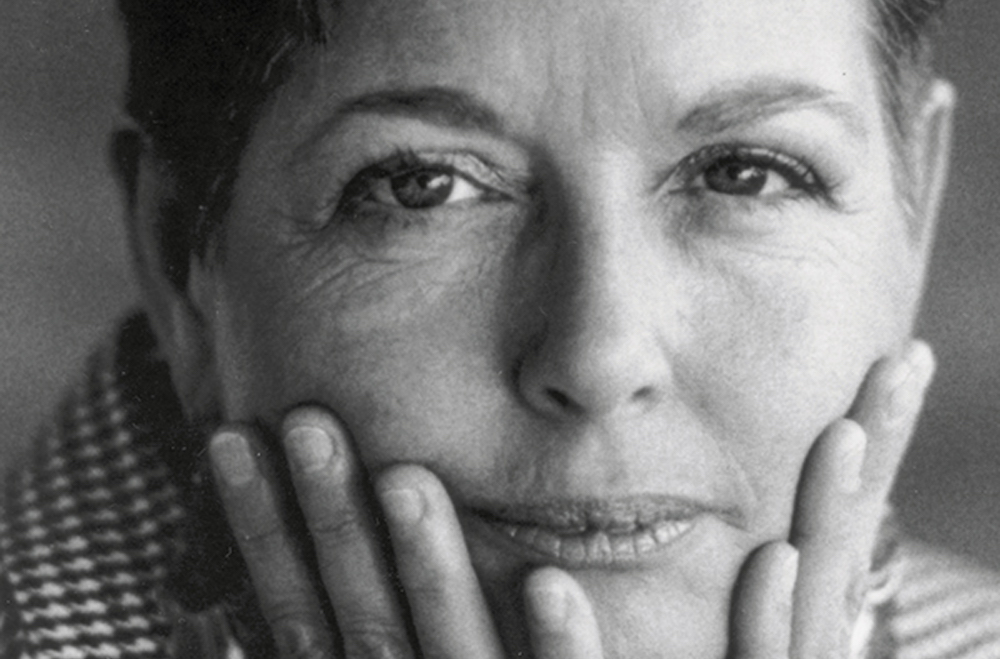

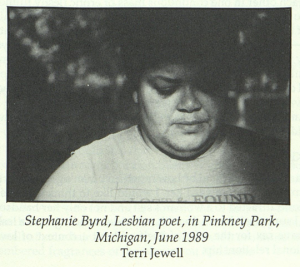

What Remains: Remembering Michelle Cliff, Beth Brant, and Stephania Byrd

Author: Julie R. Enszer

August 4, 2016

Is a woman alone a lesbian? Can a woman be a lesbian in solitude? Is lesbian an identity available in isolation? Or is lesbian only apprehensible when another woman is—or a community of women are—present? Perhaps there must be the pulse of another woman proximal for desire to exist. Perhaps there must be another woman to desire. A woman to reciprocate that desire. Perhaps lesbian only can be defined, embodied, discernible in the presence of at least two women. Perhaps it is in the sharing, the synchronizing of two hearts, two pulses, two breaths that the entire notion of lesbian comes into being. Or perhaps lesbian only comes into being in a community of other women. Perhaps an alchemy of many women brings lesbian—and lesbians—into being. What makes a lesbian? What creates the possibilities of love, sex, sensuality, community, and camaraderie between women? These quests animate some of the great lesbian literature produced over the past century. These questions also witness the lives of three great lesbian-feminist writers: Michelle Cliff, Beth Brant, and Stephania Byrd. All now of blessed memory, though their work—their pulse—remains.

It would be so simple to let other fill in for me.

So easy to startle them with a flash of anger

when their visions got out of hand

—but never sustain the anger for myself.—Michelle Cliff

The night Omar Mateen killed forty-nine people at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, Michelle Cliff died. Her partner’s son told me she died of a broken heart. I did not ask, What broke her heart? It was so simple to fill in answers. What broke her heart? The death of her life partner, Adrienne Rich, on March 27, 2012? The mind leaps to the cause of a broken heart as the loss of the beloved; and, of course, that explanation makes sense. How does one live on when the object of one’s affection, the daily extension of one’s self and one’s life for over thirty years, is suddenly gone forever?

Cliff and Rich met in 1975. Cliff was an editor at W. W. Norton; Rich was an author. Imagine the chemistry that brought them together. How palpable was the desire they had for one another before the relationship took flight? Did their co-workers feel the spark between them? Did it bubble slowly, a smooth simmer of desire before explosion or was the flame immediate? Hot, sexy, searing? There was passion, then life. A long life. Together.

