Garrard Conley: On Surviving Ex-Gay Therapy, Writing His Memoir, and the Year in Queer Lit

Author: Todd Summar

June 20, 2016

“I remember in the 90s and even early 00s, the idea was still prevalent in popular culture and the media that gay sex equaled death. When you’re in this religious environment, it complicates it even further.”

At the age of nineteen, during his first year of college, Garrard Conley was outed to his family against his will. It’s a time in many people’s lives when they grow intellectually and explore their sexuality, but for Conley, it was even more complicated. His father was a Missionary Baptist preacher, and he was raised in a small, close-knit Arkansas town. Life was regulated by the Bible and the watchful eye of the people, both young and old, who surrounded him. Conley’s father gave him an ultimatum: attend a Christian “ex-gay” therapy program called Love in Action (LIA) or be disowned and cut off from his education. Frightened and ashamed, Conley chose to attend LIA.

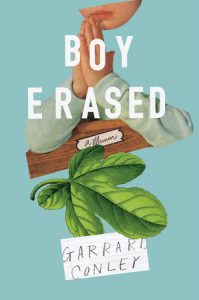

Boy Erased, published by Riverhead Books in May, is Conley’s account of the grueling experience he endured during his time at LIA. The intense scrutiny sapped Conley of his identity in what Charles Baxter called “an attempt at soul-murder.” However, Boy Erased is not an expose, not a self-help book or sentimentally sensational tell-all. Instead, it is a nuanced, sharply written work of art. Conley’s prose is evocative and lush, allowing the reader to understand the confusion and frustration endured, not only by him, but also his mother and father who, ultimately, regrettably, thought they were doing the right thing.

I spoke with Conley, who lives in Sofia, Bulgaria where he teaches, via Skype before he left for the U.S. to embark on his book tour.

What prompted you to start telling your story?

I was doing a Masters in Fine Arts in fiction at UNC Wilmington, but I’d enrolled in this nonfiction class and the teacher said, “You need to write about something in your life, and it’s best if it’s really dramatic.” I started to tell everyone about the two weeks [at LIA] and they said, “Wait, what?” I said, “Yeah, that’s what happened,” like it was no big deal. And they told me, “You have to write about that. That’s crazy.” I said to the group, “Well, if I write about it, you have to be honest and tell me if you hate my father.” They read it and said, “I don’t know how I feel about your father, it’s confusing.” And I thought, Yes, I can write it! That’s when I knew what the real question of the book was going to be, the question that everyone kept asking me. “How could any parent do this to a child?” I found that question nice to hear because I hadn’t thought about it in that way. But I also found it annoying because it was like, of course a parent could do this to a child. Do you not know what it’s like to live in Arkansas in the church? That’s where the book is. It’s not “How could anyone do this to a child?” It’s “How could anyone do this to a child? How did this happen, and how is this related to a larger spectrum of LGBTQ experience in the United States that still exists and is not going away any time soon?” At the time that I was living that experience in 2004, it was a terrifying time in the country. At the same time that I was trying to particularize my experience, I was trying to show how these well-meaning people bought that stuff. They didn’t just buy ex-gay therapy, they bought WMDs in Iraq, they bought everything that was being sold, and it was not necessarily their fault in some ways. This is not just about my family, it’s about a lot of families that were tricked.

You weren’t allowed to journal, write, photograph, or document anything while in the program, but there’s so much detail and reflection throughout. Could you describe the process of building all these details from your memory?

That was really hard for me. I had gone home the summer before I went to UNCW and found the Love in Action handbook in the bottom of a drawer. I said to my mom, “This is gold.” (Laughs) I had to just talk to my mom for hours about what I’d said during that time and what she could remember. She came in the first day of the program to see everything, so it was really helpful for her to say, “Okay, there were laminated 12 Steps on the wall, and it was weird, and there was this one bathroom in the hallway, and John Smid’s [former director of Love in Action] office didn’t have anything in it except an embroidered Bible verse.” As I started to focus in on really specific details, I built around them. As a fiction writer at the time, I thought, There’s no way I can enter the scene without details. With my dad, it was a little bit harder, not because I couldn’t remember. It was harder because there were so many memories. You can sort of tell that in the “Plain Dealers” chapter because it just goes in and out of different memories. All of that stuff just came back to me at the same time. I wrote that in a 48-hour period, and I feel like it’s true because it was just a singular writing experience that I’ve never had again.

The structure of the book is interesting because you intercut your two weeks at LIA with the period that led up to that point in alternating chapters. What drove the decision to structure it this way?

