‘Wedlocked: The Perils of Marriage Equality’ by Katherine Franke

Author: Sarah Sarai

September 20, 2016

Marriage is a massive legal institution with more baggage than all the characters of Edith Wharton’s and Henry James’ novels combined have stowed on cruises to and from Europe. In Wedlocked: The Perils of Marriage Equality , Katherine Franke unpacks and investigates the “perils” by researching two groups which have not been shoo-ins for official acknowledgement—Black Americans, from newly freed slaves on; and queerfolk in this and the previous century.

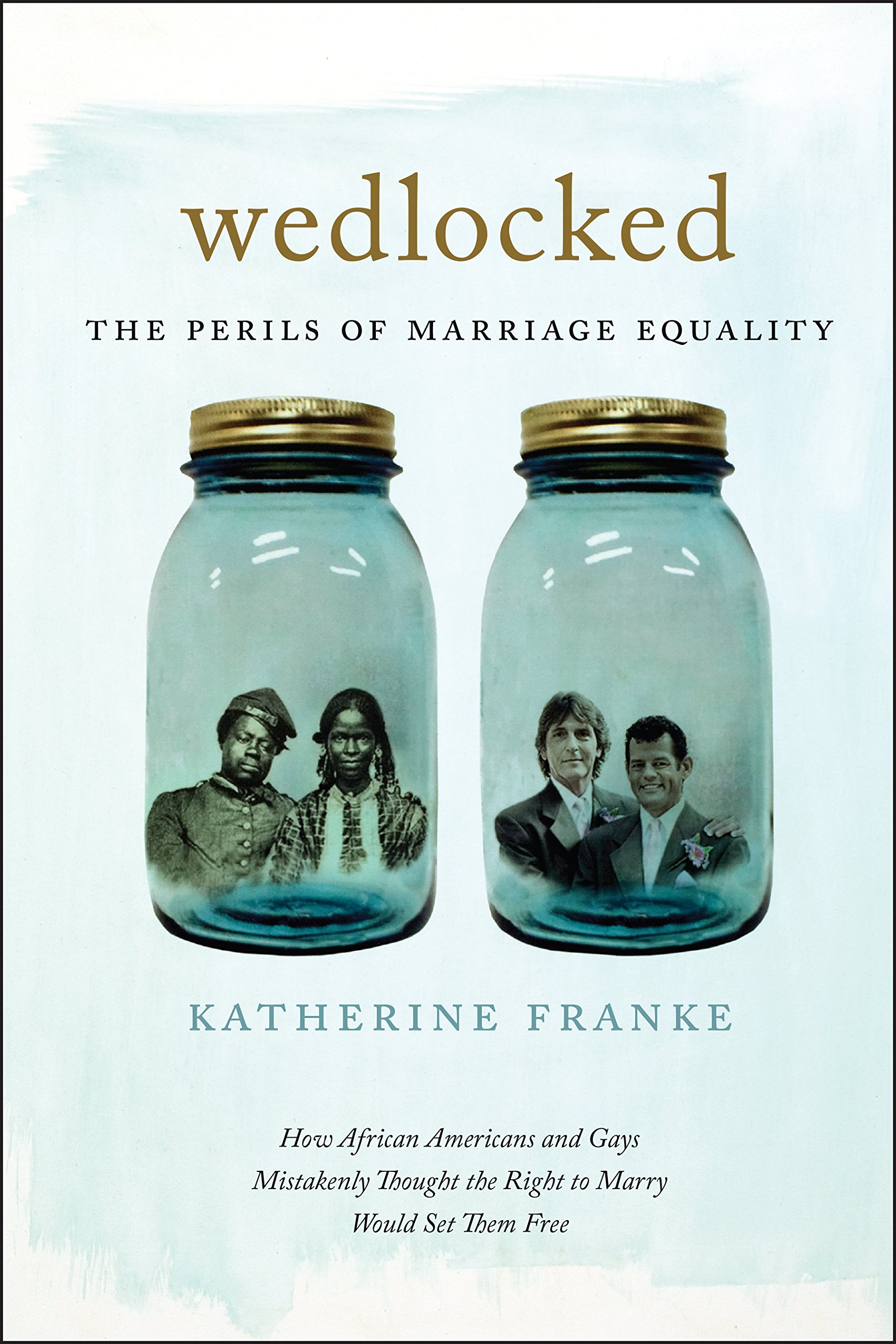

Comparing African-American rights with LBGT rights is risky. Is it too strong to say that every group and individual with a grievance feels free to compare their plight to that of people-of-color’s? Everyone’s pain is real, absolutely and unequivocally, but the stories don’t always line up. My argument is illustrated by the two couples portrayed on the book jacket.

