Notes for a Prospective Biographer: Remembrances on Gwendolyn Brooks’ Hundredth Birthday

Author: Evelyn White

June 19, 2017

“I believe that we should all know each other, we human carriers of so many pleasurable differences. To not know is to doubt, to shrink from, sidestep or destroy.”

Penned in a sprawling script that registered despair rather than grandiosity, the close of the letter read: “I’ll understand if you decide to drop the whole thing.”

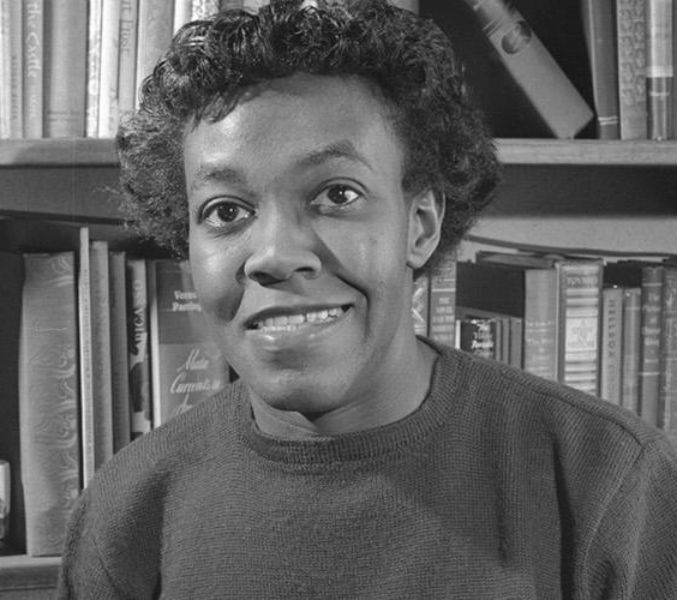

Dated February 1, 2000, the dispatch had been mailed to me by the poet Gwendolyn Brooks. June 7th marked the one-hundredth birthday of the first black person to win a Pulitzer Prize in any genre.

Brooks claimed the prestigious award for her poetry collection Annie Allen (1949), which chronicles a black girl’s growth into womanhood. “The Anniad,” the volume’s highly-praised middle section, (a play on Homer’s Iliad) begins:

Think of sweet and chocolate

Left to folly or to fate

Whom the higher gods forgot

Whom the lower gods berate

In their landmark decision, the Pulitzer Prize poetry judges declared the volume’s release “truly objective, never propagandistic, and above all original.”

Brooks would showcase similar talents in Children Coming Home (1991), an undervalued collection that she rendered from the perspective of youths. In “Religion,” a boy named Ulysses introduces readers to his unconventional family. The poem exmplifies the growing need for an examination of Brooks’ work through an LGBTQ lens.

At home we pray every morning…

and we sing Hallelujah…

Daddy speeds, to break bread with his Girl Friend

Mommy’s a Boss. And a lesbian

(She too has a nice Girlfriend.)

Brooks’ letter to me had been prompted by a request to reprint an excerpt from her poem, “To Black Women,” in my book, Alice Walker: A Life (2004). Displeased with the lines I’d selected, Brooks replied:

I’ll allow you to reprint—for not one dime—PROVIDED you respect this letter’s requirement.… The poem must be published as written, or not at all. No revisions, no excerpting, no adjustments.… I try so hard. I spend a lot of time toiling over my language: every dot and dash, every comma, every piece of alliteration, every italic MEANS something.…

By turns amused and disquieted by Brooks’ letter, I immediately agreed, in writing, to the terms she’d outlined.

*

As it happened, I’d previously interviewed Brooks about Alice Walker. Walker was the first black woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in fiction, for her 1982 novel, The Color Purple. During our chat at the University of California at Berkeley in April 1997, Brooks praised Walker, noting the tender sexual relationship between the female protagonists of her novel, Celie and Shug. “Alice is an adventurer,” Brooks said, admiringly.

Later that day, I attended a reading Brooks gave before a packed house at Berkeley. Throughout her life, Brooks exuded a prim reserve that belied a biting edge. Taking her place at the podium, the poet trained her eyes on the crowd with a steely gaze that said, “Don’t let the staid suit, tam-o-shanter and sensible shoes fool you. I can hang.”

