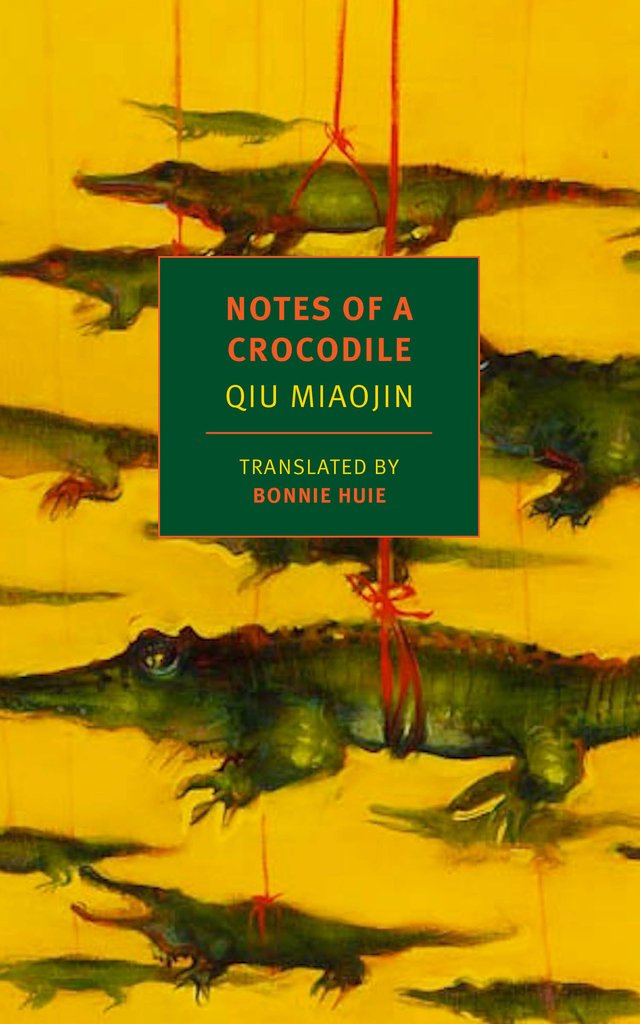

‘Notes of a Crocodile’ by Qiu Miaojin

Author: Liz von Klemperer

April 6, 2017

In a 2012 article in the Asian American Writers’ Workshop series The Margins, translator Bonnie Huie describes Qiu Miaojin’s style as containing “traces of real-life suffering that one can’t help reading into the work.” She’s right; it’s hard not to see Miaojin’s protagonist Lazi’s depressive and suicidal musings as ominous and foreboding, as the author committed suicide at the age of 26 soon after completing Notes on a Crocodile. In an article for Kyoto Journal, however, Huie writes that the novel is “intended to be a survival manual for teenagers, for a certain age when reading the right book can save your life.” It is in part this paradox that’s made Miaojin a counter-cultural icon, and her experimental work a cult classic in Taiwan. Her prose is in turns satirical, obsessive, and devastating, and explores “closetedness” amidst consuming romantic love, isolation, and crippling mental illness.

Notes of a Crocodile was written on the heels of China’s martial law rule in Taiwan. The novel is being reprinted in May by NYRB Classics, with a new translation from the Chinese by Bonnie Huie. The presence of queer literature in the 1990s was a direct result of this military exit, as Taiwan was opened to global trade and cultural cross-pollination. Newfound multiculturalism combined with the deregulation of free speech made for a more open and diverse landscape. Miaojin’s work addresses this newfound liberalism and comparatively fertile environment for queer Taiwanese writers, despite the fact that social stigma of LGBTQ+ people was still the norm.