It was around the time when Cliff and Rich met and forged their life-long partnership, that Cliff started writing. She told Opal Palmer Adisa in 1994 that in the mid-seventies, she wrote “Notes on Speechlessness.”

[I ] was involved with a group of women in New York who got together and discussed their works. We met once a month, and each person had to present something—and it was my turn. I was terrified, and I had a hell of a time just speaking. I was shy and tongue-tied a lot of the time. I didn’t know what to do, so I thought I’d write something and just read it, because that would be easier than speaking. So I wrote this thing about feeling speechless.”

That thing, that essay, lead to a second one, “Obsolete Geography.” These pieces became the kernel of Cliff’s first book, Claiming an Identity They Taught Me to Despise (Persephone Press, 1980).

In 1981, five years into their life together, Cliff and Rich purchased Sinister Wisdom from the founding editors Harriet Desmoines and Catherine Nicholson for $5,000. From their home in western Massachusetts, they published eight issues of Sinister Wisdom, number 17 through 24, between the summer of 1981 and the summer of 1983. A significant issue published by Cliff and Rich was Sinister Wisdom 22/23: A Gathering of Spirit / North American Indian Women’s Issue, edited by Beth Brant. A Gathering of Spirit was a crucial articulation of feminism in Native women’s communities. As a whole, Rich and Cliff’s editorship of Sinister Wisdom was enormously influential.

In the first issue they published, Cliff and Rich each wrote a separate “Notes for a Magazine.” “Notes for a Magazine” is the editor’s column in Sinister Wisdom, sometimes reflecting on the material in the issue, sometimes a column considering broader movement issues, sometimes an administrative update on the journal. In Sinister Wisdom 17, Cliff reflects on how “lesbian/feminists must work to rededicate ourselves to a women’s revolution” and situates Sinister Wisdom as having a crucial role in that revolution. Cliff concludes,

I approach this editorship with a certain degree of ambivalence. I am a thirty-four-year-old woman. A lesbian. A woman of color. I have just begun to write, and I am selfish about my writing and my time. But I have made a lifetime commitment to a revolution of women. I want to serve this revolution. And I want this revolution to be for all women. I want Sinister Wisdom to continue to be informed by the power of women. I want to make demands on this magazine, and I want other women to make demands on it also. I want these demands to include courage and vigilance. Theory and nourishment. Criticism and support. Anger and love.

Cliff’s opening salvo as co-editor of Sinister Wisdom captures the revolutionary zeal of the women’s liberation movement and Sinister Wisdom’s role in fomenting and nurturing the movement. Cliff’s words also reveal her vision for the journal: nurturing the dynamic tension between criticism and support. Cliff’s first “Notes” also provide a wonderful glimpse into the mind and commitments of a young writer, one who would contribute many important novels to our world.

When Rich and Cliff assumed the editorship of Sinister Wisdom, Rich had been living with rheumatoid arthritis for thirty-three years. While together they made all editorial decisions, Rich noted in her final “Notes for a Magazine” that Cliff operated as the “managing and sustaining editor, whose dedication, skill, and energy kept the body and soul of Sinister Wisdom together.” The time and skill required to be managing and sustaining editor successfully cannot be underestimated; yet Cliff’s work was not always recognized. Rich noted that it was “truly ironic that some correspondents and contributors chose to assume that I was the ‘real’ editor, or the only one.” The diminishment of Cliff’s work, of her labor on behalf of Sinister Wisdom and lesbian-feminism, must have been painful, disheartening, demoralizing.

Regardless of some people’s perceptions, editing Sinister Wisdom was a true partnership for Cliff and Rich. Cliff’s contributions to the journal should not be underestimated. In her final “Notes for a Magazine,” Cliff reflects both institutional and political concerns for lesbians. She wrote, “We must give all of our time and money (those of us who have it is always understood) to those institutions we care about, or else this movement will become only a pastime for women who can afford it, and not something geared to make radical change in the lives of sisters everywhere.” (Sinister Wisdom 24, p. 8). Cliff’s comments, rooted in the daily operations of the journal, are an important reminder of the importance of involvement in community institutions. They are as meaningful today as they were in 1983.

After passing the editorship of Sinister Wisdom to Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Michaele Uccella, Cliff’s work as a writer blossomed. Her first novel Abeng (1984) was widely praised as was its sequel, No Telephone to Heaven (1987). Set in Jamaica, these two novels explore the life of the protagonist, Clare Savage, with extraordinary lyricism and naturalism.

Cliff described growing up in the oral tradition of Jamaica to Adisa:

I come out of an oral tradition, and I come out of a colonial tradition in which we are taught that the “novel” was defined in such and such a way—a rigid definition. We come from an oral tradition that encompasses the telling of history, dreams, family stories, and then we also have the European idea of what a novel is. I have always written in a non-linear fashion. Another thing I owe to Morrison is her statement in Beloved that everything is now. Time is not linear. All things are happening at the same time. The past, the present, and the future coexist.