She then let loose with “Ballad of Pearl May Lee.” Included in her debut release, A Street in Bronzeville (1945), the poem centers on the sexual liaison between a white woman and a black man. An excerpt reads:

You paid for your dinner, Sammy boy

And you didn’t pay with money.

You paid with your hide and my heart, Sammy boy

For your taste of pink and white honey…

The piece evoked gospel shouts from a spirited group of black women in the audience. Brooks—who’d also probed the slights suffered by (especially) dark-skinned black women in her semi-autobiographical novel, Maud Martha (1953)—acknowledged the response with a sly grin.

Bedazzled by the poet’s performance, I walked halfway home before I remembered that I’d driven to the event and had to backtrack to find my car.

*

Brooks died on December 3, 2000, at the age of 83, before “To Black Women” appeared in my Walker biography. I was honored to offer reflections on the author during a 2014 lecture at the University of Arizona.

In addition to my personal experiences, I discussed Brooks’ poem, “The Mother,” and its powerful opening: Abortions will not let you forget / You remember the children you got that you did not get. Published nearly three decades before the U.S. Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion, the piece (also found in Bronzeville), remains a provocative commentary on reproductive rights.

I also highlighted Brooks’ attendance at a 1967 conference of black writers at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The poet had just completed a reading tour at a predominately white college when, en-route home to Chicago, she decided to visit the historically black school.

Nearly fifty and a pillar of the literary elite, Brooks was gobsmacked by the work of dashiki-clad authors such as LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) at the gathering where cries of “death to whitey” prevailed.

“First, I was aware of a general energy, an electricity, in look, walk, speech, gesture of the young blackness all about me,” Brooks wrote in her autobiography, Report from Part One (1972). “ I had been ‘loved’ [at the white campus]. Here I was coldly respected.… An almost hysterical Gwendolyn B. walked about in amazement, listening, looking, learning.”

Brooks further noted in Report that her sojourn at Fisk prompted a shift in her artistry: “My aim, in my next future, is to write poems that…‘call’…black people in taverns, black people in alleys, black people in gutters…the consulate…on thrones.”

*

In solidarity with black liberation efforts, Brooks left her mainstream publisher, Harper & Row. After 1969, she published new work exclusively with black-owned ventures. She also self-published several titles.

The unorthodox move greatly diminished Brooks’ critical and commercial clout. As for smaller royalty checks and the loss of prestige affiliated with a major publisher, the Pulitzer Prize winner later said: “I felt I should not stay safely in the harbor.”

Brooks’ poem, “Paul Robeson,” featured in Family Pictures (1970), reflected her re-energized black focus:

…we are each other’s harvest

We are each other’s business

We are each other’s magnitude and bond.

*

After my lecture at the University of Arizona, I chatted with Monica Casper, a dean and professor of gender and women’s studies. In a surprising revelation, the Chicago native told me about her ties to Brooks’ husband, Henry Lowington Blakely II. “He played a big part in my youth,” she said.

An aspiring black writer, Blakely met Brooks at a 1937 political meeting in Chicago. The future author of nearly thirty books reportedly announced to her friends, “There is the man I’m going to marry.” They were both in their early twenties.

The couple wed two years later and had two children. Like Brooks, Blakely had a passion for poetry. But unlike his wife, who was first published at age thirteen and mentored by a guardedly gay Langston Hughes, Blakely’s literary ambitions became a “dream deferred.”

He instead worked various jobs, including driver for a soft-drink company and insurance adjuster.

Casper said that she was nine-years-old and with her mother, Pat Struck, when she first met Blakely at the home of Struck’s devoted friend, Louise Ambuel. Like Casper and her mom, Ambuel was white.

“It was the mid-1970s and Louise lived largely among black neighbors,” said Casper, now fifty. “We spent time at her house on numerous occasions. Henry lived with her and had a room that functioned as his office.”

A native of Montana, Theresa Louise Ambuel had taught biology at Chicago’s Woodrow Wilson Junior College (now Kennedy-King College), since 1961.