Miaojin’s novel osculates between diary entries in which Lazi exhaustively recounts her romantic woes, and an absurdist reality in which crocodiles don human suits in order to assimilate. The diary entries are borderline excessive, and spare no detail about Lazi’s heartsickness. Her first love is Shui Ling, a woman she meets in her college English class. Although their courtship is brief, the agony Lazi experiences is abundant and often melodramatic. She gushes, comparing Shui Ling to “a rose beyond compare,” and describes her despair as “the weight of a gigantic mountain…crushing my skull.” Lazi acknowledges the tedium of her entries, saying:

I can drone on and on about my own love story, which takes place in the short distance between Wenzhou Street and Campus. Or I can throw in a few samples a la hip-hop or reggae. These readymades serve as an interlude to keep you from getting sick of the monotonous commute back and forth between these same two locations, again and again.

Her interludes about crocodiles serve as these “samples” to break up the monotony of singular place and idea.

Aside from agonizing about romantic interests, much of Lazi’s suffering is related to shame and denial of her own queerness, comparing her love of women to a “monstrous sin.” Lazi’s best friend Meng Sheng acts as an unbridled foil to her closetedness. Where as Lazi attempts to present more femme and date men, Meng Shen is open about his bisexuality and wears effeminate clothing. When he takes Lazi to a gay club and dances provocatively on stage, she is so uncomfortable she drinks excessively and vomits. Lazi’s says that her “femininity means having to hide [her] true feelings,” while Meng Sheng is aggressive in his intimacy. Their friendship begins when Lazi is in the midst of a depressive and self-isolating episode. Meng Sheng is so forward in his attempts to contact her that he hires a gang leader to send her a severed finger, along with a threatening message. If she doesn’t hang out with him, she’s next. Lazi finds this psychotic act endearing and honest, and the two become close.

Miaojin’s alternate crocodile world is both a satirical mirror of Lazi’s world as well as her fantasy. There is no gender in the land of the crocodile, and in lieu of pronouns crocodiles are referred to as “it.” In her journal, Lazi laments that, “all that is neither masculine nor feminine becomes sexless and is cast into the freezing-cold waters outside the line of demarcation.” Like Lazi, the crocodile also exits outside of society’s default construct. Like Lazi, the crocodile is inclined to conceal its true nature. While Lazi attempts fruitlessly to hide her depression and homosexuality, the crocodile wears a human suit over its scales. Amidst their seclusion they both long for companionship. Although “the crocodile had longed to meet its soul mate,” it cannot be sure that it’s ever met another crocodile, as its peers are similarly shrouded in human costumes. The very title of the book, Notes of a Crocodile, implies that Lazi’s journal entries are the musings of a crocodile.

The crocodile paradoxically is both celebrated and fetishized, as it is “thrust into the national spotlight and made a public figure,” but it is also treated as a dangerous and subversive entity. A televised debate between the Alliance for the Protection of Crocodiles and the Anti-Crocodile Coalition is a clear allusion to classic homophobic rhetoric. The Pro-Croc advocate says they should promote “crocodile eco tourism zones,” while the Anti-Croc spokesperson argues that crocodilism is contagious, and that the public is at risk. Both factions want to expose the crocodile and have an inflated image of what they know exists imperceptibly among them. In reality, however, the crocodile is thoroughly average and benign. It indulges in cream puffs, wipes its snout, watches TV, and knits. This satire reflects the simultaneous cultural presence and curiosity of queerness in Taiwan at the time, as well as the ingrained and predominant stigma.

A paper published by The International Institute for Asian Studies entitled “The Legacy of the Crocodile” affirms the lasting legacy of Notes of a Crocodile, stating that references to crocodiles and to the name Lazi were abundant in queer magazines and online subcultures throughout the mid-to-late 1990s. Thanks to Miaojin’s novel, those who were forced or compelled to pass as sexually or mentally normative were able to create a coded means through which congregate. Miaojin’s work has, in a way, fulfilled what both the narrator Lazi and the crocodile are yearning for throughout the book: communion and solace with like-minded creatures.

Notes of a Crocodile

By Qiu Miaojin (Translated by Bonnie Huie)

NYRB Classics

Paperback, 9781681370767, 256 pp.

May 2017