Cliff’s third novel, Free Enterprise (1993), continues to mine history through the story of Mary Ellen Pleasant and her support of John Brown and the revolution to end slavery. Cliff told Adisa:

I started out as an historian; I did my graduate work in history. I’ve always been struck by the misrepresentation of history and have tried to correct received versions of history, especially the history of resistance. It seems to me that if one does not know that one’s people have resisted, then it makes resistance difficult.

In spite of the successes of Cliff’s earlier work, her next novel, Into the Interior, struggled to find a publisher. In a 2008 Lambda Literary interview with Cliff corresponding with the release of what would be her final novel, Cliff said:

Getting Into the Interior published took quite some doing. It’s been out there for at least 10 years, and most rejections—from mainstream as well as small presses—have been unimaginative to say the least. It has been judged “too challenging for today’s audiences,” and “too experimental,” etc. In these times of dumbing down perhaps not surprising but depressing nonetheless.

When the University of Minnesota Press published Into the Interior, the context for lesbian-feminist writers, for feminist women of color writers, for women’s writing engaged in cultural productions as an aspect of radical social change, a context which embraced writers like Cliff, consuming their work with passion and fervor, had started to fray. Cliff, of course, helped to create this context through her editorship at Sinister Wisdom. In addition to lesbian-feminist journals, feminist bookstores, newspapers, coffeehouses, and communities of readers surrounded writers like Cliff, eager for their work, passionate about books and the consciousness changes they promised, willing to journey with writers through new narrative and lyrical terrains. This dynamic context nurtured Cliff and writers like her during the 1980s and 1990s.

Changes in book publishing, book sales, communications networks, and feminist and queer movements during the 1990s and 2000s adversely effected writers, including Cliff. Their audiences, once identified with physical spaces in the world, fragmented; the grassroots publications that published their work, reviewed their books, and promoted their readings shuttered, one by one; they lost their ability to sell enough books to support a commercial enterprise.

Loss was not new to Cliff. Her novels all explore loss and the challenges of living beyond losses. In her influential essay, “If I Could Write This in Fire, I Would Write This in Fire,” Cliff writes, “Someone once said the loss of your country is the greatest loss you can suffer, save the loss of a child.” Cliff’s work explores the loss of country repeatedly. Loss—and equally important imaginative efforts to regain or replace what has been lost. Both are powerful elements of imagination and imaginative texts—poetry, stories, novels, plays. They invite us to remember anew, to recreate with different outcomes, with possibly more hope, more joy, more humor.

Yet, in spite of the respite literature offers, at the end of her life, Cliff lived a loss of context. Our world had lost a context to understand her work. This loss, another heart break.

In the days following Cliff’s death, I have been haunted by my unspoken question: What broke her heart? Yes, Cliff’s heart must have been shattered by Rich’s death, but she also endured a myriad of other losses as well. Though Cliff’s work is still in print, the community that surrounded and embraced her work in the 1980s and 1990s is not organized in the same ways. It is less able to communicate a communal embrace of an author. The New York Times obituary offered one remedy for a spell. Women remembered Cliff. They praised her work. They held her memory with words and light and small celebrations. It was good. I imagined these celebrations mending with the smallest of stitches her broken heart.

II.

Sky Woman had a peculiar trait: she had curiosity. She bothered the others with her question, with wanting to know what lay beneath the clouds that supported her world. Sometimes she pushed the clouds aside and looked down through her world to the large expanse of blue that shimmered below. The others were tired of her peculiar trait and called her an aberration, a queer woman who asked questions, a woman who wasn’t satisfied with what she had.

–Beth Brant, “This is History,” Food & Spirits

In December 2014, I received an email message from Beth Brant’s son-in-law. Beth’s health was failing; he had recently learned of the friendship that Beth and Michelle Cliff shared during the 1980s and 1990s. He wanted Beth to reconnect with her. He wanted to cheer her amid the sorrows of an ailing body. He wanted her to remember who she was: a revered lesbian-feminist writer.