“As I got older, I realized that Henry was married to Gwendolyn Brooks,” Casper continued. “I had questions for my mother but just accepted, even as young adults do, what we are exposed to as children. In my eyes, Henry was Louise’s partner. The details were irrelevant.”

Struck had met Ambuel at a local church where the lively academic held leadership positions. “I was a young mother going through a rough patch in my first marriage,” said Struck, who also attended the Chicago parish. “Louise was a ‘doer.’ She knew I was struggling and took me under her wing.”

“Louise brought Henry to church,” Struck continued. “I don’t know how they met but they were clearly sweethearts. He was a very kind, generous and cultured man.”

Struck said that Blakely and Ambuel were not subject to racial taunts or hostilities. At least, not in her social circles. “If anyone had a problem with their relationship, I never saw it,” she maintained. “And Henry’s marital situation was not our affair.”

“Henry and Louise are among the important figures that I look back on with gratitude,” Casper added. “People of warmth and love who helped to raise my sister and me.”

Neither Casper nor her mother ever met Gwendolyn Brooks. “I did have a sense that she was a very big deal,” Struck said, without a trace of irony.

Blakely died on July 3, 1996, at age 79. Struck joined the mourners at his memorial service.

And Ambuel? “Louise was deeply bereaved about Henry who was the only partner I ever knew her to have,” Struck said. “But she accepted that she had no right to attend the service.” Ambuel died at 93 years old, on September 27, 2014.

*

Interestingly, Gwendolyn Brooks had explored the challenges of marriage in a little-known essay, “Why Negro Women Leave Home.” Writing a dozen years before Betty Friedan lamented the domestic woes of suburban white women, in The Feminine Mystique (1963), Brooks put forth a (presumed) fictional spouse whose failings spur his wife to flee.

Published in Negro Digest (March 1951), Brooks writes: “He has a sad-eyed income and has been unfaithful to his wife…. Often there is sexual impotence or incompetence—or homosexuality—on the part of the man.… There is a growing number…who leave because the ‘other’ women are white.”

University of Maryland English professor Mary Helen Washington is a distinguished Brooks scholar. In a memorial tribute (Los Angeles Times, December 8, 2000), she noted that Brooks granted her permission to reprint the piece in an anthology and then “asked me to remove it.”

“She did not want the animosities between black men and women to be trumpeted before the white world,” Washington wrote. “I understood her reluctance, but also felt this was one area in which the intrepid interpreter of black life retreated.”

In A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks (2017), Angela Jackson chronicles an estrangement between the poet and her husband that began in 1969; a split that Brooks later described, varyingly, as a separation or a divorce.

“Old issues that had lain dormant in the marriage rose to the surface,” Jackson writes. “Gwendolyn was vague, suggesting simply that the marriage had run its course.”

A Surprised Queenhood is the first trade biography of the author since The Life of Gwendolyn Brooks (1990) by George E. Kent. Like Jackson, Kent also examined the poet’s domestic travails. But neither author presents Brooks as a black woman who found herself negotiating marital problems against the explosive backdrop of race.

On that front, it’s my view that both volumes fail scholars of African-American literature and everyday admirers of Gwendolyn Brooks, including queer readers.

*

It’s not difficult to imagine why Blakely’s romance with Ambuel would have rocked the poet’s world. Her racial identity fortified at Fisk, Brooks, by the 1970s, had emerged as a beloved griot of Black America. From her earliest work, the poet had decried the elevation of lightness over darkness. As a “cocoa straight” (her term) black woman, Brooks had skin in the game.

Jump cut to Ambuel and Blakely. “They were an ‘open secret,’” Pat Struck said. “I can’t imagine that Gwendolyn Brooks didn’t know.”

Taking a page from Emily Dickinson, the poet addressed the subject “slant,” in Report: “Black Woman…cannot endlessly brood on Black Man’s blondes, blues, blunders,” Brooks wrote. “She is a person in the world—with wrongs to right, stupidities to outwit, with her man when possible, on her own when not.”

I suspect that the secret strife in Brooks’ domestic life also fueled the pessimism in the letter I received: “I’ll understand if you decide to drop the whole thing.” This, from the first black person to win a Pulitzer Prize.

