Just As He Is: An Interview with E. Lynn Harris (1997)

Author: Keith Boykin

July 1, 2010

I first met E. Lynn Harris I had just moved to Washington in the winter of 1993 when I got a call from a writer with an unfamiliar name. Somehow, he had found a copy of an essay I had written for an unpublished anthology. He liked my essay and called to encourage me, indicating that his publisher, Doubleday, was interested. I confessed that I had not read, nor heard of, his new book, so he sent me a copy of his self-published Invisible Life and told me he had signed a contract with Doubleday to re-publish it with a broader distribution. Lynn was personally shy but professionally self-confident.

Having watched Lynn grow and develop as a writer and a person in the past few years has biased me in his favor. When I took his advice and contacted Doubleday about my own book, One More River to Cross: Black & Gay in America, Lynn championed my case When I began working at the National Black Lesbian and Gay Leadership Forum, he became one of the organization’s strongest financial contributors.

It is through this lens, therefore, that I see E. Lynn Harris, not only as a writer, but as a friend, supporter, and human being. Admittedly, I brought some of these biases to the table when we sat down on a Monday afternoon in September at a Washington hotel for this interview.

Keith Boykin: Reading your work, I’ve noticed things that struck me as being about you. You mention that one of your characters is reading Essence and Sister-2-Sister magazine; you mention attending the JFK party at the ’96 Democratic convention and you mention walking down Michigan Avenue near the Water Tower. When I hear these things, I’m hearing not just the character but I’m heating a little bit about you too. You live in Chicago, you read those magazines, you attended the JFK party. Is that what your books do?

E. Lynn Harris: Yes, I always give characters things that I’m familiar with; on a day-to-day basis when I’m writing.

KB: In some of the scenes from If This World Were Mine I was curious if some things didn’t come from your own life as well.

ELH: A lot of people would be surprised that there’s a lot of me in Dwight, more so than Leland.

KB: What about the “I hate white people” thing?

ELH: No, not that but I had to give him a major flaw, if you will, and that was it.

KB: A lot of the characters in your book seem somewhat materialistic. Even Dwight has $59,000 in savings and investments and is fairly well-off financially.

ELH: But he doesn’t flaunt it; he lives very frugally. I think that you find a lot of middle class blacks or people who moved up in the class structure tend to be frugal, to save, and then there are others who spend in the extreme. Even for myself, I think if I had been in the position that I’m in now years ago, I would have a lot more toys, you know, a lot more glamorous stuff, a big house, rolling driveway. But to me now, that stuffs not important; I’m very happy, I could probably own a million dollar house now, but I don’t see the need to do that. I want something I’m comfortable in. So I imagined Dwight as being frugal.

KB: Even so, I see some characteristics in him, like the fact that, in the scene when he looks down on his date because she orders Red Bull in a can and then he wonders whether he’s becoming too much of a Buppie, and of course there are so-called Buppie characters in all of your books, and I wonder…

ELH: I hate that term Buppie. I think my characters are people who are trying to live well. I don’t see them as being wealthy or anything like that, and it would be disingenuous to say that most people aren’t aspiring to do better in their lives, but we don’t know the financial problems that they’re having. It’s something that Terry MacMillan always brings up: why must we write a novel about the downtrodden? People want to read a novel to have some fun. Even though I do touch on issues that are sometimes tough to deal with, people basically want to see the characters living well. There are many black gay men who buy my books who are in the position that I was, five, six years ago in D.C., with very little money, and I plan to write about a character like that in the next book. I have friends who are having a tough time, trying to find their place within a class structure. They may have grown up in middle class homes, but now, because they’re pursuing something they love doing, they’re not able to live the way they may have lived.

KB: Some would say you’re glamorizing the “Buppie” lifestyle, others would say you’re satirizing it. Still others would say you’re just describing it.

ELH: I would say describing. One of the things that I was particularly careful of in this book is not referring to name brands. Every time that I would think about doing that, I would say well, what is it about Gucci or Versace that needs to be described. You can say “nice leather shoes,” indicating that they’re expensive. I don’t necessarily have to give it a name. Now, it almost makes me cringe I did it in Just As I Am and Invisible Life. Just too much detail. One of the things I think I’m successful at is knowing how much detail to give.

KB: Quite a few of your character descriptions are very color-conscious. You use everything from Hershey bar-colored to peanut-butter-brown skin to Sugar Baby-caramel color to honey-brown skin, oatmeal colored. Where’d you come up with these names?

ELH: Watching food; you notice, it’s always been about food, One of the things I think is wonderful about black people is we come in so many wonderful colors, and when I see a color that is any way past vanilla, its a potential way for me to describe it. Roderick brought home some Sugar Babies one day, and I said, oh, that’s a pretty brown. You’ll see men and women who are a beautiful brown, or just different hues. I’ve seen black people so dark that their skin just glistens; it’s so beautiful. So I use the different colors.

KB: How would you describe yourself?

ELH: Vanilla.

KB: Do you think that you’re helping to educate people about color-consciousness?

ELH: I hope so, because it’s still a problem within our community. A problem in the sense that people try to use it to divide us, just as they use sexuality, as a way of dividing.

KB: Is there any message being sent about the gay characters in your work?