Beth Brant was the first writer I knew personally. I was working with my friend and colleague Shannon Rhoades on the gay, lesbian, bisexual newspaper, Between the Lines in Detroit. The paper published monthly. Shannon ran it out of the home we shared near the old Tiger stadium. As a statewide newspaper, Between the Lines received a steady stream of queer and feminist books published around the United States. Each day brought stacks of newly minted titles to our door. It was readers’ heaven. I still remember evenings when all of our housemates gathered and read the steamy passages from the newest Naiad romance or political screeds from galleys of forthcoming books by Urvashi Vaid, Torie Osborn, Michaelangelo Signorile, and others. When Brant’s third book Writing as Witness: Essay and Talk was published in 1995, we were thrilled to learn that she lived in suburban Detroit. I remember us squealing a bit, in the fangirl way we regarded writers, with the glee and reverence reserved for iconic feminists. I remember my heart beating more quickly as my mind immediately wondered, Could we meet her? Could I talk to her? After reading A Gathering of Spirit as undergraduates, both Shannon and I recognized that we were in the same geography as a literary genius. As if for the first time, we knew we were living within minutes of a lesbian-feminist icon. We were giddy. We were breathless.

A Gathering of Spirit was first published as a special double issue of Sinister Wisdom. Sinister Wisdom 22 / 23 carried the title, A Gathering of Spirit and the reading line, North American Indian Women’s Issue. Michelle Cliff and Adrienne Rich published the issue in 1983. During the first half of the 1980s, feminist writers, editors, and publishers produced an extraordinary amount of material that elaborated intersectional identities. That is, feminist and lesbian writers brought words and language to the meanings of different racial-ethnic categories and to the various ways of engaging feminist ideas depending on one’s situated location in society. This Bridge Called My Back, published in 1981 by Persephone Press and later reissued by Kitchen Table Woman of Color Press, gathered voices of women defining woman of color as an identity and elaborating coalitional politics for African-American women, Latina women, Native American women, and Asian American women. Evelyn Torton Beck brought a similar sensibility to questions of race, ethnicity, privilege and power for Jewish women in Nice Jewish Girls, published in 1982 by Persephone Press. Anthologies played an important role in the elaboration of these intersectional identities, but single-author books were important as well. Spinsters Ink published Kitty Tsui’s The Words of a Woman Who Breathes Fire and Paula Gunn Allen’s The Woman Who Owned the Shadows, both in 1983; Crossing Press published Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name in 1982. Discussions about race and identity were then, as now, powerful and important. Books, particularly feminist press books, were a crucial part of these conversations. Into these discussions, entered Beth Brant with A Gathering of Spirit.

Sinister Wisdom 22 / 23: A Gathering of Spirit is a thick issue, 226 pages. Deciding to edit the issue was a struggle for Brant. The idea arose when she was visiting Cliff and Rich at their home in Montague, Massachusetts in January 1982. Brant writes in the introduction, “I asked if they had ever thought about doing an issue devoted to the writing of Indian women. They are enthusiastic, ask me if I would like to edit such a collection. There is panic in my gut. I am not an ‘established’ writer.” She confides later that she grappled with the question and the “complicated realities of my life. I am uneducated, a half-breed, a light-skinned half-breed, a lesbian, a feminist, an economically poor woman.” Then she thinks about “responsibility, about tradition, about love. The passionate, stomach-tightening kind of love I feel for my aunts, my cousins, my sister, my grandmother, my father. And so, I am told—it is time to take it on.” (Beth Brant, “Introduction,” Sinister Wisdom 22/23: A Gathering of Spirit, 5.) A year and a half and many rolls of stamps later, A Gathering of Spirit entered the world. Brant notes in her introduction that material support from Sinister Wisdom (paying for stamps, flyers, and photocopying) enabled her to do the editorial work.

Like other issues of the journal, A Gathering of Spirit featured all manner of creative literary expression: poetry, prose, essays as well as images, photographs and drawings. Contributors include Linda Hogan, Paula Gunn Allen, Wendy Rose, Luci Tapahonso, Chrystos, Joy Harjo, Barbara Cameron, Nila NorthSun, Jaune Quick-To-See-Smith, and many others. Brant describes the contributors in her introduction:

We are here. Ages twenty-one to sixty-five. Lesbian and heterosexual. Representing forty Nations. We live in the four directions of the wind. Yes, we believe together, in our ability to break ground. To turn over the earth. To plant seeds. To feed.

Brant continues the poetic cadence of the previous sentences all of the way to the end of her Introduction. It is a beautiful passage to read. While she acknowledges the challenges of editing A Gathering of Spirit from the earliest conception of the issue to its completion, it was sacred work. Work that fed her spirit.

Shannon and I encountered A Gathering of Spirit not as an issue of Sinister Wisdom, but as a trade book from Firebrand Books. Nancy Bereano reissued A Gathering of Spirit in the spring of 1989 after the Sinister Wisdom issue sold out. Shannon and I read it in a women’s studies class, beholding it as new, beautiful. After reading A Gathering of Spirit, I found the more of Brant’s work.

