to him and understanding why it’s wrong—on human and societal levels (because our collective homophobia enables these relationships)—Cecil is “radicalized” and empowered. It’s what prompts him to leave straight society and devote his life to being gay in ways that are, again, both personal and political

You have incorporated desire in the novel without a surfeit of mechanics and acrobatics in sexual description, but rather you explore the real emotion behind the acts. Can you speak to this?

Writing sex scenes is never easy, and I think there’s an understandable tendency among gay writers to be a little “in your face” about what’s happening, mostly because we so rarely get to see gay characters (much less gay sex) in the mainstream books/movies/television shows that everyone talks about 24/7. In writing this book, I tried to recognize this impulse but transcend it, because I wanted the descriptions of gay sex to be about more than just reactionary anger; I wanted the sex to be “awesome” (in every sense) in terms of physical pleasure (most obviously) and intimacy, while conveying a kind of emotional vulnerability (implicit in physical penetration, when you’re the one being penetrated) that I think is foreign to many straight men and (sadly/hilariously) terrifies them (which is why it becomes a source of political power for those of us engaging in the act). I tried to be graphic enough so that there’s zero doubt about what’s happening, but not so “clinical” or detailed that the writing becomes “over the top” or overwrought (or angry).

One example of this kind of balancing act, which I found very helpful, is House Rules, an amazing 1994 novel by Heather Lewis in which she describes a series of (woman/woman) sex scenes that had me sweating in a good way (when I least expected this to happen). I studied that book a lot and tried to capture its energy. I also found this blog post by Rich Juzwiak at Gawker (R.I.P.) to be influential on my thinking to the extent that—as sometimes happens while writing a novel—it summed up in a few words something that I was trying to convey through the (sexual) actions of several characters in #gods, namely the idea that (in Juzwiak’s words) “[b]elief in the implicit supremacy of man-on-man sex is the closest thing I have to faith.”

The novel is also strong because–as a queer manifesto in a sense–its characters live with a purpose of being and living their lives as gay men and women, and that is evident from the first. For Cecil, it is a revelation, coming from his experience. It becomes his “living out” rather than his “coming out.“

The novel is also strong because–as a queer manifesto in a sense–its characters live with a purpose of being and living their lives as gay men and women, and that is evident from the first. For Cecil, it is a revelation, coming from his experience. It becomes his “living out” rather than his “coming out.“

Cecil is an exaggerated character, someone who represents idealism with very little compromise. He’s given an opportunity I think many of us fantasize about, particularly when we’re teenagers, to literally kill himself (as far as the rest of the world is concerned) before being reinvented as a kind of gay “secret agent,” sort of my version of a hot gay bear/post-Marxist James Bond who’s working to fight the worst impulses of our government and the corporations it primarily serves. He 100-percent lives his truth, which I hope makes him very attractive.

Your novel contains a wealth of diverse charters, from communities you are not necessarily a part of. There has been a lot of discussion in the press about cultural appropriation in literature; did these discussions come into play as you crafted this novel?

As a long-term resident of a neighborhood where the majority of people are not white, I felt it was important, if I wanted to set the book in Harlem/Washington Heights, to represent that reality. By the same token, I don’t want to pretend that I—as a white man—have the same authority as someone who’s not white, which is why I also included some explicit “meta” discussion about what it means for someone who’s not part of a minority group to write from that vantage point. I strongly believe that writers should feel free to take these kinds of risks and appropriate from wherever they find inspiration, but in doing so should ideally display some sensitivity to the real world. In gay literature, there are (in my view) a frankly alarming number of highly acclaimed books about gay men written by people who are not gay men; while some are more “believable” than others (and many I find exploitative), these books can at least promote a discussion about what it means to live in someone else’s shoes, which is an element of empathy or compassion that’s greatly lacking in our political system on both sides of the aisle, and where I think literature can help.

I want to speak to the design and structure of the book. The chapters have significant–and arresting–headings, which call to the mythic and human qualities many times in the book: “Les Chimeres,“ “The Gate of Proitides,“ “The Gate of Homoloides (Love),“ “A Children’s Guide On How To Conduct A Struggle,“–these immediately prepare the reader for something to come. You also break the usual linear, textual design of chapters–one chapter is a whole bullet list. What inspired some of your decisions in playing with the text?

Being a big proponent of artistic appropriation or (less euphemistically)—theft—I wanted to leave clues throughout the text about where I was drawing inspiration (or stealing), whether it was from Plato, Pythagoras of Samos, Rainer Maria Rilke, Gustave Moreau, Don DeLillo, Emily Bronte, June Jordan, and many more, along with the operas and rock bands and television shows whose dialog I quote (Buffy, Twin Peaks, Battlestar Galactica, Empire, etc.). I don’t believe in distinctions between “high” and “low” art, and my hope is that the book reflects this philosophy, in keeping with the idea that each of us finds many sources to create our individual faiths.

The novel is also an exercise in New York City noir; the city is the dark and sometimes subterranean world. What is it about New York that fascinates you the most as a setting for your works?

I think New York City, and particularly uptown (by which I mean north of 110th Street), exemplifies extremes of brilliance and degradation in our society. Navigating these extremes—which often means appearing and disappearing—is something that I hope comes across in the book and its settings, along with the characters—and, ultimately, the readers—who are doing the same. Gay people have historically gravitated to the “margins” of conventional society, and New York City, even now, is filled with spaces that are considered decrepit or unsafe by a lot of “respectable” people but are considered home—with all of the pleasure and comfort that implies—to many outsiders.