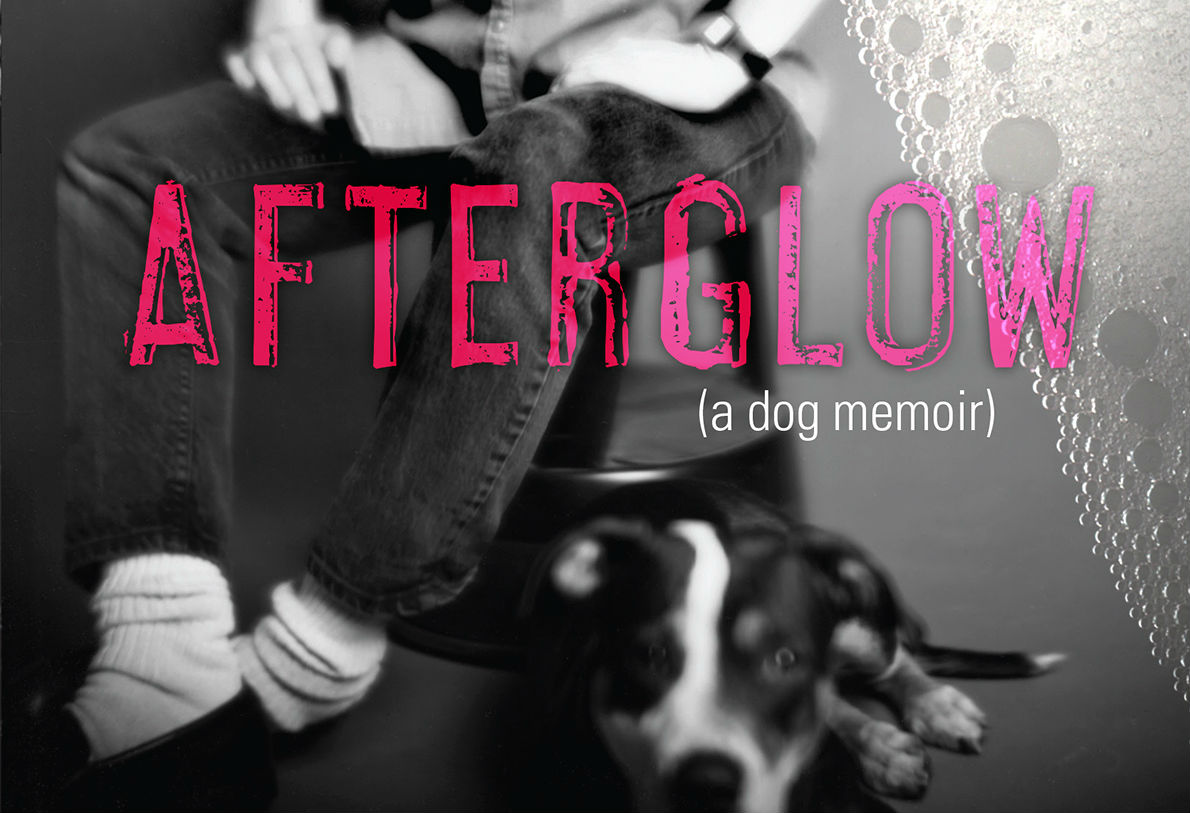

‘Afterglow (A Dog Memoir)’ by Eileen Myles

Author: Liz von Klemperer

September 11, 2017

I’m not a dog lover, but I am a longtime Eileen Myles fan, so I eagerly delved into the author’s memoir Afterglow, which pays homage to Myles’ now deceased pit-bull, Rosie. I trusted Myles to take me on an engaging journey, and perhaps even change my tepid feelings about man’s best friend. Myles did both of those things, as well as redefined my concept of what a memoir can be, as Afterglow is a multi genre tapestry seen through the perspective of both human and dog.

Afterglow is perhaps Myles’ most experimental work to date. Although broadly categorized as a memoir, it takes the form of disjointed poetic prose, doodles, iPhone photography, transcriptions of audio and video recordings, and much more. Although Myles’ anguish over the loss of Rosie is at the center of the book, all the heartbreak is tempered with comic absurdity. In the chapter “The Dog’s Journey,” for example, Rosie speaks from the afterlife to counsel Myles about the author’s writing. The book is thus transformed into a collaborative effort as opposed to an ode. Rosie lectures Myles, and Myles offers monosyllabic responses such as “wow” and “sure,” comically reversing the roles of master and pet. Rosie often chides Myles condescendingly while Myles stumbles to follow Rosie’s teachings. It is clear from the beginning that Rosie is not merely Myles’ pet, but a spiritual guide and an example to uphold. Rosie is a “Little god!” as Myles is able to perceive reality untainted by the egos and preconceptions that plague humans.

