Appreciations: Lilith Latini’s “Wolves” and Rickey Laurentiis’ “You Are Not Christ”

Author: Thomas March

December 29, 2015

Every month, “Appreciations” looks closely at a selection of excellent poems from recently-published books by LGBTQ poets. Each column celebrates new work by appreciating some of the figurative and formal achievements of these poems.

This month, the inaugural installment of “Appreciations” celebrates two poems, Lilith Latini’s “Wolves” and Rickey Laurentiis’ “You Are Not Christ.” These two differently-intimate poems share a life-affirming combination of vulnerability and defiance, of resilience and will. And perhaps that is some small part of what has made them seem so vital, just now, in this time of long nights, lingering darknesses, and often-mystifying joy. Keep moving, each demands at some point, to know the power and reach of your body—know that you are alive.

“Wolves”

Behind the serrated leaves hide

a blackberry cane’s heaviest

globules of fruit.Behind that dense cluster

of laden canes are

his fingers, my grip,

his pulse, my thighs.Muzzles off, pants around

our ankles and the briefest

moment of sincerity amidst

the distending dusk.I didn’t need him to stay.

The quick night takes me

when he leaves, the cool

night takes my hand.All the darlings beyond the shadowed

tree line, gnashing their teeth. We run.

In Lilith Latini’s “Wolves,” a brief and furtive assignation in the woods becomes an opportunity to reflect on both the necessity and the limits of our most primal urges. The poem is at first only coyly suggestive in its sexuality. We are voyeurs from the first word of the first line, peering “behind” the blackberry bush’s foliage to find the “globules of fruit” that “hide” there. They are the “heaviest,” ripe and ready in all of their roundness—ready to be discovered, enjoyed. And then the second verse paragraph begins with an emphatic anaphora that reinforces the sense of peering discovery and the ready richness of what is sought “[b]ehind that dense cluster/ of laden canes.” It is an uncovering even more surprising in the enjambment between the fifth and six lines, where the plural verb “are” prolongs an anticipation of further uncovering. Here are no blackberries at all, but “his fingers, my grip” and “his pulse, my thighs.” The parallel structure of the lines underscores the mutual responsiveness of this hunger, as each of “his” parts becomes magnified in the speaker’s own physical response—clutching, containing, surrounding.

The next verse paragraph reveals the vulnerability and the tentativeness of this connection. With “[m]uzzles off”, they are metaphorically unrestrained—in this first suggestion that the “wolves” of the title can just as readily refer to the lovers themselves as to any other wolves that might appear. They embrace something primal in themselves; but with their “pants around/[their] ankles,” they are not fully naked, not fully vulnerable. They are ready to return to the time from which this “moment” was stolen. And yet, even in the ambivalence of its surrender, it is a “moment of sincerity”—but whose for whom? Truth and earnestness both reside in that word, a gentle word for what seems like a quick, hungry release. The incompleteness, the disconnection residing in their connection, is manifested, too, in the fact that the sentence is a fragment—with no subject, no verb, just the stark facts of what has been. And what it has been has not been nothing. It all happens against the backdrop of “distending dusk,” a softly alliterative phrase that brings yet more attention to the nature of this satisfaction—something both too full and too empty: and growing.

None of this, though, is dissatisfying. “I didn’t need him to stay,” the speaker declares, to begin the next paragraph. This is not the same as not wanting him to. Replacing one coupling with another, it is the “quick night” that “takes” her —suggesting among the many senses of “quick”, both readiness and vitality. This new coupling happens, as soon as the other lover is gone: “when he leaves, the cool.” And before the full sense of the sentence emerges in the next line, “the cool” is, for a moment, available to signify the calm and cold opposite of passion that replaces one lover’s presence with emptiness, here personified. But it is not just the condition of coolness but “the cool/night” that now, more tenderly, “takes [her] hand.”

As the poem closes, the speaker is alone with the cold but gentle night itself, but what is next? Who are these “darlings” “gnashing their teeth” in anticipation, in the shadows, as if they’d been there watching all along? Are these the literal wolves referred to in the title, or, more metaphorically, a world of other potential lovers with their demands? The gnashing of teeth suggests frustrated desire and readiness, all at once. And in response, the poem ends with the simple declaration, “We run.” And “we” is she and those “darlings,” she and the night, either running away or running toward, either chased or chasing—invigorated.

“Wolves” is from Improvise, Girl, Improvise

By Lilith Latini

Heliotrope, an imprint of Topside Press

Paperback, 978162729012, 56 pp.

June 2015

“You Are Not Christ”

For the drowning, yes, there is always panic.