Brant began writing at the age of forty. Born on May 6, 1941, Brant was a Bay of Quinte Mohawk from the Tyendinaga Reserve in Deseronto, Ontario. She published widely; her work appeared in numerous Native and feminist journals and anthologies in Canada and the U.S. Bereano published Mohawk Trail, Brant’s first book, in 1985 as one of the first three books from her new publishing company, Firebrand Books. In 1991, Bereano published Brant’s Food & Spirits, short fiction. Press Gang released the book in Canada. In 1994, Women’s Press in Toronto published Writing as Witness. McGilligan Books published her collection of oral histories of Tyendinaga Elders, I’ll Sing ‘Till the Day I Die, in 1995.

Brant was the two-time recipient of the Michigan Council for the Arts Creative Artist award. She received an Ontario Arts Council award, a Canada Council grant and was a recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship. She was the mother of three daughters, Kim, Jennifer, and Jill, and a grandmother. She lived in Detroit for most of her life and spent over twenty years partnered with Denise Dorsz, though the two separated.

I met Beth in 1995 when Writing as Witness published. I interviewed her for Between the Lines after a reading celebrating the release of the new book at A Woman’s Prerogative, the feminist bookstore in Ferndale, Michigan. In the article, I wrote that Brant “is one of the unrecognized gems of Detroit.” Brant discussed her writing process, her political vision (she worried about the conservative tone in the country at that time, asking these questions “Why do we want to be a part of a system that despises us? Why do we want to sit at a table and eat with these monsters?”), and her voluble metaphors: cooking and animals.

After the article published, Beth invited me to her home for dinner. Denise cooked. I spent a handful of afternoons and evenings with Beth. We talked about writing and writers. She shared books and journals with me. Her mind demonstrated to me a life of a writer. I treasure that time we had together and my memories of it. Then, I met the love of my life and moved away from Michigan. We lost touch until her son-in-law emailed me. I sent her a newsy letter with a stack of issues of Sinister Wisdom. I wrote of our menagerie of animals. I wrote of editing Sinister Wisdom. I described A Gathering of Spirit as a touchstone. It is. I wrote, “Trying to keep Sinister Wisdom alive—and the dreams it has of lesbians and lesbian communities. Dreams, often I suppose dashed by realities. Isn’t that the case of dreams always? Anyway, I edit it and dream.” I did not receive a response from Beth to that letter. She died on August 6, 2015.

Like Cliff, at the time of her death, Brant had lost her context. She died surrounded by her family—daughters, sons-in-law, grandchildren—but she lost contact with the writers, artists, and activists who were an important part of her world. After her death, I wondered, How do we hold on to the connections that we make in the world? How do we keep friends close? How do we accept support and kindness and love at the times when we are most vulnerable?

I have been searching for answers to these questions in Brant’s work. I have not found them, but I have clues. Beth dedicated A Gathering of Spirit in three ways. First, she named Anna Mae Aquash (Micmac), a Native woman who was “raped, shot in the head, thrown down an embankment.” Brant names her as “a casualty of the war between the FBI and the Indian People.” She also names Saralinda Grimes (Cherokee) as a “lesbian, resister, organizer” who died in Tilden Park, Berkeley, California from “an overdose of morphine and codeine.” Brant names her as “a casualty of the war against women, against gays, against the Indian People.” Finally Brant dedicates the book to “All Indian women who have survived these wars and live to tell the tales.” In the first two dedications, Beth calls into being women we have lost; in the third, she affirms women living, struggling, surviving, speaking. Language, experience into speech, is one way we hold our connections in the world. Reading is one way we keep friends close. Memory is one way to keep the context of the past present, inviting us to imagine, to create new future contexts.

After Brant’s death, I am overwhelmed by loss: the loss of her voice, the tales that died with her. There was no obituary in The New York Times for Beth Brant; at her request there was not an obituary in local papers. She passed from this world to the next without context, without immediate literary reverence. In October 2015, a group of writers and activists in Toronto held a public gathering to honor Brant’s life and work. They called her memory into being. They honored “Beth in the spirit that she honoured us.” This August 6th, the first yartzeit of her passing, may more honor her work and her life.

Sometimes still I dream of sitting in her kitchen talking. Sometimes still I dream her laughing, then sighing with pleasure. Lesbian, resister, organizer. When I dream and feel love from elders, I know Beth is near. When I wake, the work before me is clear.

III.

A poem will find its way to my sister soldiers

as they lie quietly waiting for danger to pass.

–Stephania Byrd

Stephania Byrd was never recognized in the same ways as Brant and Cliff. She published two collections of poetry, 25 Years of Malcontent (Boston, MA: Good Gay Poets, 1976) and A Distant Footstep on the Plain (1981). I happened upon 25 Years of Malcontent in my research. The book electrified me. I wanted to find her, to speak to her about her work. I located Steph through the extraordinary literary network of Lisa C. Moore of Redbone Press.

