The Queer Desi Dilemma?

Author: Jihii Jolly

June 17, 2010

Within the South Asian community, there exist rigid culturally established dichotomies between male and female, older and younger, gay and straight, as well as dividing lines between social groups. Specifically in Indian society, it seems this history of social division has prompted a sort of black/white mentality; an inclination for constrained dialogue on taboo topics like homosexuality. Others are perceived as either gay or straight; you are in or you are out, never both.

This in-group/out-group mentality is being challenged, or at least brought to light, by emerging South Asian queer writers such as playwright Brenden Varma, Lambda Award winning author Rakesh Satyal, and musician turned author Vivek Shraya. While there are many areas to explore when it comes to homosexuality and Indian culture, one question is brewing: is there room for nuanced dialogue?

“Safe Space,” Varma’s 2004 piece published in the second volume of Catamaran, a magazine of South Asian American Writing, is a comical, sarcastic one-act play about a support group for gay South Asians. Varma implies that even within the South Asian gay community, one must subscribe to a sort of mainstream ideology on homosexuality. The protagonist, Vikram, a 27-year-old Hindu journalist of Gujarati decent, born and raised in the United States, rejects members of the support group on the pretext that he is unable (and perhaps unwilling) to relate to their other ethnic and religious identities. Vikram only wants to discuss the group’s “gay South Asian experience” in an isolated manner. To this and a series of other narrow-minded statements, he receives a retort from a feminist in the group and eventually, the unfruitful session dismantles and each character leaves with his or her array of overlapping identities in tow.

Perhaps the most striking bit of dialogue in the piece is Vikram’s shock at another gay South Asian man’s willingness to marry someone who is not a desi:

Doesn’t have to be South Asian? Are you serious? You would date a non-desi? What is wrong with you? Do you think just any white boy, or God forbid, any black boy, would ever be able to truly understand you? Raj, you are a gay South Asian. You have special needs.

Is Vikram to blame for his insular mentality? Though he whole-heartedly wishes to create a safe space for gay South Asians, he has been raised by a culture that demands particular behavior from its people. The relationship between parent and child requires a degree of filial piety; the role of man and woman in marriage is largely decided by custom. Individuality that results from blurred identity is still a new-fangled phenomena of the ‘Social Future,’ if you will, toward which great parts of South Asia are still carefully trotting at an unhurried pace.

In India, homosexuality was illegal until just last summer. The cultural shifts campaigned by liberal-minded youth will naturally take time to develop. Still today, many a dinnertime conversation tends to regard homosexuality as non-existent. A homosexual identity is ruthlessly unaccepted. On the other hand, some homosexual acts are accepted as religious or spiritual, provided that gay men or women adhere to the social requirement of heterosexual marriage and procreation.

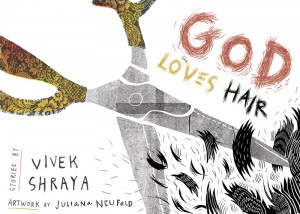

In his book God Loves Hair, Vivek Shraya seems to strengthen this point through his portrayal of an Indian child growing up in Canada. The isolated boy is unable, even unequipped, to create this forum of questioning within the privacy of his own mind. His confusion seems to be due to the fact that he is not encouraged to understand himself. The book offers a series of delightful vignettes told through the eyes of a young boy and his unabashed love for God, which carries him swiftly through each chapter until at one point, his heart is broken by God. In the chapter following this heartbreak, Shraya recounts an experience of “dirty thoughts,” an emotional and confusing portrayal of his protagonist’s encounter with a gay man. Ultimately however, his self liberation comes later in life, when he comes across a picture of a Hindu god represented as half male and half female.

He writes,

All the lines that divide what men and women should be and should do begin to blur in the light of this explicit fusion of two gods and two sexes. I breathe a sigh of relief. It is as though I have found an old picture of myself or the answer to a question I didn’t have the words to ask. I bring it home with me and tape it to my bedroom door as a declaration. I am not invisible anymore.

How ironic that the very gods who are blamed for the black/white austerity within Indian culture contain in themselves a forum for exploring blended identity. This phenomenon and these genuine “safe spaces” can only come about when cultures begin to fuse. This is the case of many emerging Indian-American and Indian-European writers, where on the basis of cultural migration identities are blending.

“The very nature of hinduism is inclusive and comprehensive in its approach to the human condition and to belief itself,” explains Rakesh Satyal. Blue Boy, his debut novel, won a Lambda Award earlier this year.

“It is somewhat ironic that many take limited views on the topic of self-identity, especially when it comes to gender, because so much about iconography in hinduism deals with the blending of identities, abilities, genders, strengths, and more,” he adds.

“That is very much what I was trying to explore in Blue Boy, in which the main character views Krishna very much as an embodiment of many gender identities, not just one.”

The story will come full circle when forums for whole-hearted dialogue find their footing in the further exploration of South Asian traditions. Brenden Varma appropriately ends his play with the words, “Where would desis be without their traditions?”

I’m hopeful about the emergence of a new dialogue with more openness for necessary nuanced debate and the acceptance of blended identities – a progressive dialogue that we will see more of through the courageous work of South Asian writers, which upholds the cultural vibrancy of South Asia yet simultaneously contributes a fresh perspective.

——

Illustration by Juliana Neufeld from the story “Eyebrows” in God Loves Hair.