Or peace. Your body behaving finally by instinct

alone. Crossing out wonder. Crossing out

a need to know. You only feel you need to live.

That you deserve it. Even here. Even as your chest

fills with a strange new air, you will not ask

what this means. Like prey caught in the wolf’s teeth,

but you are not the lamb. You are what’s in the lamb

that keeps it kicking. Let it.

Begin with the title. Is it just a declaration, or is it an admonishment? Is it motivated by despair or by acceptance? As the poem opens, the title seems merely obvious—there is no Christ-like walking on water here, only drowning. The emphatic “yes” reinforces the certainties of that first line, nestled as it is between two caesurae that halt the poem in that affirmation before it’s fully begun. Positioned as it is, “yes” can modify the drowning themselves, or the fact of panic’s omnipresence. Immediately though, as the next line begins, comes the just-as-certain fact of panic’s companion emotion: “Or peace.” If panic is “always”, then such peace is not an alternative, but an alternate, experience—existing in tandem and tension with frenzy.

A gentle release follows, a reversion to “instinct/alone,” with the enjambed line allowing the word “alone” to re-assert the singular intensity of instinct while also gesturing, especially with the full stop that follows, toward the situation’s essential solitude. This embrace of instinct appears at first to require a process of relinquishing: “Crossing out wonder. Crossing out/a need to know.” The imperative of release, erasure, manifests in the anaphora in “crossing out” and in the enjambment of these lines, which allows the second appearance of “crossing out” to be both a reinforcement of the first, and the beginning of its own new thought. To lose “wonder” and the “need to know” is to abandon imagination and curiosity, a kind of yearning that can only be a distraction at the threshold of death.

A gentle release follows, a reversion to “instinct/alone,” with the enjambed line allowing the word “alone” to re-assert the singular intensity of instinct while also gesturing, especially with the full stop that follows, toward the situation’s essential solitude. This embrace of instinct appears at first to require a process of relinquishing: “Crossing out wonder. Crossing out/a need to know.” The imperative of release, erasure, manifests in the anaphora in “crossing out” and in the enjambment of these lines, which allows the second appearance of “crossing out” to be both a reinforcement of the first, and the beginning of its own new thought. To lose “wonder” and the “need to know” is to abandon imagination and curiosity, a kind of yearning that can only be a distraction at the threshold of death.

But after imagination and curiosity have vanished, it is not quiet acceptance but urgency that remains: “You only feel you need to live.” Note, though, the placement of the modifier, “only,” before “feel,” rather than after it, so that the grammatical sense of the phrase is that the need to live is merely a feeling, not a reality. Yet the broader sense of the line still suggests that this “need to live” is the only thing possible to feel. The clipped clarity of the statements that follow urge this feeling into fuller force. Living is “deserved,” “even here,” as it begins to end. Even as the drowning lungs yield to the “strange new air,” presumably the invading water, this urge to live must override even empirical sense. If “you will not ask/what this means,” then the inevitable answer—death’s inevitability—cannot occur to you, and neither can the appeal of a peace that would resolve the panic of struggle in one, final, fatal direction.

This poem that begins by asserting what you are not, ends by telling you what you are. The simile likening the drowning to captured “prey” exists only as long as it takes to deny it in the next line: “you are not the lamb.” Your submission is not meek, nor it is a submission to death but to the destiny of unyielding struggle. Not the lamb, “[y]ou are what’s in the lamb/that keeps it kicking.” Naming this quality only as “what’s in the lamb” makes it seem more essential somehow, as intrinsic as it is ineffable. It is the irrepressible will to live—the “instinct” alluded to in the poem’s second line. The “peace” that opposes “panic” earlier in the poem has never been the peace of surrender to death. It comes of yielding to a will that demands to be channeled to the farthest extents of the limbs. The punctuating sentence, “Let it,” simultaneously commands, pleads, and prays that this be the only yielding, no matter the inevitable end.

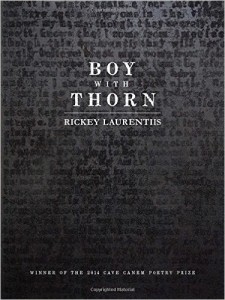

“You Are Not Christ” is from Boy with Thorn

By Rickey Laurentiis

University of Pittsburgh Press

Paperback, 9780822963813, 140 pp.

September 2015

“You Are Not Christ” is from Boy with Thorn, by Rickey Laurentiis © 2015. All rights are controlled by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA 15260. Used by permission of the University of Pittsburgh Press.

“Wolves” is from Improvise, Girl, Improvise, by Lilith Latini © 2015. All rights are controlled by Heliotrope, an imprint of Topside Press, New York, NY. Used by permission of Heliotrope.