Steph and I spoke on the telephone a handful of times and worked on a few collaborative projects together. I was publishing chapbooks online at the LesbianPoetryArchive.org. Steph agreed that I could publish an online edition of both her books. I wrote a brief introduction. She wrote an afterword about the publishing history of her two books. In it, she said,

It is incumbent upon me to publish my poetry because a poem will find its way to my sister soldiers as they lie quietly waiting for danger to pass. It has the capacity to buoy one when she thinks she may perish it gives her strength to move on.

Steph understood how poems worked in the world and how they made a difference in people’s lives, in lesbians’ lives.

When we released the ebook of her work, the Poetry Foundation published a dialogue between us. This interview was a selection from a much longer dialogue that Steph and I had about her work and its meanings. Byrd was thrilled with these projects. They brought her work back into public dialogues about poetry and its meanings. Some of our conversations over email and on the telephone were never published. I returned to this material thinking about Byrd’s life.

I asked Steph to tell me about how she wrote the poems of 25 Years of Malcontent. She replied:

From 1973 until 1974, I was unemployed, so I used to draw and write when I got home from job hunting. When I finally got a job, I was a gay and lesbian youth advocate at the Charles Street Meetinghouse on Beacon Hill in Boston. This program was funded with Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (L.E.A.A.) money. Barney Frank was around and Rev. Randall Gibson, the pastor of the Charles Street Meetinghouse. Gibson was a physicist turned preacher. Frank was, in my opinion, the connection to the wealth Washington, D.C. represented and still represents. Around that same time, I began to go to black feminist discussion groups. I met the photographer, Constance Miller Engelsberg, who taught me how to use the camera lens.

Hearing that she was an amateur photographer shed light on the images she uses in her poems. I asked her if photography informed the book.

Yes, I was fascinated by the myriad of contrasts I was able to capture on paper and wanted to translate that into verse. While I was writing these poems and working on the photography, I was still reading Latin and was growing restless with my reading Medieval Latin—I did not hear it like I did “Dido’s Cave” in Book Six of the Aeneid.

I first encountered Dido’s cave in my senior year of Latin in high school. I remember my Latin teacher, a Quaker woman, whose son gave me piano lessons from fifth grade until tenth grade. She was my only advocate during my high school years. I digress. Upon translating the Latin about Aeneas and Dido’s sexual conjugation after they take shelter in the cave, my Latin teacher responded to a question by writing “vagina,” Latin for cave, on the board. Had this happened outside of school, I would have shouted, “yes.” To paraphrase Fairclough’s translation of some lines from Book IV, I was “on fire with love and drawn the madness through my veins.” At that time I was in love with a woman a year older than I; she lived in Saratoga Springs, New York and we became platonic friends. I wanted to enter Dido’s cave figuratively and literally.

Steph was a student of the classics. She studied Latin and encouraged me to shore up my knowledge of canonical literature (to her disappointment, I did not.) My research is in queer and feminist publishing, so I asked Byrd to tell me the publishing story of 25 Years of Malcontent at the Good Gay Poets Collective.

The two gay men I dealt with were Charlie Shiveley and Rudy Kikel. Both Charlie and Rudy were sweet. I cannot say that of everyone at the Good Gay Poets Collective. Some of the other men in the Collective believed publishing with the spelling of my first name as it appears on my birth certificate, Stephania, was pretentious. They insisted that I publish with the first name Stephanie. This was not the first time the spelling of my first name was challenged. When my mother enrolled me in kindergarten, those people at the school changed the spelling of my name from Stephania to Stephanie and told my mother she did not know how to spell my first name!

In spite of the issues of my good name, I was presented with an opportunity to publish 25 Years of Malcontent, and I decided the spelling of my name was not going to prevent me from seizing the moment. When I was given a deadline for handing in 25 Years, I met it.

I believe that the collective did not want to publish my work, but the work of my gay brother, Kenneth Dudley instead. Kenneth Dudley used to recite his poems from memory; he flowed. The Good Gay Poets Collective kept waiting for Kenneth’s manuscript. He kept putting it off. When it came down to sending the work to the typographer, Kenneth finally came out with his no and without explanation. He backed out after the collective had already prepared my manuscript for publication. I believe that for Kenneth putting his work on paper was a metaphoric act of confinement for him. He also saw himself as a griot and wanted someone other than him, to write it down.