Rosie’s sage status is expressed through Myles’ transcription of a video rerecorded while walking Rosie through a park. This segment is lyrical in form and poetic in content, as the perspective moves abruptly from image to image. Myles offers no analysis of the experience, instead hyper-focusing on fleeting details, such as light reflecting through tree branches or Rosie eating a piece of chicken found in the bushes. This is Myles’ attempt to capture the pure physicality of Rosie on paper, an ultimately paradoxical task that Myles is playfully aware of. To Myles, human perception is limiting and inaccurate. It is difficult for humans to live outside their physical reality, as:

The little living human is framed, continually, by opposites. One of the ways we experience this is in the living realm is in the limitations of things. Can we accept this longing, feel it, even maybe occasionally go down to the beach. Jump in, dry off and walk on. Do we accept our fate?

Human suffering is caused by desire and the obsession with wish fulfillment. Rosie, on the other hand, was able to exist without suffering despite the fact that she was dying. Myles describes Rosie at age 15, a year before she died, as having:

A soft torso that used to be strong but the width and the heroic bone structure, ripples and inclines now say where the muscles were. She doesn’t care. She wears her body like her favorite clothing. Age is a slight inconvenience on her way to sudden meals.

Although Myles does not directly reference Eastern Philosophy, the concept of the dog mind echoes Buddhist teachings of peace with impermanence and suffering. Myles uses unique terminology, and describes the act of witnessing reality without judgment as “choose listening.” To survive, “one must look straight into the face of the nun or whoever and muse…warily I learned not to absorb their enmity.” Myles is trying to “duplicate what the dog sees” through writing but it isn’t easy, as writing is ultimately an act of reflection and therefore a distancing from unmediated physical experience. The attempt to translate the written word into a type of meditation, however, is mesmerizing. Myles defies conventional narrative in the pursuit of enlightenment: the pure and heightened perception of the dog.

The dichotomy of the grounded dog mind and the cerebral human mind mirrors Myles’own writing practice. In Myles’ best moments, a stirring refection occurs, the author stating, “[…] written myself away somehow. Yet this is what writing is. A leaving behind.”

At the same time, Myles says, “I have a wind in my heart and I admit it is often eased not just by the act of writing, but money. Yeah. That too. Cause there is also the experience of being seen as a writer, getting chosen, thereby that way getting money.” Here the desire to abandon ego is at odds with desire rooted in societal recognition. Myles wants the reader to know that there is no easy end to this quest, but that they will doggedly (excuse the pun) keep trying.

Despite various forms of self-deprecation, the author has glimpses into the world of dog-like perception. One example is Myles’ experience in a support group, where Myles becomes preoccupied with formulating an interesting response to someone’s comment. Myles is aware that this particular desire is disingenuous and self-serving, but is bent on following through. Myles suddenly notices that Rosie, who is still a puppy, is roaming around the room and may have shat on the floor. Instead of delivering an eloquent response Myles panics and says to the group, “that’s my puppy Rosie walking around and…I was just wondering if she already had shit on the floor.” The room breaks out in laughter. This is the type of genuine and spontaneous expression the author craves, and what Myles’ wants to embody in their writing. Myles’ wants dog shit over metaphor and inquiry.

Myles attempts one last time to translate the ego-less dog mind into text in “The Walk.” “The Walk” is a bare bones, transcribed recording of Myles’ walk through the woods to scatter Rosie’s ashes. Myles’ brings a close friend and the conversation is clipped and mundane. Sentences taper off, and half jokes abound. The ultimate scattering of the ashes is wrenching in its sparseness. When the ashes stick to a rock, Myles swirls the water to dislodge them, saying, simply, “Ok baby. Rosie girl,” and then, finally, “bye baby girl.” Myles ultimately succeeds in honoring Rosie’s life not through sentimental reflections or expositions of grief, but by embodying the wisdom of the dog: to breathe in every smell on the street, and to be here, now.

Afterglow (A Dog Memoir)

By Eileen Myles

Grove Press

Hardcover, 9780802127099, 224 pp.

September 2017