Revisiting an Underground Life: A Look at Gad Beck’s Life in Nazi Berlin

Author: James McDonald

January 27, 2014

An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin (University of Wisconsin Press, 2001) retells the unbelievable story of a boy who grew to adulthood in the very heart of Hitler’s Germany. Yet the title is a bit of a misnomer. The leader of a wide network of Jewish resistance within the city, at the center of a vast web of international humanitarian efforts, Gad Beck’s (1923 – 2012) illegal life was very different from that we know best: the Franks’.

The son of an Austrian Jewish father and a converted Protestant German mother, Beck’s childhood was a happy marriage of cultures. His Christian relatives (at least his aunts, uncles and grandparents) embraced their Jewish family with an almost zealous love. They learned to prepare the Passover Seder with meticulous attention to Kosher laws, they attended and participated in his 1936 Bar Mitzvah, and one uncle even reached out to the distant Austrian Jewish relations during the war. “My upbringing was marked by this unobtrusive, never explicitly uttered tolerance. Such a devoted, open, and serene form of Christian-Jewish ecumenism, full of good heartedness, could have forged new directions for Central European culture if Hitler had not destroyed it all.”

The account focuses on those years most affected by the rise of Nazism: from his childhood up to his twenties. At the age of nine, Beck was prohibited from standing with his fellow students during the morning salute to Hitler’s government. At ten, he wasn’t allowed to stand on the podium at a school race he won because he wasn’t Aryan. Through the innocent eyes of youth, the early psychological effects of such discrimination and segregation become apparent. Shut off from his German identity, Beck turned to the one he still had left – he embraced his Judaism with an enthusiasm that surprised and unsettled his family. He remembers overhearing his mother complain to her sister that when things were getting worse for Jews, her son chose to emphasize that stigmatized facet of his identity.

That love could keep a family together, even through the most horrific of circumstances, is not surprising. As successive anti-Jewish laws made things harder, Beck’s Christian relatives stepped in without so much as a word. From paying for food, to clothes, to his Bar Mitzvah ceremony, one uncle even set up a secret bunker should the Jewish relatives ever need to disappear. With Kristallnacht, the Christian side of his family came to fully understand the seriousness of the times, and their principle became “Don’t let the Jews down!” This assertion is most vividly recounted when Gad, his sister and father were interned in a holding station. For days, his mother, aunts and uncles – even one in full German uniform just returned from the front – joined crowds of other Christians shouting, demanding the return of their families. Even in the face of Nazi machine guns, they refused to abandon their loved ones.

Yet it is the altruism of strangers and acquaintances that Beck really focuses on. Of course, there were many eager to take advantage of the situation to extort money, property, or especially from Beck, sex. But it is the stories of people like Fräulein Schmidt that truly resonate. A middle-aged prostitute, when she learned that a list of illegal Jews and their addresses had fallen into Gestapo hands, she hopped onto her bicycle and spent hours cycling across the city, during a night of heavy Allied bombing, to warn them. Because of her heroic act of selflessness, all 36 Jews on the list survived.

In this highly personal account, the war serves as a backdrop for Beck’s sexual growth. Initially, the number of encounters he had, the willingness of adults to accept their sons’ homosexual intimacies, and Beck’s ability to find romance even in a Nazi holding cell is baffling. Yet with Beck’s characteristically frank insight, it becomes understandable. In the midst of discrimination and near debilitating uncertainty, parents, like all parents, “were happy when their children were doing well, when they weren’t lonely, when they seemed happy.” When talking about his most serious love during those years, he says that understanding the depth of the dangers that surrounded their every moment “brought out an overpowering feeling of attachment between us.”

More than filling a glaring hole in literature on Nazi persecution of homosexuals – an estimated 15,000 were sent to concentration camps with at least half perishing – this book provides a uniquely relatable recollection. Immensely readable, on one level it is merely the story of a boy, and an often-humorous story at that. As a child, he remembers how one neighbour would gush over him: “Each time, two humongous breasts entered my field of vision, darkened the sky, robbed me of my delight, the air to breath, the world. No wonder I never enjoyed any sort of desire whatsoever for female breasts.”

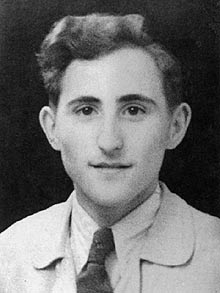

Yet he employs a remarkably effective rhetorical tool throughout. We all know what Nazi policies culminated in – the systematic murder of six million Jews, eleven million people in total – and Gad frequently juxtaposes known outcomes and future events with his present narration. When discussing his father’s forced labour on the railways he notes that “an efficient rail system was needed for the war (and not only for that).” When individuals only feature tangentially in the narrative, their fates are enumerated. Whether they ended up in Israel, or perished in Auschwitz, Beck grants a level of closure to the reader: there are no loose ends. Additionally, the inclusion of photographs serves as a reminder that these people truly lived. In this way, despite the disarming optimism Beck exudes, the reader can never escape the reality of the situation.

The scale of the Holocaust makes it difficult to properly come to terms with. The New York Times recently did a spotlight on the book, And Every Single One Was Someone, which attempts to convey the magnitude of loss by printing one word, “Jew”, six million times. In size 5.5 font, the word is repeated 4,800 times on each of the 1,250 pages. Yet when human devastation is in the millions, it’s easy for the numbers to become disassociated from the individuals whose lives are being totaled. Beck’s story, with the anecdotes he provides, illuminates the richness of life that was lost. It has been sixty-nine years since the liberation of Auschwitz, and Tel Aviv recently unveiled a memorial dedicated to those “persecuted by the Nazi regime for their sexual orientation and gender identity.” The importance of understanding the past, of never forgetting, is on vivid demonstration today. With anti-Semitism on the rise in Europe and the persecution of gays reaching new levels of state-backed support in Russia, Africa and the Middle East, it’s becoming more and more apparent how little effort people make to understand their neighbours.

An Underground Life provides a uniquely personal, highly entertaining, and disturbingly stark reminder of one of the most devastating of human atrocities. Through entering the mind of Gad Beck, however, the reader shares his distinctive outlook. Tears shed when reading this memoir do come from experiencing the depravity of human nature, but more often, they are inspired by the actions of those who risked everything to help their family, their friends, and even complete strangers. Beck’s optimistic view of people shines forth through the years of unparalleled evil. Acts of selfless courage gave Gad hope for a future – it inspired him to keep fighting against the seemingly insurmountable obstacle of blind hatred. His is a lesson that is as true today as it was nearly seventy years ago, and his message is one that needs to spread.

Photo via United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin

By Gad Beck

University of Wisconsin Press

Paperback, 99780299165000, 165 pp.

August 2000