One couple is unsmiling, a Black man newly freed so he can serve in the Union Army in Kentucky, a slaving state which nonetheless supported the Union during the Civil War, and his wife or partner who he may have had to leave behind on a plantation. Punishments endured by left-behind (not abandoned) wives were often more vicious than anything they previously experienced. The American businessman will stop at nothing to safeguard profits, and slave owners were American businessmen. The other couple on the book jacket looks like Adam and Steve, that winsome twosome feared and sneered at by evangelicals, the guys who walked hand-in-hand out of the Garden of Eden into nice suits, prosperous jobs, gym memberships, and a timeshare on Fire Island.

Sulzbacher Professor of Law and the Director of the Center for Gender and Sexuality Law at Columbia University, Katherine Franke is cognizant of the leap inherent in her comparison. Her purpose in writing the book is to warn against modeling same-sex marriage on heterosexual marriage. That would be like all lesbians styling our hair in ringlets or all gay men wearing dad jeans. Her research was coincident with growing national awareness of same-sex marriage, making Wedlocked relevant, imperfect, and valuable.

“Marriage, it turns out, is one way a society signals new acceptance of a previously outcast group,” she writes. Thus the first three of five chapters focus on marriage rights in relation to Emancipation, when literacy wasn’t prevalent and marriage certificates were relatively costly. Family units, however, were expansive and often more creative and adaptive than a white norm. Alas, sociological reports were issued on “the Black family.” Wedlocked is on safest ground when this research is simply discredited, as in the influential Moynihan Report of 1965 which maintained a “tangle of pathology” in said family. Though immediately declaimed, the report was heeded by law-making bigots as well as unimaginative law makers.

The final two chapters cover analyses and case studies of families in queer communities. There have been grievous legal problems, here, too. Many of a different sort. Heather had two mommies, sometimes two mommies and two daddies, sometimes two daddies and an out-of-state surrogate who kept tabs on her offspring. “Lawyers serving the lesbian and gay community now have a booming practice…” Some of that involves prenups allowing couples to “opt out of the most basic rules of marriage.” To her credit, Franke is aware of deadbeat dads and jilted first wives and is unwilling to see the law so transformed that straight women and their children are again at risk. “I am loath to allow same-sex divorces to open the door to weaken the gender-justice enhancing mechanisms in the current rules of divorce.”

As if Wedlocked were building a legal argument, Franke sums up a vital difference between her two groups near the book’s end:

The stories in this book, holding up side by side two experiences of newly won rights to marry, help us see how racial difference is a difference more indelible than that of sexual orientation. African Americans’ relationship to marriage, particularly compared with that of same-sex couples, shows us how fixed the signature of racial inferiority is for black people in American culture. No appeal to decency, tradition, or respectability can overcome the logic of difference that structures racial identity in this country.

Wedlocked’s mission statement is laid out is its appendix, “A Progressive Call to Action for Married Queers,” a list of points to consider before patterning a partnership or law on the old ways. For instance: “3. Think hard about the degree to which you are expecting to have it all when you marry on terms that work best for you, but that doing so may undermine important advances in gender equality for others.” Don’t compromise anyone’s rights or dignity to appease the right.

Finding new methods to live and perform our lives is a privilege. Two creative communities, Black and queer, have, by necessity and choice, pioneered ways for everyone. We have a Black president—that happened. We are legal—that happened. Coexistent with mind-boggling cruelty, we move forward.

Wedlocked: The Perils of Marriage Equality

By Katherine Franke

New York University Press

Cloth, 9781479815746, 288 pp.

November 2015