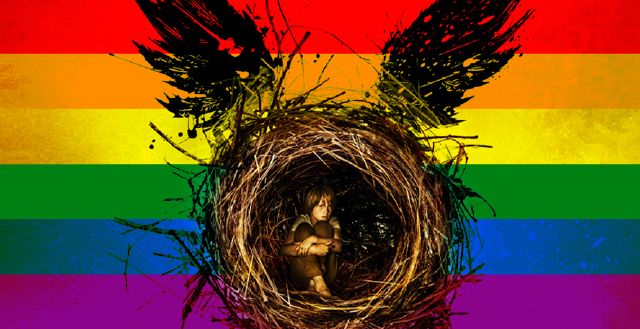

Harry Potter’s Gay Subtext, Why Trans Women Write, and More LGBT News

Author: Parrish Turner

August 5, 2016

In other LGBT news…

I don’t think one could have gotten through this past week and not heard about the new Harry Potter script book, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. Many have loved the book and many have spoken up about the homoerotic subtext which never becomes fully realized. Tariq Kyle breaks it down with minimal spoilers.

Instead, we’re left with another Harry Potter story that doesn’t directly show us a single member of the LGBTQ community. Sure, if she wanted to, J.K. Rowling could announce in a few years that [character name redacted for potential spoilers] is gay, but that 👏 just 👏 doesn’t 👏 count. Telling your readers and/or audience a few years later that a character has been gay this entire time doesn’t equal representation, because you weren’t representing that community when you wrote it.

It’s important that we represent the LGBTQ community with central characters that already exist in the main story arc, so that people reading or watching these stories understand just how normal the community is. If you announce that a character is gay after the story is over, you’re pointing out their differences and making it about their sexuality again, which singles them out as something different or odd. The point should be to make them equal to the heterosexual characters during the story.

At the time of writing this, we are still awaiting the release of Frank Ocean’s new album, Boys Don’t Cry. Hopefully, it is only a matter of hours…. Right? Right?

Topside Press has an upcoming writer’s retreat for trans women. In anticipation, Ana Valens wrote an essay for Bitch Media entitled “This is Why I Write: Almost All Stories about Trans Women are Written by Cisgender Authors.”

It’s the fact of what it means to live as a trans woman. It’s the way you carry yourself and the clothing you wear. It’s the late night drinking sessions and the summer picnics in the park. It’s the body heat of another trans girl cuddling against you, it’s your first time sleeping with another person as a woman. It’s the sum of every single experience you’ve had, that your sisters have had, and that your forbearers have passed on. It’s to live and love and—one day—die in a world that is uniquely your own, that the outside world simply doesn’t understand. How can I put all of those stories into words while doing them justice?

Tim Murphy’s novel Christodora has been optioned for a limited television series by Paramount TV. Ira Sachs and Mauricio Zacharias will be writing the adaptation.

Young adult books, especially queer young adult books, are really hitting their stride in the popular media. And young adult books have changed greatly over the years, often reflecting changes in our culture. Michael Waters explores this evolution in his essay on The Establishment.

Over a year since the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage across the country, novelist Matthew Griffin argues that it is time for our literature to reflect on what a gay marriage looks like:

Many have worried that marriage equality and the normalisation of gay culture may dampen the creativity with which many of us have lived our lives on the fringe, may fray the vibrant communities and families we’ve built when those we were born into rejected us. I hope that we will, instead of being dulled by the institution, bring the liberating creativity of gay life into it. We have now the opportunity to define marriage for ourselves. Here too the novel can be our lens, helping us imagine lives for ourselves, possible outcomes, to bring our own blurry, nearing futures into sharper focus while we still have time to shift course.

Darryl Pinckney’s essay in The New York Review of Books examines the relationship between the Black Lives Movement and the Police.

In TLS, Edmund White reflects on Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire.

At the time of the novel’s publication, many gay men were vexed by the satirical portrait, though now it seems perfectly acceptable. Gay critics are no longer prospecting for positive role models. What we have instead in Kinbote is a compendium of “period” gay images. The “Baron” (a fake title) Wilhelm von Gloeden’s staged photographs of Sicilian boys with cracked feet, peasant tans, hunger-bloated stomachs and coarse faces, wearing ancient Greek togas and laurel wreaths and holding papier maché lyres; Prussian porn and English gentlemen’s proclivities for willing, paid guardsmen; the aesthetes of Oscar Wilde’s day (a single tulip); the gay son of a famous womanizing king (Mad Ludwig and his royal father, lover of La Belle Otéro); the tennis champion Bill Tilden, whose spectacular playing made him famous in the 1920s – and whose paedophilia landed him in prison; “scoutmasters with something to hide”; idyllic romances with athletes and shepherd boys in the style of A. E. Housman, whose Shropshire Lad Kinbote admires above all other poems except for Tennyson’s equally fruity In Memoriam; the sailors so sought after as “rough trade” (non-reciprocating, drunk, heterosexual bullies): all are evoked here, a catalogue of male homosexual desire through the ages.

(image via Hypable)