My relationship with gay men presented problems for some lesbians because of the separatism among some lesbian-feminists, but Kenneth was my brother just like Normal X. I often wondered why Normal X did not try to get his work published. Normal was a member of the short-lived X Poetry Collective with Kenneth and me. I asked him once on our way to a lesbian and gay bar in the Combat Zone called The Carnival why he didn’t publish. He said he did better hustling…writing and publishing were too straight. These brothers were poets but their disdain for putting their words to paper was, in retrospect, their way to control their words’ power.

I would say both of these black gay men were griots and felt their words were not for sale. The griot is found throughout West Africa; male and female, they keep oral traditions that are enjoined with the practice of writing begun during the thirteenth century of the Common Era in Arabic.

Rereading her responses, I wish that Steph and I had talked more, that I had asked more questions. Her words begin an important history of Good Gay Poets and the X Poetry Collective, though I am left wanting more. I never asked about the work of Kenneth Dudley and Normal X. What happened to them? What happened to their work? What happens to our history when one of its keepers dies?

One of the things I love about Steph’s poetry is how she wrote about lesbian sexuality, particularly the combination of sexuality and violence. In “Love Poem,” she wrote,

You suck my vagina

draining me

of pus and bile

offering your mouth

as antidote

Much of the poetry by lesbians in the 1970s is celebratory of lesbian sexuality—lots of flowers and ecstatic engagements. Steph celebrate lesbian sexuality certainly (this poem ends with the lovers “sharing immortality”), but she also reflected sexuality as a site of violence and distress. In this poem, instead of the usual sugary sweetness or flower nectar, pus and bile come from the vagina. She told me:

During the period of the 1970’s, I was plagued by words, “sick” and “diseased,” from those who heard me speaking of lesbian sexuality. I say these words specifically because “dirty” was not a word I heard. The first time I heard those words was from a black woman in social services when I went to advocate for foster care for a young gay man, who was hustling. I believe people become blinded by the power inherent in lesbian sexuality; so I crafted imagery associated with power when it sees the act of woman–fucking. Woman–fucking is the antidote for those who would call lesbians sick and diseased.

I continue to revel in those words of Steph’s. She created in her own life an antidote to lesbophobia.

Steph and I talked about the themes in her second collection, A Distant Footstep on the Plain. She told me:

One thematic element is black lesbian identity and its challenges. The tone in A Distant Footstep is at times angry; and at other times, it is sardonic. By this I mean there are times I could laugh myself to death at the folly of women, regardless of age, color, or sexual identity. I found and still find our folly as women, and I am as guilty as all women of folly, hilarious. Perhaps, this is why I am drawn to women, physically and emotionally. Terri Jewell had the ability to make me laugh until my stomach hurt. I am fortunate to have had women in my life with this kind of power. So sex is another thematic element. I think sex is a hoot and a half!

Why did I love Steph? Perhaps because I too, think sex is a hoot and a half. Though of course I have written seriously about Byrd and her work. Her two collections of poetry demonstrate a wider vision of Black lesbian poetry in the 1970s and 1980s.

Byrd’s chapbook, 25 Years of Malcontent, from Good Gay Poets circulated widely in lesbian and feminist communities. At a December 1977 panel titled Lesbians and Literature chaired by Julia Penelope Stanley at the annual Modern Language Association Convention in Chicago, Illinois, four women spoke: Mary Daly, Audre Lorde, Judith McDaniel, and Adrienne Rich. Rich presented last. She concluded her remarks on silence “as a crucial element in civilizations” (all of the presentations were printed in Sinister Wisdom 6; the Rich quotation is on p. 17) with two poems. One was by Emily Dickinson; the other by Stephania Byrd, who she described as “a 25 year old Black Lesbian poet.” Rich read Byrd’s poem, “Quarter of a Century.” The poem begins:

I’ll never know my real naming

Never know its origin

What would you call this high yellow

Born into uncertainty and schizophrenia

Born into a place where I have no say

I live with the ghosts of slaves

Whose blood still colours my dream

The poem concludes:

Bones say seek my naming in the East

swollen cracked lips tell me to turn home

grandmother warn me to turn away the alien ways of

what is white

For when these things are connected

Winding serpentine in hieroglyphs and

language

a name long evasive wandered and prophet

will be written in the stone.

When Byrd and I spoke, she described “Quarter of a Century” in this way:

I think of “Quarter of a Century” as my “drum beating” poem.

When I was ten, my parents and I were broken down near Pike’s Peak, Colorado. We had a nice firebowl dug and a homemade camper trailer off the ground. It was chilly and we heard the drum; we followed it to its source and it was troop of Boy Scouts. I was conscious of the drum’s sudden silence when we entered the circle and then our quick departure. The silencing of the drum was an affront to me and my family. My mother broke it down to me on the walk back that this was a state park and everyone had a right to be there. This was a revelation; it revealed not only my right to the drum, but also the power of the drum. I was singing in this poem, because I was happy in spite of what I still call shit.