ELH: I see the gay characters as multidimensional. If I only wrote about them being gay, and their sexual activities, that would be one-sided. It would be dreadful for me, as a gay man, to be writing things that only dealt with sex. tin this book, with Leland — what’s Leland’s issue? He’s out. He’s been gay all his life. He’s not hiding. So what’s gonna make him an interesting character? I know a lot of gay men have lost lovers and friends, and no one’s ever really dealt with that. And these are long-term relationships. I heard a straight man say that Leland and Donald seem like such a wonderful love story; they really love each other. That’s what I was trying to convey: that we love very hard, just like men and women do. And when we lose someone we love, be it through a break up, or be it through death, it’s very painful, and it takes its time to go on with our lives. People know how to handle a widow or widower when they’ve lost someone. But so many times now, when gay men are visible and out, when we’ve lost lovers and loved ones, no one really knows what to say m us, or how they can help us ease the loss.

KB: I wonder if you could talk about some of the humor in your books and how it’s used to deal with delicate issues. In If This World Were Mine, you write, “I’m beginning to feel like I will always be just one biscuit away from a permanent Jenny Craig membership.” At another point, a character says, “I’ve been gay since kitty was a cat.” And then in a third place in the book, a character says, “I invaded Monty like the Marines arriving on enemy territory.” Where do you come up with these things?

ELH: Oh, I don’t think of myself as funny. I’ve heard friends say that kitty is a cat thing. The weight thing is something that deep in my mind I always feel I battle with, and it’s amazing that I’m not anorexic. It’s funny, people will come up to me at signings, mostly women, and say, “oh you’re so much better looking than your picture.” I remember, in Brooklyn one afternoon, one lady came up to me and said, “oh you look great, lost some weight, makes you look younger.” And ten minutes later someone else said “oh, you must be doing all fight, you picked up a little weight.” (Laughter.) It’s always going to be a battle with me, even though I exercise every day. That’s where the biscuit line came up. The invading line had to do with how men sometimes make sex such a statement of anger with each other, and Basil was mad at Martin, and he wanted to show, you know, I’m in control, I’m the man, and that army reference is more of a macho thing. That’s the way Basil would think, not necessarily the way I would think.

KB: I would gather you’re probably the most popular black gay author.

ELH: Well, James Baldwin’s probably sold more books than me, and he was more of a personality.

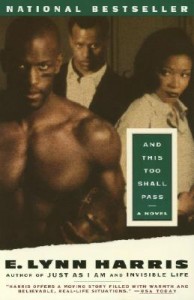

I think that if my career continues at its current pace, then that definitely will be true. Baldwin probably sold millions of books, and right now, I’m approaching my first million. Each book has done better. For instance, And This Too Shall Pass sold maybe 160 thousand in hardcover, and If This World Were Mine has already sold that many in six or seven weeks.

KB: You’re ahead of John Grisham…

ELH: But Grisham’s been out a while, so that’s not a fair comparison. Friends of mine always say, you’re over Grisham, and I let them enjoy that. (Laughter.) The whole charting thing, like the New York Times — now, that has made history in terms of how long I’ve been on there and how high I’ve gone. I wanted to go as high as #5 in the Times, I had prepared myself that I may not even be on the list for three or four weeks, which would have been okay, because you have Danielle Steele, you have Patricia Cornwell, this book Cold Mountain, Sidney Sheldon, Anne Rice — all these people have books coming out. So my agent, my publisher, and I knew that this would be a difficult time. So my goal was not to lower my expectation, to make the list again and to go higher than I did the last time.

KB: You’ve made #5.

ELH: Yes, the time before, I made six. I was ecstatic. This time I made the list a week after the book had been out. This week I dropped to seven, and I don’t like to say dropped, because that implies something bad is going on..And then last Wednesday I got the list, and I had been at seven, and I figured this time that I would probably drop another couple of notches. When I got the list, I looked from seven on down, and I didn’t see my name. So I just put it down, but I was kind of pissed off, so I grabbed the list again and looked up and saw I had moved up to four! This week I’ll be four! It was just crazy, because usually if you start down, you’re going to go on down, and to move from 7 to 4 was crazy, and so I topped my goal.

I always set goals for myself, and I want each book to do better. With this book I have been reaching a lot more fans. I’m seeing a lot more men. In this tour, I’ve had at least five women come up to me and say, my husband turned me on to you. It’s usually the other way around. I see the audience expanding, not only among women and African-American men, but white gay men — I’m seeing a lot more of them — and I’m seeing lot more heterosexual white women. I’ve gotten a couple of letters from white heterosexual women. One said she did not understand why, at the end of If This World Were Mine, she was crying. What she says, in the course of the letter, is it was about friendship. She ended the letter by saying, letters will be written, calls will be made, hugs will be given freely. And she says it’s all because of this wonderful book The only criticism, really, has been from quote unquote, black gay men. It hasn’t been rampant, but even if it’s one, it’s hurtful.

KB: What’s the criticism?

ELH. Too mainstream. That it seems that I’m just out to make money, or that I’ve reached so much widespread acclaim.

KB: How much pressure is fair to put on a writer to portray positive images of his community?

ELH: I think it’s very unfair. I think that writing is the one thing that people ought to be able to do as they’re moved to do. It would be disingenuous of me to ever write a novel that didn’t include black gay characters. I couldn’t do that. But by the same token, I can’t chronicle the whole history of black gay people in my fiction. I wrote Invisible Life because I wanted a story that I could identify with. Every story that I write is something that I would love to read, and I’m not out reading all of the gay fiction out there, partly because I’m interested in other things as well, and I want my novels reflective of that, so I think that it’s a lot to ask one person. But, I won’t be swayed, I will only write what’s in my heart. If I decide tomorrow to write an all-gay novel, that’s what I would do; not based on pressure from a community. If I decide I want to write a heterosexual novel, I would do that as well. A writer ought to be able to write different kinds of stories.

__

This interview was first published in the Lambda Book Report in 1997. Vol. 6, Iss. 5, p. 1