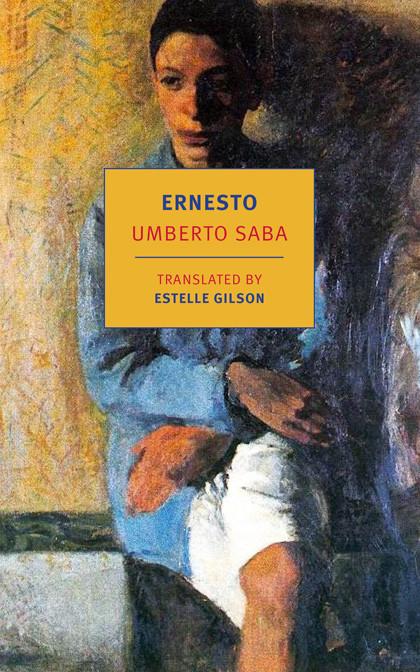

‘Ernesto’ by Umberto Saba

Author: Steven Cordova

October 10, 2017

Ernesto is a “lost novel” found. The Italian poet Umberto Saba wrote the story in 1953. He was convalescing in a mental institution at the time, and there he recorded that the autobiographical bildungsroman—a novella, really—“poured out” of him. “It was as if a dike had broken in me, and everything poured out all at once.” The decidedly queer nature of the story nevertheless rendered the novella difficult to publish at the time. Saba’s daughter kept the manuscript hidden until 1975, at which time it was published in Italian.

This year the ever-more gay friendly press New York Review Books has published an English-language translation. Estelle Gilson, Ernesto’s godsent-translator, introduces the text, and estimates that “Ernesto has become a landmark in Italian and international homosexual literature.” Beyond that achievement, Gilson concludes, “Ernesto’s nuanced voicing adds layers of intensity to this classic story. In a tightly compressed style animated with flashes of poetic insight, Saba’s prose achieves the directness, clarity, and honesty that characterized his poetry.”

The coming-of-age arc of Ernesto’s story will be familiar to many queer readers; the setting somewhat less so. Saba’s eponymous hero is a precocious 16-year-old living in Trieste, Italy in 1898. (Trieste’s dialect is now extinct.) Ernesto fancies himself a Socialist, and has dreams of being a concert violinist. “Deep in his heart, however, he had barely any hope for it. He wasn’t that crazy; he knew from the relatively late age at which he began studying the instrument, it would be hard going ….” Ernesto, as you may have already gleaned, is also unusually clear-minded and straight forward. “Youngsters generally try to pass themselves off as sophisticated rather than inexperienced. And the harder they pretend to be the former, the more likely they are to be the latter. But that was not Ernesto’s way.”

One day, a laborer—a character known for the rest of the novella only as “the man”—propositions him.

“Don’t you know what you’d like to do with you?” [the man asked].

“Yeah, put it up my ass,” Ernesto replied with quiet innocence.

Ernesto acquiesces to the man and a short series of trysts between the two ensues.

The true tragedy here is that his mother has removed him from school in order to apprentice him with a flour import company where he meets “the man.” She is a misguided parent to boot. “One of her axioms was there’s no such thing as showing too much displeasure to a child.” She’s not, however, a two-dimensional evil character. She is financially indebted to a well-off sibling, and the sum effect of her debt is that “A school where her son is enjoying himself was decidedly not what she had in mind for Ernesto. Perhaps too she needed not too feel so completely dependent on her sister.”

Queer readers will also recognize the sudden turn to heterosexuality in the hero and the narrative; some may even read it as cowardice on Saba’s part. I don’t believe it is, or that Ernesto becomes invalidated as a “positive” queer text. “The unlikely reader of this tale,” as Saba himself points out, “is asked to recall that it is taking place in 1898, in Trieste.” And though the relationship between Ernesto and the man ends, it doesn’t end in tragedy. No one kills themselves here. Nor is the central relationship of the novella presented in a negative light. Love is possible in Saba’s queer world. Ernesto is “sure” that the laborer “had (in his own way) loved him. And perhaps (if Ernesto wanted him to) would go on loving him.” The man, for his own part, is sure that “In addition to the love he felt for the boy (rare in a man of his disposition), with Ernesto he hadn’t experienced any of the revulsion that overcame him with other boys, from whom he would distance himself—flee—as soon as he’d had them.”

The only character who is presented in a negative light is Ernesto’s overbearing uncle, who often sups with Ernesto and his mother. A conservative, he has given up talking to the Socialist Ernesto about politics. “However, one day, using the example of a citywide scandal about a well-known public person—who seemed to have the same predilections as the man —his uncle pointed a finger at Ernesto, and staring directly into his eyes said, ‘When a man has done such things, if he is a man, there is nothing for him to do but shoot himself.’” Ernesto doesn’t believes his uncle suspects anything about his trysts, nevertheless “his uncle’s words …remained stamped in the boy’s mind and were, perhaps, the final cause for the inevitable but sudden break with the man. He was more and more afraid of his uncle.”

Any easy dismissal of Ernesto would also miss out on the poetic insight, as well as on the novella’s considerable humor. After the first tryst between the man and Ernesto, for instance, we get this wry scene:

“Was it good for you?” Ernesto asked.

“I was in paradise. But you liked it, too, say so.”

“Not that much! A little at the beginning, then it began to hurt. I even shouted.”

“You shouted?”

“Did you hear me when I said ‘Ow’? And why did you call me angel?”

“What else should I call you?”

“Angels don’t do that kind of thing,” Ernesto replied sternly.

In addition to the introduction by Gilson, she also provides a supplementary “On Translating Ernesto,” and Maria Antonietta Grigani provides “The History of Saba’s Ernesto.” These, along with the draft of a provisional chapter of the novel and a letter Saba wrote to an acquaintance in the voice of the character Ernesto, give this important publication its much-deserved due.

Ernesto

By Umberto Saba

New York Review of Books

Paperback, 9781681370828, 160 pp.

March 2017