You beat the drum when you want people to listen to what it is saying. I was beating out my names, unspoken except by those who cared for me. My drum-beating was a call to women to open their minds and hearts to what I was saying. Drumming also has ritual significance, especially to those women who are seeking answers beyond the page.

Women who are seeking answers beyond the page. This sentiment connects Byrd and Brant and Cliff. They wrote and spoke to women on the page and beyond the page.

Stephania Byrd was born on July 10, 1950 in Richmond, Indiana. She studied Latin at Ball State University and completed her bachelor’s degree at Michigan State University in 1989 and her master’s degree in 1998 at Cleveland State University. Byrd was the beloved partner of Terri Jewell at the time of her death in November 1995. She was a Professor of English at Lakeland Community College in Kirtland, Ohio until she retired. Byrd retired when she fell in love with Pat Uribe-Lichty; Byrd moved to Pennsylvania to spend her life with Pat. She was so happy to have Pat in her life and experience love again. Although she had many health issues, her death on October 22, 2015 felt sudden. Her partner Pat survives her. There are many conversations I wish we had time to have.

IV.

I do not know if a woman alone can be a lesbian. I do not know if a woman can be a lesbian in solitude. I do know that I was alone when I first read the works of Michelle Cliff, Beth Brant, and Stephania Byrd. I do know that, reading their books, encountering their words, I felt the pulse of lesbian throughout my entire body. They spoke to me and said, This life, these lesbian words, these lesbian desires, these lesbian truths are yours. And I accepted their words, their works, their desires, and their truths as my own.

Recently, Cheryl Clarke told me, “Without the feminist press, you would not have heard of Cheryl Clarke.” During the three decades following the women’s liberation movement, feminist publishers released hundreds of books by lesbian-feminist writers. Some of these books reached broad readerships. Authors like Dorothy Allison, Sapphire, and Alison Bechdel all started with feminist publishers. While it is thrilling how these authors have broken through to mainstream audiences, enjoying a wide readership and multiple accolades, there are dozens, even hundreds, of other writers whose work do not secure the same attention and praise. Cliff, Byrd, and Brant are three among these writers. The labor of Cliff, Byrd, and Brant are all implicated in the recognition of more popular writers. None of them would exist without the vibrant ecosystem that feminist publishers created. The context created for writers like Cliff, Brant, and Byrd was important; it helped to bring their work into being. The erosion of that context, the fraying of it, and even, yes, the loss of it, was a loss not only to readers and reading communities but to the writers as well. I believe all three—Byrd, Brant, and Cliff—felt the loss of context in the last years of their lives.

Attending to the deaths of Cliff, Byrd, and Brant, one marked in The New York Times, the other two marked by family, friends, and local communities, is one way to honor their literary lives and legacies. Marking their lives and deaths reminds us of the broad context that feminist and lesbian-feminist communities created for lesbians’ artistic productions. The reminder of this context, the narration of this herstory is a wish—a kiss—for a future of our own imagination, our own creations.

Cliff’s death, Brant’s death, Byrd’s death all brought sadness into my world. Sadness and important questions. What causes heartbreak? How can we hold on to the connections that we make in the world? What is the antidote to lesbian-hating? How do we write power? Remembering these three writers, speaking of them, writing about the work is a form of testimony. Like all lives theirs were filled with love and heartbreak, truth and beauty, pain and suffering, honesty and profound disappointments. In their lives, in their works, was a lesbian pulse. The heart, the blood, the spirit of women. The possibilities of love, sex, sensuality, community, and camaraderie between women. Now all of blessed memory. Their work, their pulse remains.

Michelle Cliff

November 2, 1946-June 12, 2016

Beth Brant

May 6, 1941-August 6, 2015

Stephania Byrd

June 10, 1950-October 22, 2015

Note: A small portion of the material about Cliff’s editorship of Sinister Wisdom is adapted from “Adrienne Rich and Michelle Cliff Editing Sinister Wisdom: ‘A resource for women of conscience’” (Sinister Wisdom 87 (Fall 2012), pp. 77-87.) This essay is dedicated to Tim Retzloff, a sustaining light in my life. Tim is an historian, archivist, and chronicler of queer history in Michigan. Tim collects obituaries of queer Michigan residents and holds their lives and stories for public memory; his commitment to collecting and writing was a beacon to me in a dark time creating the light needed to write this essay. Thank you, Tim.

Photo: Stephania Byrd via Sinister Wisdom

Photo: Michelle Cliff via wmich.edu

Photo: Beth Brants via Firebrand Books