*

In The Way Forward Is With A Broken Heart (2000), Alice Walker writes candidly about the dissolution of her marriage to a white civil rights attorney. Sharing thoughts about Brooks via e-mail, she empathized with the poet: “I think she felt humiliated by…her husband.”

“There is a lesson for us here, if we are open to it,” Walker continued. “That we can bloom in our stoic beauty to create depthful and dignified spaces for others to stand. How we respond to this troubling revelation about a great poet’s life will reflect our own discomfort with healing medicine that may feel like it harms a famous legacy rather than extends it into a capacity to grow in understanding of our common struggle to be authentic, as well as free.”

In an interview with ABC News shortly before her death, Brooks put it this way: “I believe that we should all know each other, we human carriers of so many pleasurable differences. To not know is to doubt, to shrink from, sidestep or destroy.”

*

On the centennial year of the author’s birth, there’s material aplenty for a new Brooks biography in the tradition of other works about Pulitzer Prize-winning poets. Three volumes come immediately to mind: Holding On Upside Down: The Life and Work of Marianne Moore (2013) by Linda Leavell; Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay by Nancy Milford (2001); and Anne Sexton by Diane Wood Middlebrook (1991). Queer concerns (real and imagined) coursed through each poet’s life.

So let us consider anew Brooks’ only novel, Maud Martha. In addition to her cogent riffs on “color struck” blacks, the author also delivers a coded queer text that warrants further analysis. Throughout the narrative, Maud Martha’s husband, Paul, seeks (to no avail) membership in elite, social clubs where he can enjoy the company of men who sport “dapper handkerchiefs.”

“He was tired of his wife,” Brooks writes, noting Paul’s obsession with people who “knew what whiskies were good … how to dance…how to dress…and did not indulge (for the most part) in homosexuality but could discuss it without eagerness, distaste, curiosity—without anything but ennui.”

Two years after the release of Maud Martha, Brooks published a short story, “The Rise of Maud Martha” (1955). Crafted as the first chapter in a planned sequel to the novel, the saga presents the protagonist “mourning” Paul’s death in a fiery crash. He who had “so loved physical beauty,” had been transformed into a “repulsive thing” with nary a “dream of sophistication remaining,” Brooks writes. “[….] A road was again clean before her…all was up to her.”

*

And then there’s Brooks’ intriguing sonnet series, “Gay Chaps at the Bar.” Published in Bronzeville, the twelve interlocking poems center on soldiers during World War II—an era when the persecution of homosexuals in the armed forces was rampant. In “looking,” Brooks writes:

You have no word for soldiers to enjoy…

With masculine satisfaction…

Looking is better. At the dissolution

Grab greatly with the eye, crush in a steel

Of study

Later, the author offers “love note II: flags”:

Top, with a pretty glory and a merry

Softness, the scattered pound of my cold passion

I pull you down my foxhole. Do you mind?[…]

I let you flutter out against the pained

Volleys. Against my power crumpled and wan.

*

Now ponder “A Black Woman in Russia,” Brooks’ smack-down of lesbian literary icon Susan Sontag. Published in Report From Part Two (1996), the shade-filled piece recounts Brooks’ experience at a 1982 gathering of writers in the Soviet Union. Sontag was among those in the delegation.

The “determinedly intellectual” Sontag became enraged when a Russian journalist queried Brooks, the sole black person in the group, about African-American culture. “Susan is screaming,” Brooks writes. “My outrageous fancy that I know more about Being Black than she knows has pushed her to a wild-eyed frenzy.”

Brooks continues: “Finally (Sontag) utters an unforgettable sentence….‘I turn my back upon you.’ And she does.… She turns her back upon me, with a great shake of her bottom to appall me. I am ass-uredly impressed.”

*

This brings me to the body politic of today. Unlike multitudes of pollsters, Brooks envisioned (and warned against) a dramatic shift in American society that has come to pass. In a 1990 interview with critic D.H. Mehlem, the poet denounced forces that cast the U.S. as a nation diminished rather than strengthened by its diversity.

“Are (we) to renounce…all the richness that is our heritage,” Brooks said, concernedly. “Our new and final hero is to be Don John Trump.”

*

Note to prospective biographers: Your cup runneth over.