Everyone just kept saying, “It’s only two weeks, you’re fine.” But for me, it felt, in retrospect, like a very long time. I wanted to get that feeling across in the book, and I wanted to show how there were multiple factors that led to my enrollment in Love in Action. Each of those factors was highlighted in the different memoiristic sections. Each of them was also answering the LIA sections. One involved the Moral Inventory, where you have to account for every sexual thing that’s happened to you. But there’s one sexual thing that happened to me that was the most important, and that’s being raped in college, so that experience answered that section. Each section answered another reason why I was there. And each activity was a trigger for a lot of things that caused me to be there. I wanted to get that sort of feeling of just how draining it was to be there every day. It was just two weeks for me, but it was my whole life leading up to that moment.

The structure keeps the book from falling into sentiment or sensationalism. The language never gets preachy or judges the people who hurt you. How did you maintain that control while you were writing it?

That was really hard to do. I wanted to write fiction first, but this was the story that I now know had to be told in order for me to move on. When I decided to write the memoir, I was very conscious of the fact that I didn’t want it to be a trauma narrative. I didn’t want it to be a tell-all or an exposé, and I definitely didn’t want it to be a how-to guide or a survival guide of some sort. If it functions as any of those things, I would love it too, but the primary drive that I had while writing it was to borrow the fictional elements that I love. I don’t like things that preach at me, I don’t like things that create two-dimensional characters, I don’t like things that are pedantic, unless they’re interestingly pedantic. I felt like the best thing I could do was to humanize everyone and just make it as complicated as possible so that it would be talked about in a sophisticated way, hopefully. I didn’t want it to be simply a document of the time. I wanted it to be something that, ten years from now, we can still look at it and say, “That’s a really complicated piece of history that still applies in some way to people.”

Could you have imagined, even ten years ago, that there would be such a strong LGBTQ presence in literature, as there has been this year?

No, I mean Paul Lisicky’s memoir The Narrow Door, which is mind-blowingly good, talking about cruising in the first couple of chapters and then Garth [Greenwell’s novel What Belongs to You] is talking about picking up a prostitute, breaking a lot of ridiculous taboos that are still in mainstream gay culture. I think it’s really cool that at a time when we have marriage equality, we also have these more interesting queer narratives that are not necessarily mainstream. I feel like people at the end of the year are going to say, “It was the year of queer books. It was so gay!” Which would be great. This is the time where gay books can suddenly start to be marketable.

In the book and in interviews, you’ve discussed how the program groups things like pedophilia and bestiality together with being gay. So it’s stacked up next to each other as if it’s all the same thing.

I was very disturbed by that. I just remember thinking, I guess it’s the same. I was so stupid and naïve about it. I was like, “Well, I guess I don’t want to be a child molester so this is probably the right path for me.” Because it was so mixed up in my mind. That’s why I made it so particular with those chapters in between. In the chapter “Other Boys,” I really believed that because I was raped by a child molester, that that was some sort of rite of passage. I had always been told that gay men were predatory, and so I just believed. I thought, “Well, I guess that’s some sort of horrible continuum that I’m on and I don’t want that anymore.”

I remember in the 90s and even early 00s, the idea was still prevalent in popular culture and the media that gay sex equaled death. When you’re in this religious environment, it complicates it even further.

All the church members said, “First of all, you’re going to Hell. Secondly, you’re going to get AIDS, so it’s going to be painful, then you’re going to go to Hell.” We were on vacation one time, and we were at this restaurant, and this couple came in with their whole family. It was a gay couple, super sexy, beautiful men. One of the guys came up behind the other and started giving him a massage and my family lost it. They were like, “It’s disgusting,” whispering how they couldn’t eat, and how could people do that? And I remember looking at the couple and feeling both that they were the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen and also that they were the ugliest thing I had ever seen because they were just doing that. How dare they just do that in this world that doesn’t let me do that? It’s disgusting.

If you could talk to a young person now dealing with what you dealt with back then, or someone in a similarly repressive environment, or even yourself at that age, what would you say to them?

Don’t for a second believe that doubt is your enemy. Doubt is something that, throughout the Bible, has been an important tool for many people. Consider the fact that doubt might be the thing that will save you and will make your life richer in the future. Just because everyone tells you that you should be certain about who you are right now, doesn’t make it true, and you know that because you’ve already doubted almost everything so far. When I was growing up, there was tons of doubt, and it was interesting and confusing and messy, but there were all these mechanisms for ignoring it, and then suddenly there comes a moment, if you’re lucky, where you start to think, Wait, that history of doubt that I had was as real as my faith, and so which one is truer? As long as you have that doubt there, they haven’t taken away your soul, they haven’t succeeded at soul-murder. I would say, look at all these people in the Bible that doubted, and start there, and move out from there.